On your table at Rico Food when you sit down, house-made nibbles to open your appetite: sweetly pickled crunchy

carrots and cucumbers.

If you regularly read this website, you already know that Mexico Cooks! is always on the lookout for a really good Chinese restaurant in Mexico City. In March 2012, you read our report about the wonders of Restaurante Dalián. Dalián, whose owners hail from Beijing, features very satisfying food from mainland China.

A few months ago, friends mentioned a Chinese restaurant in their neighborhood. Our friends didn't know the restaurant's name, they weren't sure of the exact address, and they had never eaten there. But they said it must be good, because it was always packed with Asian people. And they said the restaurant was on Av. Coyoacán, not far from their home in Colonia Del Valle. A few days later, we took our car for its monthly outing and drove down Av. Coyoacán: there it is! Sure enough, Restaurante Rico Food was just half a block from División del Norte and mere minutes from our home.

Julio Lai, the delightful owner and culinary inspiration at Restaurante Rico Food. He was brought from Taiwan to cook in a restaurant in the city of Guanajuato, Mexico. Several years later, he went back to Taiwan with the intent to open his own restaurant in his home country. Once he realized how difficult his hometown competition would be, he came back to Mexico City to open Rico Food.

At Rico Food, dry-fried green beans with pork and chile are so delicious and everyone loves them so much that, depending on how many diners we have with us, we sometimes have to order two big platefuls. At this meal, we all dove into the green beans so fast that they almost disappeared before I got a photo.

The last time we visited Rico Food, this order of 20 freshly steamed pork dumplings served our table of five remarkably restrained eaters. Of course we also ordered several other dishes. The dumpling's dipping sauce is prepared prior to being brought to your table; it's the perfect flavor combination of soy sauce, ginger, black vinegar, and sesame oil.

Fileted delicate white fish, bean sprouts, scallions, and hot red chiles are the heart of this incredibly delicious Taiwanese dish. When I saw the oily liquid in the bowl, I thought I might not care for this. Boy, was I wrong!

Up until now, Mexico Cooks! has been fairly unfamiliar with even the most common specialities from Taiwan. This Taiwanese pork chop is a staple recipe from any restaurant or home menu. Given that these pork chops are relatively easy to make, you might want to try them at home. This recipe (courtesy of Allrecipes.com) will give you chops similar to the ones that Rico Food serves.

Taiwanese Pork Chops

Ingredients

- 4 (3/4 inch) thick bone-in pork chops

- 2 tablespoons soy sauce

- 1 tablespoon minced garlic

- 1 tablespoon sugar

- 1/2 tablespoon white wine

- 1/2 tablespoon Chinese five-spice powder

- vegetable oil

- vegetable oil for frying

Directions

-

With a sharp knife, make several small slits near

the edges of the pork chops to keep them from curling when fried. -

Into a large resealable plastic bag, add the soy

sauce, garlic, sugar, white wine, and five-spice powder. Place chops

into the bag, and close the seal tightly. Carefully massage the marinade

into chops, coating well. Refrigerate at least 1 hour, turning the bag

over every so often. -

In a large skillet, heat enough vegetable oil to

fill the skillet to a depth of about 1/2 inch. Remove chops from

resealable bag without wiping off marinade. Lightly sprinkle cornstarch

on both sides of the chops. - Carefully add chops to skillet; cook, turning once, until golden brown on both sides and cooked through.

Serves four.

Steamed white rice with special Taiwanese sauce accompanied our meal.

Our comida (Mexico's main meal of the day) a few weeks ago at Rico Food celebrated the birthday of one of our group and offered her and two of our other companions their first taste of the restaurant's wonderful dishes. Our friends Alejandro and Allyson recently returned from several years in China; owner Julio Lai was astonished to be able to speak to both of them in Mandarin Chinese. Long conversation, special off-menu treats, and an introduction to Julio's beautiful wife ensued. Alejandro helped me talk with Julio, who promptly adopted me as his 'mamá mexicana' I'm proud to say that my new son is an altogether superlative cook!

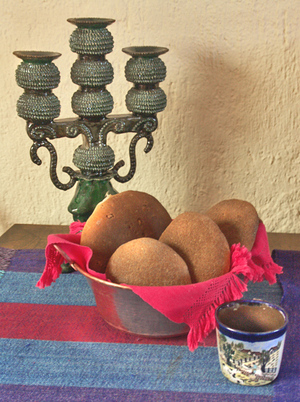

Last but very definitely not least, our dessert left all of us tremendously satisfied. Steamed sweet black sesame paste buns were the perfect ending, the final touch to a magical meal.

Exterior of Rico Food, Colonia Del Valle, Mexico City. The signage says

that Rico Food is a Chinese restaurant, but many of the specialties are

from Taiwan. Photo courtesy Alejandro Linares García.

Restaurante Rico Food

Av. Coyoacán 426

Col. Del Valle

Del. Benito Juárez

Mexico City

Tel. 5682-9220 or 5682-9989

Monday through Sunday, Noon until 10PM

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.