Two trivets and a large olla de cobre con asa (copper kitchen pot with a handle), all hand-hammered in the French style by James Metcalf, catch the afternoon sun at the Metcalf/Pellicer home in Santa Clara del Cobre.

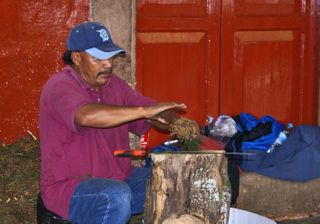

James Metcalf and Ana Pellicer, both important sculptors, choose not to live in Paris (where James worked early in his life, cheek by jowl with Constantin Brancusi, Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, René Magritte, and other seminal modern artists), New York (where both have exhibited their work in stellar galleries and museums), or Mexico City (where Mexico's hippest and most active artist's circle burgeons). Instead, the Metcalf/Pellicer household has built a better mousetrap in Santa Clara del Cobre, Michoacán. The world beats a path to their door in the heart of this tiny community of artisans.

One of Metcalf's small copper pots. Ana Pellicer told me, "We use this one every day, to heat the milk." He created an entire baterie de cuisine (set of cooking pots) for their personal use.

In 1950, James went to Majorca, where he studied ancient Mediterranean metallurgy and created the illustrations for poet Robert Graves' Adam's Rib. In the mid-1960s, James left Paris for Mexico, where he had heard that pre-Hispanic coppersmithing techniques were still in use. Told that what he searched for only existed in Santa Clara del Cobre, Michoacán, he set off to investigate. By the late 1960s, James Metcalf and Ana Pellicer, his former student, were living and working in Santa Clara.

Their early explorations were related to el cazo de Don Vasco, the 16th Century cooking kettle introduced to Santa Clara del Cobre by Don Vasco de Quiroga. The copper cazo, which ranges from stove-top size to immense (large enough to cook an entire cut-into-chunks pig) is still used wherever carnitas or candy are made in Mexico. It's safe to say that all of Mexico's copper cazos come from Santa Clara.

This hammered copper cazo has a diameter at the top of approximately 60 centimeters (two feet).

When James Metcalf arrived, Santa Clara del Cobre offered no luxury to the artist accustomed to life in Paris, New York, and other cosmopolitan centers. Houses in the town were little more than hovels. There was no indoor plumbing. Although nearly every man in town worked copper as a livelihood, with few exceptions the only items produced in the talleres (workshops) were cazos. All of the cazos were formed with a thin edge which was rolled around an iron wire to finish the piece. Metcalf, using clay pots from the nearby state of Colima as examples of shapes, taught the Santa Clara smiths the design and construction technique of the thick edge.

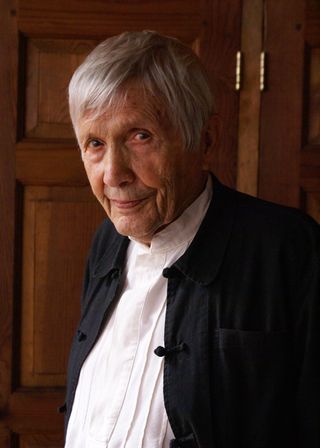

James Metcalf, extraordinary Renaissance man–elegantly knowledgeable, elegant as well in speech, dress, and manner. His work, sometimes classified as both surrealist and abstract expressionist, is an important force in 20th Century metal sculpture.

A few of the hundreds of tools in James Metcalf's work room. He crafted many of his own tools to accomplish the techniques of particular works. Until Metcalf's arrival, the coppersmiths of Santa Clara del Cobre had never seen the highly polished hammers commonly used in urban metalsmithing.

Metcalf's thick edge copper technique, completely different from the techniques used at the time in Santa Clara, revolutionized Santa Clara's artisanal copper production. The smiths slowly began to produce hollow ware other than cazos, including jugs, kitchenware, and other decorative work.

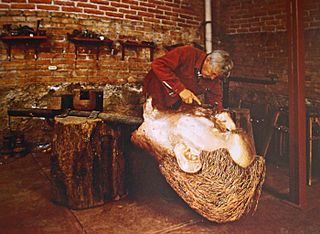

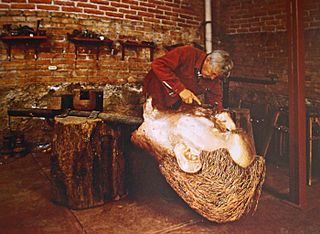

James Metcalf puts the final touches on his huge sculptural portrait of Mexican president (1934-1940) General. Lázaro Cárdenas Ríos. In 1985, Metcalf donated the sculpture to the town of Santa Clara del Cobre. Photo by Miguel Bracho, courtesy of Artisans of the Future by Jorge Pellicer, SEP, 1996.

Metcalf and the artisan coppersmiths of Santa Clara del Cobre received the commission to create the Pebetero Olímpico (cauldron which holds the Olympic Flame for the duration of the games) for the Olympic Games to be held in Mexico in 1968. The enormous cauldron, adorned with repousée decoration of maíz (corn, representing the life force of Mexico), brought world-wide attention to the traditional artisans of Santa Clara and their work.

