Part One of a three-part series of articles about Mexico Cooks!' explorations in the indigenous village of Zinacantán, Chiapas. All three articles were originally published in March, 2008. Enjoy!

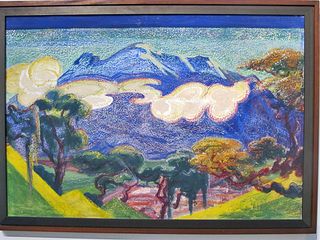

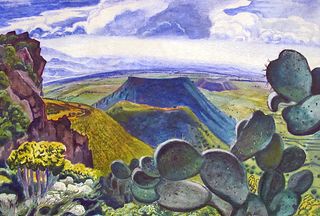

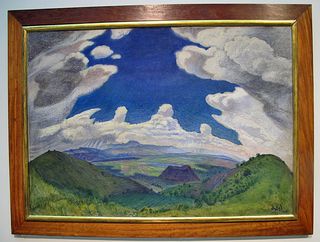

The highlands of Chiapas, the southernmost state in Mexico, are unlike any region of the 27 other Mexican states I know. The indigenous culture of the highlands is still fiercely Mayan, albeit with a veneer of Catholicism. The Chiapanecan Maya are for the most part unwelcoming to outsiders, holding their customs and celebrations close to their chests as jealously guarded secrets. Some regions forbid entry to both mestizos and foreigners, some forbid the taking of photographs, and some have essentially seceded from Mexico, allowing no access to services commonly accepted as essential everywhere else in the country.

There are a few small indigenous towns where outside visitors are at least superficially welcome, including the pueblo called San Lorenzo Zinacantán, located in a valley at 8500 feet above sea level, just six miles from the small but cosmopolitan city of San Cristóbal de las Casas. In Zinacantán, where the women dress like flocks of exotically beautiful bluebirds, a prominent sign on the church door reads, "Se prohibe matar pollos durante sus rezos," ('Killing chickens during your prayers is forbidden'), and the vernacular is Tzotzil, derived from Mayan. The name Zinacantán means "place of the bats". Mexico Cooks! missed seeing bats, but we lucked upon certain mystically Mayan Zinacantán ceremonies that left us wide-eyed and pensive.

Zinacantecas Juana Hernández de la Cruz, Josefa Victoria González, Juana Adriana Hernández Hernández, and Yolanda Julieta González Hernández laughed with delight when they saw their photographs.

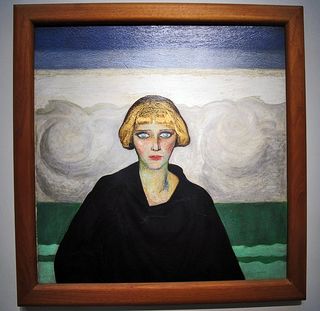

Village residents wear ropa típica (native dress) made by their own hands. Women use hand-woven long black wool skirts, hand-embroidered red or blue blouses embroidered in teal blue, deeper blue, and green thread, and stunning tassel-embellished shawls. It's possible to identify the families that men, boys, and young girls are from based on the style of weaving and embroidery in the garments their wives, mothers and aunts make for them.

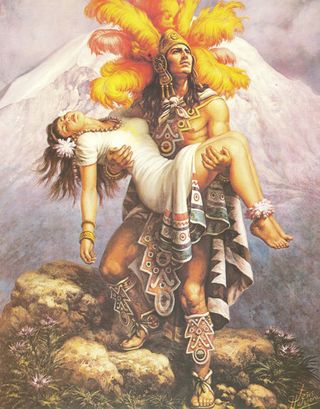

For their weddings, Zinacantán women wear the k'uk'umal chilil, an elaborately woven huipil (long blouse). White feathers are woven among the colored borders of these wedding dresses, which are nearly long enough to reach the ground. Under the huipil, the bride wears a finely hand woven and embroidered navy blue woolen skirt. The bride's white dress takes approximately five months to weave on a back strap loom. The people of Zinacantán say that the hen is a domestic animal that has feathers but cannot fly, walks on two legs just like people, is dependent on them for its nourishment, and is always near the house even when it runs loose. So the feathers that women weave into the bridal garment represent the attitude of the hen, which the bride is expected to adopt: she will not leave the household, even though she is capable of doing so, and she will shape a relationship of interdependence with her husband. Hence the feathers are a symbol of good marriage, as are the three borders of multicolored embroidery. In addition to the long blouse and the navy blue skirt, the bride wears a long white embroidered shawl which covers most of her head and face during the marriage ceremony.

For their weddings, Zinacantán women wear the k'uk'umal chilil, an elaborately woven huipil (long blouse). White feathers are woven among the colored borders of these wedding dresses, which are nearly long enough to reach the ground. Under the huipil, the bride wears a finely hand woven and embroidered navy blue woolen skirt. The bride's white dress takes approximately five months to weave on a back strap loom. The people of Zinacantán say that the hen is a domestic animal that has feathers but cannot fly, walks on two legs just like people, is dependent on them for its nourishment, and is always near the house even when it runs loose. So the feathers that women weave into the bridal garment represent the attitude of the hen, which the bride is expected to adopt: she will not leave the household, even though she is capable of doing so, and she will shape a relationship of interdependence with her husband. Hence the feathers are a symbol of good marriage, as are the three borders of multicolored embroidery. In addition to the long blouse and the navy blue skirt, the bride wears a long white embroidered shawl which covers most of her head and face during the marriage ceremony.

Zinacantán men wear short pants and a knee-length cotón (a sleeveless garment made of one piece of hand-woven fabric sewn up the sides to the armpits, with a cut-out for inserting the head). The cotón is fastened with a wide red cotton belt wrapped several times around the waist and knotted. Over that, a man wears a hand-woven and embroidered pink fabric vest with long, elaborate tassels. A large scarf wraps around the man's head, either with or without multi-colored ribbons trailing down his back, and over the scarf the men wear a handmade hat woven of palm fronds, long colorful ribbons cascading from the peak of the sombrero.

Because many people in Zinacantán are reluctant to have their pictures taken, I took the photo of traditional wedding clothing in a women's cooperative crafts store with the permission of the women in the second photograph, who staffed the store the day Mexico Cooks! visited.

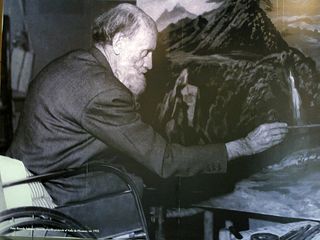

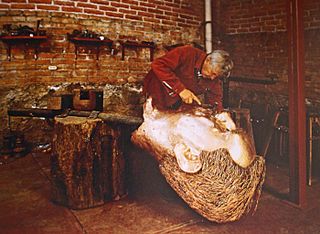

Sra. Pascuala Pérez Pérez weaves using a back strap loom.

The loom with a portion of Doña Pascuala's weaving lies neatly where she left it momentarily to tend the cooperative store.

Crafts work such as weaving traditional brides' huipiles, rugs, tablecloths, blouses, shawls, and straw hats has become the major source of income for many zinacantecos (residents of Zinacantán). Doña Pascuala told me, "We start as children, learning to separate the colored threads and put the same colors together. Many learn how to embroider, but the bad thing is that no one helps us export our crafts to anywhere outside the area."

Next week, read Part Two as Mexico Cooks! continues its visit to San Lorenzo Zinacantán, Chiapas.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.

Mexico Cooks! is traveling. We'll be back to our regularly scheduled programming in mid-July.