Ripe chirimoyas. Outside, the chirimoya skin is a dull green color. Inside, chirimoya flesh is creamy white; its seeds are large and black. The size can range from the diameter of a tennis ball to the size of your head. Photo courtesy Rawkyourhealth. All photos by Mexico Cooks! unless otherwise noted.

In Mexico, a first trip to a neighborhood tianguis can be mind-boggling—there are so many sights and smells of so many unfamiliar foods. For now, let's take a tour of some of the tropical fruits that you'll want to try.

I see so many marvelous tropical fruits on Tuesday at the tianguis (street market) where I usually shop: cherimoya, guanábana, mamey, and carambola (star fruit). There are stacks of papaya, mango, zapote (custard apple), maracuyá (passionfruit), and plátanos machos (bananas nearly the size of your forearm)—and other tiny bananas, the ones that are the size of your thumb.

Tunas (prickly pears). Since when is a tuna a fruit, not a fish?

The fruits available in season in Mexico can be confusing when we're used to the ordinary apples, peaches, oranges, pears and plums in North of the Border supermarkets. We have those "normal" fruits here too, but wait till you try the exotic produce that awaits you in Mexican markets.

The guanábana (soursop) can have a size range as wide as that of the chirimoya. Either fruit should be eaten when the fruit is very soft but not mushy. At home, I often cut a small ripe cherimoya in half and eat it with a spoon right from the skin. It makes a wonderful light dessert. The seeds are big, black, shiny, and easily discarded.

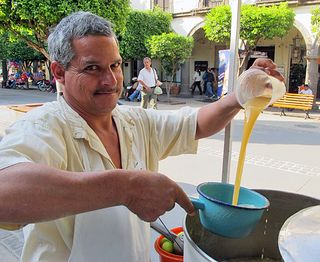

Guanábana flesh is eaten with a spoon or is used to make drinks and paletas (popsicles). Try this easy, delicious, and refreshing drink.

Agua Fresca de Guanábana

(Fresh Guanábana Juice Drink)

1 pound ripe guanábana

3/4 cup white sugar

8 cups water

1 cup milk (optional)

Cut the guanábana in half and scoop out the tender white flesh. Discard the bitter peel. Put the fruit flesh in a large bowl and reduce to a pulpy liquid, using a potato masher or the back of a large spoon. Discard the large black seeds as they appear.

When the fruit pulp is mostly liquefied, add the sugar and stir together with the fruit pulp and its juices. Put the fruit and sugar mixture in a 3-quart pitcher. Add the eight cups of water and the milk, if you wish. Stir well and chill for an hour or more.

The papaya and the mango are two of the more familiar tropical fruits available in Mexican shops and stalls.

The deep orange-red flesh of the Mexican papaya is much richer and sweeter than its small yellow Hawaiian relative. The papaya is best eaten when very ripe; the flavor and sweetness have developed beautifully just when you think the fruit might need to be thrown in the trash can.

When the papaya is super ripe—even a little moldy in spots—cut it in half and discard the seeds. Peel the papaya and cut away any small sections that might be overly soft (the overly ripe spots will be darker in color, translucent and softer than the rest of the fruit). It's delicious cut into chunks for breakfast, with a squeeze of limón criollo (the tiny round Mexican lime), a sprinkle of salt, and a dash of powdered chile if you like a little heat with your tropical fruit. For dinner, papaya slices combine with thinly sliced red onion, toasted pecans, and fresh watercress to make an exotic and refreshing salad. Try the salad with a raspberry vinaigrette dressing, either your own concoction or a bottled variety.

Mango petacón (very large mango, in this instance the variety is Hayden), Xochimilco, Mexico City.

There are nearly 2,000 varieties of mango grown worldwide. India produces more mangos than all other fruits produced in that country combined. The mango, king of fruits, is related—believe it or not—to poison ivy. Cultivated in Asia for more than 4,000 years, the growing of mangos has now spread to most parts of the tropical and sub-tropical world. The mango could well be the national fruit of Mexico.

A mango tree can grow 75 to 100 feet high and bears thousands of fruits each year. During mango season (June-August) here in the Guadalajara area, we use caution when walking under enormous mango trees; one of the heavy fruits could inflict a mighty thump to the top of an unsuspecting head.

Mangos are so wonderfully versatile that it's difficult to choose one particular mango recipe for you to try. Eaten fresh for breakfast, lunch, or dinner, the mango is unbeatable. One friend substitutes mango slices for fresh peaches when making cobbler, pie, or Brown Betty. Another makes a fantastic mango mousse, and yet another is renowned for her mango sorbet.

