Carnicería (meat market), Mercado San Juan, Morelia, Michoacán. Would you consider this big pink pig head to be 'authentic' Mexican food? It truly is; every part of the head is used in Mexico for preparing one dish or another. Most commonly, the head is used for making pozole.

More and

more people who want to experience "real"Mexican food are asking about the

availability of authentic Mexican meals outside Mexico. Bloggers and posters on food-oriented websites have vociferously

definite opinions on what constitutes authenticity. Writers' claims range from the uninformed

(the fajitas at such-and-such a restaurant are totally authentic, just like in Mexico) to the ridiculous (Mexican cooks in Mexico can't get good ingredients, so

Mexican meals prepared in the United States are superior).

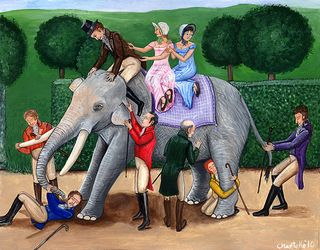

Much of

what I read about authentic Mexican cooking reminds me of that old story of the

blind men and the elephant. "Oh," says

the first, running his hands up and down the elephant's leg, "an elephant is

exactly like a tree." "Aha," says the

second, stroking the elephant's trunk, "the elephant is precisely like a

hose." And so forth. If you haven't experienced what most posters

persist in calling "authentic Mexican", then there's no way to compare any

restaurant in the United States with anything that is prepared or

served in Mexico. You're simply spinning your wheels.

The blind men and the elephant.

It's my

considered opinion that there is no such thing as one definition of authentic

Mexican. Wait, before you start

hopping up and down to refute that, consider that "authentic" is generally what

you were raised to appreciate. Your

mother's pot roast is authentic, but so is my mother's. Your aunt's tuna salad is the real deal, but

so is my aunt's, and they're not the least bit similar.

The

descriptor I've come to use for many dishes is 'traditional'. We can

even argue about that adjective, but it serves to describe the

traditional dish of–oh, say carne de

puerco en chile verde–as served in the North of Mexico, in the Central

Highlands, or in the Yucatán. There may

be big variations among the preparations of this dish, but each preparation is

traditional and each is authentic in its region.

I think

that in order to understand the cuisines of Mexico, we have to give up arguing about

authenticity and concentrate on the reality of certain dishes.

Traditional Mexican pork tacos al pastor (shepherd-style tacos) are a derivation of shawarma, traditional Middle Eastern spit-roasted lamb, chicken, or beef, imported to Mexico by Lebanese immigrants during the 19th century.

Traditional

Mexican cooking is not a hit-or-miss let's-make-something-for-dinner

proposition based on "let's see what we have in the despensa (pantry)." Traditional Mexican cooking is as complicated and precise as traditional

French cooking, with just as many hide-bound conventions as French cuisine imposes. You can't just throw some chiles and a glob of chocolate into a

sauce and call it mole. You can't simply decide to call something Mexican salsa when it's not. There are specific recipes to follow,

specific flavors and textures to expect, and specific results to attain. Yes, some liberties are taken, particularly

in Mexico's new alta

cocina (haute cuisine) and fusion

restaurants, but even those liberties are generally based on specific traditional recipes.

In recent

readings of food-oriented websites, I've noticed questions about what

ingredients are available in Mexico. The posts have gone on to ask

whether or not those ingredients are up to snuff when compared with what's

available in what the writer surmises to be more sophisticated food sources

such as the United States.

Frijoles peruanos (so-called Peruvian beans) heating in lard, almost ready to be mashed with a blackened chile serrano, resulting in Mexico's ubiquitous and iconic frijolitos refritos (well-fried beans).

Surprise,

surprise: most readily available fresh foods in Mexico's markets are even better than similar

ingredients you find outside Mexico. Foreign chefs who tour with me to visit Mexico's stunning produce markets are inevitably

astonished to see that what is grown for the ordinary home-cook user is

fresher, more flavorful, more attractive, and much less costly than similar ingredients

available in the United States.

It's the

same with most meats: pork and chicken are head and shoulders above what you

find in North of the Border meat markets. Fish and seafood are from-the-sea fresh and distributed every day, within just a

few hours of any of Mexico's coasts.

A traditional way to prepare and plate chiles poblano rellenos

(stuffed poblano chiles): a poblano chile, roasted, peeled, and seeded,

then stuffed with a melting white cheese. The chile is then dredged

with flour and covered with an egg batter and fried. It's served

floating in a pool of very light, mildly spicy caldillo (tomato broth).

Nevertheless,

Mexican restaurants in the United States make do with the less-than-superior

ingredients found outside Mexico. In fact, some downright delicious traditional Mexican meals can be had

in some North of the Border Mexican restaurants. Those restaurants are hard to find, though,

because in the States, most of what has come to be known as Mexican cooking is

actually Tex-Mex cooking. There's

nothing wrong with Tex-Mex cooking, nothing at all. It's just not traditional Mexican cooking. Tex-Mex is great food

from a particular region of the United States. Some of it is adapted from Mexican cooking and some is the invention of

early Texas settlers. Some innovations are adapted from

both of those points of origin. Fajitas, ubiquitous on Mexican

restaurant menus all over the United States, are a typical Tex-Mex

invention. Now available in Mexico's restaurants, fajitas are offered to the tourist trade as prototypically authentic.

You need to

know that the best of Mexico's cuisines is not found in

restaurants. It comes straight from

somebody's mama's kitchen. Clearly not

all Mexicans are good cooks, just as not all Chinese are good cooks, not all

Italians are good cooks, etc. But the

most traditional, the most (if you will) authentic Mexican meals are home

prepared.

The simple ingredients of caldo de pollo (Mexican chicken soup) may vary in one or two aspects from region to region, but the traditional basis is what you see: the freshest chicken, onion, carrots, chile, and cilantro give flavor to the broth.

That

reality is what made Diana Kennedy who she is today: for 50 years, she has taken the time to

travel Mexico, searching for the best of the best of the

traditional preparations. For the most

part, she didn't find them in fancy restaurants, homey comedores (small commercial dining rooms) or fondas

(tiny working-class restaurants). She found them as she stood next to

the stove in a home kitchen, watching Doña Fulana (Mrs. So-and-So) prepare comida (the midday main meal of the day) for her family. She took the time to educate her palate,

understand the ingredients, taste what was offered to her, and learn, learn,

learn from home cooks before she started putting traditional recipes,

techniques, and stories on paper. If we

take the time to prepare recipes from any of Ms. Kennedy's many cookbooks, we

too can experience her wealth of experience and can come to understand what

traditional Mexican cooking can be. Her books bring Mexico's kitchens to us when we're not able to go to Mexico.

Diana Kennedy at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma Mexicana, June 2011.

In order to understand the cuisines of Mexico, we need to experience

their riches. Until that

time, we can argue till the cows come home and you'll still be just another blind

guy patting the beast's side and exclaiming how the elephant is mighty like a

wall.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.