Decorating the church with compostura, as this type streamer is known in this part of rural Jalisco.

On the Catholic feast day of Saint Luke I invited my friend Julia to drive to San Lucas Evangelista with me to meet the coheteros (fireworks makers). It was the final day of the fiestas patronales (patron saint's festivities) for Saint Luke and I figured his little namesake town would be in full party mode.

We drove along the main street of the tiny town looking for the church. Usually a village church is easy to locate—I just look for the church torre (tower, or steeple) and point the car in its direction. This town was different; we couldn't see a steeple. Finally I pulled to the side of a narrow street and asked an elderly shawl-wrapped woman how to get to the church.

"Ay señora," she sighed heavily, "No se puede." (You can't.)

I was momentarily puzzled, but then light dawned. "Because of the fiestas?"

"Yes, the whole street is blocked with the rides and booths. You need to go to the last street in town," she pointed, "and park your car there. Then you can walk." She shook her head, scandalized by the madness of the fiestas.

Chuckling, I followed her directions and parked the car almost directly in front of the church, but on the rocky unpaved side street rather than the main street. We walked a few meters to the churchyard and immediately saw that the castillo (the castle, a large set-piece fireworks display) was under construction. We also noticed that the church has no torre—no wonder we hadn't spotted it immediately from the edge of town.

As I approached a group of men working on part of the castillo, they stood up to greet us. "Buenas tardes, how can we help you?"

I explained that I was interested in talking to the boss about the fireworks and that I was going to write an article about the fireworks. The first young man laughed and pointed at a second young man crouched on the ground working. "Talk to him, he's the boss's son. He'll help you." Then he laughed even harder. The young man in question rolled his eyes and grimaced.

"My name is Gerardo Hernández Ortiz, and I'm not the boss's son. I'm just a helper here. You want to talk to the big boss—he's over there." He pointed at another man standing by the churchyard gate. "Wait here a minute, I'll go get him." He socked the first young man in the arm as he walked to the gate. I watched as he talked briefly with a man in a navy blue plaid shirt. He glanced toward me and nodded.

Very shortly that man came over and shook my hand. "I'm Manuel Zúñiga of Cohetería del Pueblo (Town Fireworks Makers). My worker said you wanted to talk with me?" I explained my interest again and he became very serious.

"You have to explain to your readers that my profession is not dangerous. The majority of accidents happen because of juguetería, the small 'toy' fireworks such as palomitas (poppers) and luces de Bengala (sparklers) used by children. Those fireworks are imported from China and are much less stable than the ones we make here in Mexico. Those are very dangerous, very. Not these.

"Yes, there have been some bad accidents with our kind of fireworks, like the one in Veracruz in January 2003 (28 people were killed and more than 50 were injured when illegally stored fireworks exploded in a central market), but those incidents are very unusual.

"Our philosophy is that one person dies, but others follow in his footsteps and the work carries on and becomes better.

"My family has been making castillos, cohetes (rockets), bombas (bombs) and other fireworks for three generations. My grandfather, may he rest in peace, started making fireworks in San Juan Evangelista, the next town over there," he gestured to a spot in the distance beyond the church, "and then the whole family moved to Cuexcomatitlán, just up the road from here, and we've lived there ever since."

"It's always been a family business. You might say that we're Zúñiga and Sons." He smiled broadly and repeated, "I'm Manuel Zúñiga, at your service. We make a unique style of fireworks and we're very good at it. We've won many contests, including first place in the State of Jalisco. We've been asked to be judges at a pyrotechnics contest in the State of Mexico.

Twisting the carrizo (bamboo) into place.

"Most people think that the Chinese are the kings of gunpowder, that China is the world capital of fireworks. We've found out that the tradition of fireworks is very strong in England and that the English are really more knowledgeable than the Chinese. Their designs and innovations are at the forefront. We hope to travel to England one day to see their work in person."

