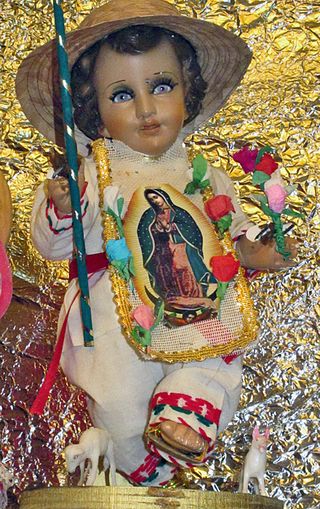

Niños Dios: one Christ Child, many colors: ideal for Mexico's range of skin tones. Mercado Medellín, Colonia Roma, Mexico City, December 2013.

For about a month prior to Christmas each year, the Niño Dios (baby Jesus) is for sale everywhere in Mexico. Mexico Cooks! took this photograph in 2013 at the annual tianguis navideño (Christmas market) in front of the Mercado Medellín, Colonia Roma, Mexico City. These Niños Dios range in size from just a few inches long to nearly the size of a two-year-old child. They're sold wrapped in only a diaper.

When does the Christmas season end in your family? When I was a child, my parents packed the Christmas decorations away on January 1, New Year's Day. Today, my wife and I like to enjoy the nacimientos (manger scenes), the Christmas lights, and the tree until the seventh or eighth of January, right after the Día de los Reyes Magos (the Feast of the Three Kings). Some think that date is scandalously late. Other people, particularly our many Mexican friends, think that date is scandalously early. Christmas in Mexico isn't over until February 2, el Día de la Candelaria (Candlemas Day), also known as the Feast of the Presentation.

The Holy Family, a shepherd and some of his goats, Our Lady of Guadalupe, an angel, a little French santon cat from Provence, and some indigenous people form a small portion of Mexico Cooks!' nacimiento. Click on the photo to get a better look. Note that the Virgin Mary is breast feeding the infant Jesus while St. Joseph looks on.

Although Mexico's 21st century Christmas celebration often includes Santa Claus and a Christmas tree, the main focus of a home-style Christmas continues to be the nacimiento and the Christian Christmas story. A family's nacimiento may well contain hundreds–even thousands–of figures, but all nacimientos have as their heart and soul the Holy Family (the Virgin Mary, St. Joseph, and the baby Jesus). This centerpiece of the nacimiento is known as el Misterio (the Mystery). The nacimiento is set up early–in 2013, ours was out at the very beginning of December–but the Niño Dios does not make his appearance until the night of December 24, when he is sung to and placed in the manger.

Niños Dios at Mexico City's Mercado de la Merced. The figures are dressed as hundreds of different saints and representations of holy people and ideas. The figures are for sale, but most people are only shopping for new clothes for their baby Jesus. All photos copyright Mexico Cooks! except as noted.

Between December 24, when he is tenderly rocked to sleep and laid in the manger, and February 2, the Niño Dios rests happily in the bosom of his family. As living members of his family, we are charged with his care. As February approaches, a certain excitement begins to bubble to the surface. The Niño Dios needs new clothing! How shall we dress him this year?

The oldest tradition is to dress the Niño Dios in hand-crocheted garments. Photo courtesy Manos Mexicanos.

According to Christian teaching, the Virgin Mary and St. Joseph took the baby Jesus to the synagogue 40 days after his birth to introduce him in the temple–hence February 2 is also known as the Feast of the Presentation. What happy, proud mother would wrap her newborn in just any old thing to take him to church for the first time? I suspect that this brand new holy child was dressed as much to the nines as his parents could afford.

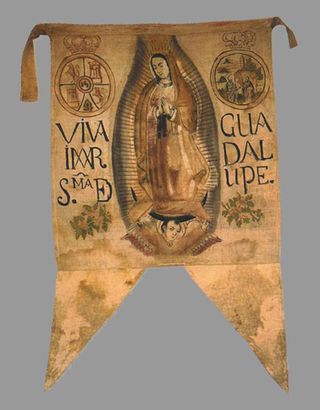

The Niño Dios dressed as San Juan Diego, the indigenous man who brought Our Lady of Guadalupe to the Roman Catholic Church.