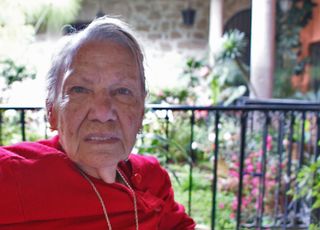

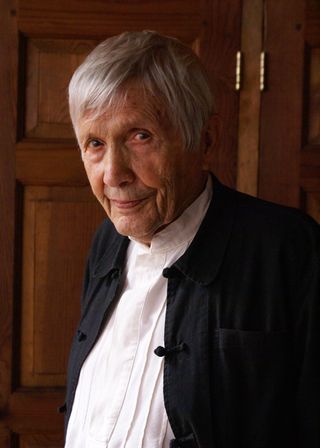

Ana Pellicer, August 5, 2009, at home in Santa Clara del Cobre. Exquisitely talented, Ms. Pellicer continues to create beautiful art. "What else can I do? Making art is my life, it's always my salvation."

Ana Pellicer arrived in Santa Clara del Cobre fresh from a privileged life in Mexico City and New York. Santa Clara, a community bound in rigid traditional gender roles and attitudes, did not respond well to her desire to work in copper. Talented, young and beautiful, her life in the small town was frequently difficult. Nevertheless, committed to the philosophy of 'mexicanidad'–the internalization of being Mexican in every aspect of life, including their art–both Pellicer and Metcalf felt deeply obligated to live and work in the Santa Clara community of artisans.

The maquette (small scale model) for La Máquina Enamorada (the Machine In Love), Ana Pellicer's enormous sculpture. The actual sculpture, commissioned by Mexican industrialist Francisco Trouyet, is now part of the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in Mexico City. La Máquina Enamorada weighs 250 kilos and measures nearly two meters high by nearly two meters wide and a meter and a half deep.

Over time, Pellicer to some degree gained the trust of the townspeople. In 1975, she and a group of artisan coppersmiths worked together to produce the commissioned piece La Máquina Enamorada (the Machine in Love). Enormous and enormously complex–made from nearly 300 kilos of solid copper ingot–the piece became the largest forged work ever made in Santa Clara and the first artisan-made work accepted by the Museum of Modern Art in Mexico City.

La Ulama or La Pelota que Rebota (The Ball that Bounces), by Ana Pellicer. The hammered copper decorative ring represents the cartwheel ruff, a heavily starched collar that was muy de la moda española (very stylish with the Spanish) during the time of the conquest of Nueva España. The black rubber ball represents the Purhépecha fire ball played in the pre-Hispanic game called Ulama. Pellicer collected the resin for the ball in the traditional method, from Michoacán pine trees. Exhibited in Denver, Colorado, as part of a complex installation, the piece represents ideas that transcend ancient times as traditions and native peoples bounce between cultures.

One of Ana Pellicer's lasting and tremendous accomplishments in Santa Clara has been incorporating women of the community into artisanal copper making. Despite intense opposition from many male artisans, Pellicer taught jewelry-making to some artisans' wives, who began to create jewelry that subsequently has won prizes at the community's annual copper fair.

El Beso (The Kiss), hand-hammered copper, 35X40X15 centimeters, Ana Pellicer, 1995. This hinged sculpture is currently part of the traveling exhibit The Women of Michoacán, Art and Artists. Photo courtesy Fred Derosset.

James Metcalf and Ana Pellicer founded several schools in Santa Clara del Cobre. In 1973, they received the support of the Ministry of Popular Culture and opened La Casa del Artesano. La Casa del Artesano offered artisan training to Santa Clara coppersmiths apart from the traditional training they received as apprentices in local talleres. Later in the 1970s, La Casa del Artesano closed.

Ana Pellicer's double copper plaques, each one smaller than a postcard, with male and female figures.

In 1976, Metcalf and Pellicer began teaching classes in their home. All the while, deep tensions continued to exist, not only within the artisans' community but also between ancient and modern techniques and styles of work, dress, jewelry, and, at its essence, community life.

Metcalf and Pellicer later founded, under the auspices of Mexico's Secretaría de Educación Pública (Secretary of Public Education) what became the most important school for artisans in Santa Clara del Cobre and arguably in all of Mexico: the Adolfo Best Maugard Center for Technical/Industrial Training #166 (Cecati #166). Teaching different techniques of metalsmithing and jewelry making at all levels of production, the school incorporated traditional and European forging methods, taught blacksmithing, casting in both lost wax and sand, machine tools, lathing, enamel work, stone cutting, and electroplating. All of those techniques opened multi-faceted new horizons of artistic and commercial opportunity to Santa Clara artisans.

In 2002, a Michoacán branch of Mexico's teachers' union took over directorship of the school, displacing Metcalf and Pellicer. The move was highly politicized and its consequences spilled over into extreme community tensions and division between the copper artisans and the former directors of the school. Many members of the artisan community continued (and continue until today) to consider Metcalf and Pellicer to be outsiders, even after their more than 35 years' involvement in the life of Santa Clara del Cobre. The pain and stress of this division are still abundantly apparent in both Metcalf and Pellicer's recounting of its incidents.

Sala (living room), Casa Metcalf/Pellicer, August 2009.

The lives and work of James Metcalf and Ana Pellicer are profoundly rooted in both art and artesanía, in both an international community of artists and a local community of artisans. Richly philosophical and deeply reflective, the artists confront their life's mixture of joy and pain in their work. Their story continues to unfold.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.