I was fascinated with the construction of the various parts of the castillo. "It looks as if you have to be an engineer to figure out how this entire thing fits together and works," I said, reaching up to move several parts of the mechanism.

Bamboo tubes filled with gunpowder and wrapped with paper. The tubes are color-coded to indicate the effects they will have on the design.

"Yes, it's very complicated. Every tube that you see attached to the structure is filled with gunpowder and the chemicals that create the colors of the designs. We use several different kinds of materials to make the framework, like carrizo (bamboo canes) and madera de pino (pine wood). The bamboo is very flexible, the pine is rigid. There are other kinds of wood that we use to give more shape to the designs. Some of the sections of the castillo are hinged so that they move up and down as they spin.

"Designs are made with long thin tubes filled with gunpowder and with the thicker tubes that shoot fire. You might see flowers, a heart, a horse or a cow, or some religious symbols." He walked over to a large section of castillo lying on the ground and traced the outline of the design with his finger. "This one is a chalice with the communion host above it. Can you see it?" I certainly could. "It will look beautiful when it's lit up tonight."

"When it's time to put the whole castillo together, the parts are set onto a pole. We start with the topmost part and then use a system of pulleys to raise it up. Then we add the middle section, and then the bottom part under that."

"Come with me, I want to show you some other things." As we walked to the fireworks-filled storeroom next to the church, Sr. Zúñiga continued explaining the intricacies of his family business.

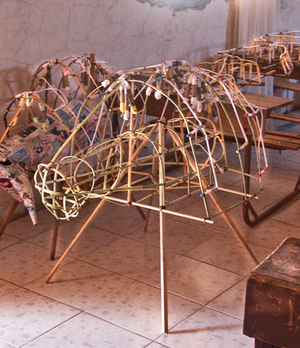

The torito (little bull) covered with fireworks. It is made to be carried and to chase happy fiesta-goers through the streets.

"Here, this is something different. It's a torito, a little bull. See the shape? Late tonight, we'll bring these out to play." He laughed. "A boy carries this little bull over his head—yes, after it's lit and while it's exploding with color and fire—and runs through the crowd. He'll chase whoever looks like a good victim. He hunts for whoever looks nervous. This torito has buscapíes fastened to it. Those are a kind of fireworks that shoots off the framework of the little bull and skitters along the ground. It literally means 'looks for feet'. It's only a little dangerous." He grinned and winked.

I grinned too, remembering a fiesta night in Guadalajara when a small boy with a blazing torito chased me down a cobblestone street as the festive crowd laughed to see the señora americana running to escape. And I remembered another night at the Basílica of Our Lady of Zapopan, when a buscapíes got under the long brown habit of a Franciscan priest. Fortunately he was a good friend, not to mention a good sport. Watching him dance to escape the buscapíes was the highlight of the festival for me.

Sr. Zúñiga talked as we walked back through the churchyard. "We work all year round. There are 25 of us who build the fireworks.

"We'll be in Ixtlahuacán de los Membrillos on October 21 for a visit of Our Lady of Zapopan and in Ajijic on October 31 for the last day of the month-long celebration for Our Lady of the Rosary. There will be a castillo in each town. Of course we've already started preparations for the nine-day festivities in Ajijic at the end of November."

We gazed up at the castillo being mounted just outside the cemetery fence. Curious, Julia asked him, "What does it cost to have one of these built?"

"The simplest ones start at $7,500 pesos—about $665 U.S.. The price goes up from that to about $20,000 pesos—about $1,800 U.S.—for more complicated castillos built on a central pole, like this one. Then there is another category of castillo, much more complex, that starts at $25,000 pesos. For that kind, the sky's the limit." He shook my hand. "Can't you stay until we burn this one at around eleven o'clock tonight?"

"I wish I could—maybe next year." With a last look at the work in progress, Julia and I headed for the car. I knew I'd dream of castillos that night. The sky was the limit.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.

Mexico Cooks! is traveling. We'll be back to our regularly scheduled programming in mid-July.