Cook's Tip:

Cutting up a mango can leave you with juice up to your elbows, stains on your clothing, and stringy shreds of fruit in your mixing bowl. Here's the simplest way to cut a mango with minimal mess, loss of fruit, and frustration. You'll be pleased that your mango, cut this way, will not be the least bit stringy.

Lay the mango on your cutting board with the narrowest side facing up. With a very sharp knife, cut completely through the mango along one side of the broad, flat seed. Then cut through the mango along the other side of the seed, leaving a narrow strip of skin and flesh around the perimeter of the seed. Set the seed portion aside.

Lay the two halves of the mango skin-side down on the cutting board. Cut through the mango flesh (but not through the skin) to make approximately nine diamond-shaped pieces in each mango half. Then gently flip each half of the mango inside out, so that the diamond-shaped pieces pop up. Use your knife to cut each piece free of the skin.

Next, cut the skin from the strip of mango surrounding the seed. Cut the flesh in pieces as large and as close to the seed as you can. Cut all the mango flesh into pieces the size you need.

Voilà, no strings, no shreds, and no lost juice.

My inviolable household rule is that the one who cuts up the mango gets to slurp any remaining fruit from the seed. Try to suck the seed until it's bone-white–that's how we do it in Mexico.

The banana is a familiar North of the Border favorite. Babies eat it as their first mashed fruit; older folks can eat one a day for an easy daily dose of potassium. Here in the subtropics, we have a huge variety of bananas that are just beginning to make their way north to Latin markets in the United States and Canada.

The guineo (similar to the ordinary banana), the dominico (a tiny banana also known as the ladyfinger), the manzano (the 'apple' banana), and the plátano macho (the 'macho' banana) are only four of the many types of this fruit that we see regularly in our markets.

The tiny ladyfinger banana, three to four inches long, is delicious eaten as a snack. The peel is almost paper-thin and the firm flesh is sweeter than most full-size bananas.

The manzano banana has reddish peel and a marked apple-banana flavor. These were for sale in the Mercado Medellín in Mexico City.

The plátano macho is my particular favorite, however. While it's still green and hard, it can be sliced, pounded thin, and fried into savory, salty chips called tostones. Fully ripened—the skin at this stage is dark brown or black—the plátano macho is called the maduro (mature or ripe). I don't get nervous even when I see that my maduros have a spot or two of mold on the skins. That's when they're the best, and this way to prepare them is my favorite. Be careful, they're addictive.

Plátanos machos, fried to a sweetly caramelized golden brown.

Plátanos Machos Fritos

Fried Sweet Plantains

2 very ripe plátanos machos (plantains)

vegetable oil

Peel the plaintains. Cut each plantain on the diagonal into pieces 1/4" thick.

Heat approximately 1/4" vegetable oil in a large non-stick or cast iron skillet. The oil should be quite hot but not smoking. If the oil starts to smoke, remove the skillet from the heat until the oil cools down slightly.

Put as many of the plaintain slices in the frying pan as will fit without touching one another. Fry on one side until golden brown. Flip each slice over and fry until golden on the other side. Add oil to the skillet if necessary and continue frying the plantain slices until all are done.

Drain thoroughly on paper toweling.

Serve for breakfast with fried or scrambled eggs, refried beans, and hot tortillas. The fried plantains are particularly delicious when topped with a dollop of Mexican crema (or sour cream).

Guamúchiles, available in central Mexico in April and May, just prior to the start of the rainy season.

This short series of photographs, recipes, and descriptions is just the beginning of your knowledge of the tropical fruits available season by season here in Mexico. Each harvest time brings new and different produce to our markets. We learn as we live here to anticipate certain local fruits at certain times of the year: fresas (strawberries) starting in February but available year-round; tiny orange-red wild ciruelas (plums) late in the summer; the tejocote (similar to a small crabapple) early in winter. There are other fruits gathered locally in the wild: the capulín (a kind of wild cherry) and the guamúchil (a small whitish, crisp fruit that grows on trees, in a twisted pod).

In central Mexico, strawberries are deliciously ripe all year long.

In addition, of course, we have oranges, grapefruit, pineapple, watermelon, cantaloupe, peaches, apricots, apples, pears, and tangerines in their seasons. All of these well-known fruits are generally picked in season and at the peak of ripeness here in Mexico and will cause you to lick your fingers, reach for seconds, and exclaim, "You know, I don't think I've ever really tasted one of these before!"

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.