Every February 2, churches are packed with men, women, and families carrying their Niños Dios to church in his new clothes, ready to be blessed, lulled to sleep with a sweet lullaby, and tucked gently away till next year.

The Niño Dios as el Santo Niño Doctor de los Enfermos (the holy child doctor of the sick). He has his stethoscope, his uniform, and his doctor's bag. This traditionally dressed baby Jesus has origins in mid-20th century in the city of Puebla.

Every year new and different clothing for the Niño Dios comes to market. In 2011, the latest fashions were those of the Archangels–in this case, the Archangel Gabriel.

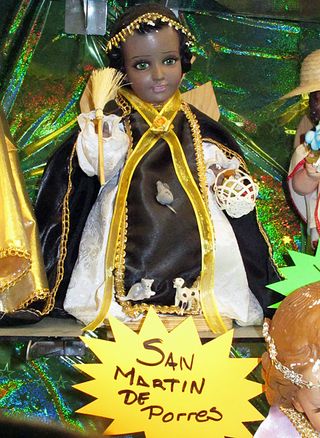

The Niño Dios dressed as Peruvian San Martín de Porres, the patron saint of racially mixed people and all those seeking interracial harmony.

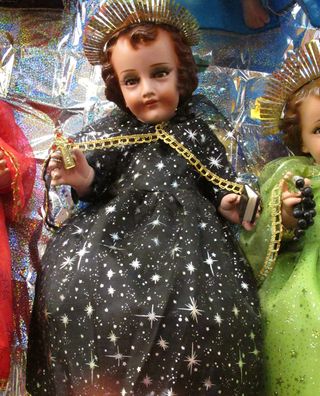

Niño Dios de la Eucaristía (Holy Child of the Eucharist).

Niño Dios dressed as San Benito, the founder of the Benedictine Order.

Niño Dios dressed as a Chinelo (costumed dancer from the state of Morelos).

Niño Dios de la Abundancia (Holy Child of Abundance).

The ceremony of removing the baby Jesus from the nacimiento is called the levantamiento (lifting up). In a family ceremony, the baby is raised from his manger, gently dusted off, and dressed in his new finery. Some families sing:

QUIERES QUE TE QUITE MI BIEN DE LAS PAJAS, (Do you want me to brush off all the straw, my beloved)

QUIERES QUE TE ADOREN TODOS LOS PASTORES, (Do you want all the shepherds to adore you?)

QUIERES QUE TE COJA EN MIS BRAZOS Y CANTE (Do you want me to hold you in my arms and sing)

GLORIA A DIOS EN LAS ALTURAS. (Glory to God on high).

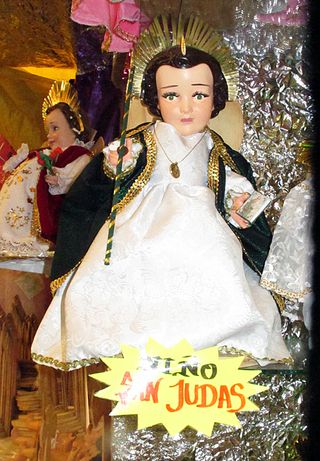

One of the most popular 'looks' for the Niño Dios in Mexico City is that of San Judas Tadeo, the patron saint of impossible causes. He is always dressed in green, white, and gold and has a flame coming from his head.

Mexico Cooks!' very own Niño Dios. He measures just 7" from the top of his head to his wee toes. His new finery is very elegant.

[youtube=://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h4rcQDmyffo&w=420&h=236]

This lovely video from Carapan, Michoacán shows both the gravity and the joy (and the confetti!) with which a Niño Dios is carried to the parish church.

Carefully, carefully carry the Niño Dios to the parish church, where the priest will bless him and his new clothing, along with you and your family. After Mass, take the baby Jesus home and put him safely to rest till next year's Christmas season. Sweet dreams of his next outfit will fill your own head as you sleep that night.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.