The Travel+Leisure Mexico public relations team emailed Mexico Cooks! not long ago with a surprise invitation to attend its 2011 Gourmet Awards. The awards event, which a restauranteur friend called 'the Oscars of Mexican restaurant cooking', were held at the elegant and posh St. Regis Hotel here in Mexico City. The gala event featured nominated chefs from every part of Mexico. Photo courtesy Brad A. Johnson.

To open the recent 2011 Travel+Leisure Gourmet Awards, the producers invited all of the restaurant chefs in the audience to go onstage for what Travel+Leisure called a historic group photograph. Most of the current luminaries of Mexico's traditional and modern restaurant heavens were present. Although the event was held in Mexico City, attendees and nominated chefs came from every corner of the country. All photos courtesy Quien.com except as noted.

Manuel Rivera, above, is the general director of Travel+Leisure's Grupo Expansión. He reflected, "Eleven years in the communications industry have been accompanied by a series of culinary experiences that have served to increase my curiosity about what constitutes good food. What I like best are surprises: an unexpected flavor or texture."

In the mind of Mexico's modern culinary world, there was only one place to be on the night of the awards: in the Diamond Salon at the St. Regis Hotel. High-voltage energy fueled the tension that accompanied the wait for the awards ceremony.

Sommelier Glo Lescieur of Grupo La Castellana, snapped during the party with Mexico Cooks!. Photo courtesy Vinus Tripudium.

Travel+Leisure created eleven separate gastronomic awards categories. They were:

- Chef Promesa (Up and Coming Chef)

- Mejor Restaurante Cocina Regional y Tradicional (Best Regional and Traditional Restaurant)

- Mejor Restaurante de Hotel (Best Hotel Restaurant)

- Mejor Entrada (Best Appetizer)

- Mejor Plato Fuerte (Best Main Dish)

- Mejor Postre (Best Dessert)

- Mejor Menú Degustación (Best Tasting Menu)

- Mejor Concepto (Best-Conceived Restaurant)

- Mejor Arte al Plato (Best Presentation)

- People's Choice

- Best of the Best

A panel of fifteen experts–whether by vocation or avocation–was assembled to judge the categories. The panel of judges included Nicolás Alvarado, Mariana Camacho, Roberto Gutiérrez Durán, Patricio Villalobos, and Manuel Rivera of Travel+Leisure Grupo Expansión; media commentators Marco Hernández, León Krauze, Carlos Loret de Mola, Nicolás Vale; and wine experts Hans Backoff, Jr., Pablo Baños, and Paulina Vélez, in addition to Rectora Esmeralda Chalita Kaim of the Colegio Superior de Gastronomía, among others.

Chef Paulina Abascal and Juan Luis Rodríguez entertained the crowd as they presented the coveted awards. First one and then the other read the list of nominees; then they alternately announced the winners. Applause, whistles, and shouts of congratulations filled the room as the presenters read each winner's name.

Winners:

- Chef Promesa: Chef José Manuel Baños, Restaurante Pitiona, Oaxaca

- Mejor restaurante regional: Chef Ricardo Muñoz Zurita, Azul y Oro, DF

- Mejor restaurante de hotel: Chef Alejandro Ruíz, Casa Oaxaca, Oaxaca

- Mejor entrada: Foie de Algodón, Chef Mikel Alonso, Biko, DF

- Mejor plato fuerte: Escolar Verde Apio, Chef Mikel Alonso, Biko, DF

- Mejor postre: Creme Brulée de Pera, Chef Sonia Arias, Jaso, DF

- Mejor menú degustación: Pujol, Chef Enrique Olvera, DF

- Mejor concepto: La Leche, Chef Alfonso Cadena, DF

- Mejor arte del plato: Oca, Chef Vicente Torres, DF

- People's Choice: Paxia, Chef Daniel Ovadía, DF

- Best of the Best: Pujol, Chef Enrique Olvera, DF

Chef Mikel Alonso, Restaurante Biko, and Chef Sonia Arias, Restaurante Jaso, show off their awards.

Chef Alejandro Ruíz, Restaurante Casa Oaxaca, receives his award from the lovely Travel+Leisure's ceremony assistant.

Chef Daniel Ovadía, Restaurante Paxia, rejoiced over the People's Choice award. Rather than rely on its panel of experts, the Travel+Leisure website offered its readers a one-week opportunity to vote for their favorite restaurant and pick the People's Choice winner.

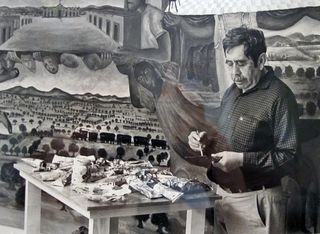

Chef Enrique Olvera and Restaurante Pujol received the Best of the Best "G" statuette, along with an original work created especially for the category by artist Manuel Monroy.

Chefs Gerarado Vázquez Lugo of Restaurante Nico's; Ricardo Muñoz Zurita of both Azul y Oro and Azul/Condesa; Carmen Titita Ramírez of El Bajío; Enrique Farjeat; Alicia Gironella d'Angeli of El Tajín, and Maritere Ramírez Degollado of Artesanos del Dulce celebrate at the cocktail reception following the awards ceremony. Photo courtesy Claudio Poblete.

Some of the eleven winners lined up for a photo: left to right, chefs Enrique Olvera, Daniel Ovadía, Sonia Arias, Ricardo Muñoz Zurita, Alfonso Cadena, José Manuel Baños, Alejandro Ruíz, and Mikel Alonso.

What can I say? It was a marvelous night, filled with stars and the chatter and gossip of a galaxy of friends. Some of the winners caused Mexico Cooks! to say, "Well, but of course!" and others were a big surprise. In saying thank you, every one of the winners echoed the thoughts of all of us watching: every restaurant depended on an entire team to achieve its success. No single chef won alone.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.

Disclaimer: Marca País-Imágen de México is a joint public and private sector initiative designed to help promote Mexico as a global business partner and an unrivaled tourist destination. This program is designed to shine a light on the Mexico that its people experience every day. Disclosure: I am being compensated for my work in creating content for the Mexico Today program. All stories, opinions, and passions for all things Mexico that I write on Mexico Cooks! are completely my own.