The center pathway at the Panteón de Belén (Bethlehem Cemetery) leads to this rotunda, the original Rotunda of Illustrious Men of Guadalajara. Patterned after an Egyptian pyramid, it contains crypts and a chapel.

When I was a child, a Sunday drive with my family often included a visit to one of the finest old cemeteries of the southern United States. My younger sister and I would wander among the elaborate limestone mausoleums, exclaiming at the dates that seemed so long ago, "Look, Mommy, this man died in 1822. Do you remember back that far?" My mother, born 100 years after that date, simply rolled her eyes and suggested that we hurry over to the cemetery pond to feed the ducks and swans from our bags of stale bread.

I still like to visit cemeteries. There's peace to be found among the dead, an acceptance of life as it is and death as it comes. The Day of the Dead in Mexico celebrates that notion: life is to be lived today, death is inevitable. Enjoy the one, honor the other. In Guadalajara, there is a cemetery where the long-dead are honored year round. You'll find plenty of entertainment in its legends and lore.

A few weeks ago, my friend Lourdes called just as I was leaving for the Panteón de Belén (Bethlehem Cemetery), Guadalajara's most famous burial ground. I thought she'd be squeamish when I asked her to meet me there, but no. She's a Guadalajara native, but she'd never been to the cemetery and she was quite excited at the prospect. She was beaming when we met at the ancient stone entrance. I paid our entry fee ($5 pesos per person, plus an extra $10 pesos if you plan to take pictures) and we started out along the center pathway through moldering gravestones and decrepit 19th Century mausoleums.

The construction of Panteón de Belén began in 1843 under the direction of architect Manuel Gómez Ibarra, who also built the towers of the Metropolitan Cathedral in Guadalajara. The cemetery had been in the planning stages since 1786, shortly after Guadalajara had passed through what has come to be called 'the year of hunger'. A tremendous plague gripped the city, killing thousands of its residents and filling the existing cemeteries. There was a tremendous need for a new campo santo (burial ground).

The colonnade of crypts at the front entrance of the Panteón de Belén.

City authorities chose the orchards of the civil hospital to build the new cemetery. Flat and extensive, the grounds were well-suited to this use. The first occupant of the cemetery, buried there in 1844 before the buildings were completed, was Isidoro Gómez Tortolero, pastor of the town of Tala, Jalisco.

Today, much of the cemetery has been closed and the remaining land used for other purposes. What we see now is only a fraction of what once existed. The lands that were used as the common graves of the poor are now under a huge building.

The portion of the cemetery where we walked (and where we found our admirable guide) is crumbling with age. Huge branching trees arch over the graves, the mausoleums, and the pathways. Mottled shade alternates with brilliant sunshine, creating the sense that we walked between the past and the present. Dates on the crypts carried us back in time, forcing our thoughts down paths that long-dead feet trod before us.

Legend and history had us in their grip. One minute Lourdes said, "I'm not the sort that is afraid in a place like this," and the next minute she showed me her arm, with gooseflesh and peach fuzz standing up in a chilly shiver. We stood silent, wondering which graves were the stuff of ghostly tales and which held the barely-remembered.

The inscription on Little Nacho's tomb reads, "Ignacio Torres Altamirano, May 26, 1882".

Suddenly we heard a high-pitched young voice saying, "And over here is Little Nacho, the one who was afraid of the dark." Our ears perked up. We looked for the source of the voice and saw a young girl, no more than nine or ten years old, leading a group of enthralled visitors around the cemetery. We begged permission to join them.

"See the child's stone coffin, built on top of the grave?" Her girlish voice turned very serious. "That's Little Nacho, who died exactly on his first birthday. From the time he was born, he was terrified of the dark and couldn't bear to be in a closed room. He had to sleep in a room filled with candles, a room where all the windows were open. The doctors were amazed by his fear, and nothing his parents could do would cure it. They even took him to curanderos(faith healers) to see if he was bewitched, but to no avail.

"When Little Nacho died, his parents buried him here in this grave, with a heavy gravestone above him. Everyone went home from the funeral and night fell. When the cemetery watchman made his rounds just at dawn, he jumped back in horror when he saw that Little Nacho's tiny coffin was lying on top of the gravestone. His report to the cemetery authorities was that someone had dug up the baby's coffin during the night, a desecration of the worst sort."

Very stylish in her pink skirt, Jessica Torres (at the far right), age ten, skillfully guided our group through the cemetery. Dramatic and articulate, she kept us all in shivers.

Our little group was riveted by what our young guide was saying. She continued, "That same day they buried his coffin again, but every morning for the next ten days it reappeared on top of the gravestone. No one had ever seen anything like it, and no one knew what to do. the cemetery authorities were trembling, but they finally had to tell the parents about these strange events.

"Little Nacho's grieving parents immediately knew the solution. 'Leave his coffin on top of his grave. He feared the dark in life. Of course he fears it in death as well.' And there it stayed, and here it still stays. Little Nacho rests above the ground."

Lourdes raised her hand. "And all those little toys and candies around the base of the tomb? Why are they there?"

Our guide smiled briefly. "They say that if you leave Little Nacho a piece of candy, your life in the future will be sweet."

We moved along to the next monument. Jessica Torres, our guide, stopped abruptly in front of a large carved stone tomb. "Two people are buried here, José María Castaños and Andrea Retes. They were so much in love and planning to be married, but the boy's mother hated the girl because she was from a lower social class.

"The two lovers were so upset by José María's mother's anger and hatred that they killed themselves. When his mother found out what happened, she almost went crazy from grief and guilt. She owned a plot in this cemetery and begged permission from Andrea's parents to bury the two lovers together. She had a double cross carved and placed on their tomb as a way of asking for God's forgiveness.

"Still, José María's mother's guilt would not leave her in peace. She knew she was the one responsible for the two deaths. Cry though she might, she could not get rid of the pain in her heart. Months later, she decided to take a wreath of flowers to lay on the grave. She draped the wreath over the double cross, just the way a lasso (ceremonial rope symbolizing marital union) is draped over the bride and groom at their wedding.

"A sudden silence fell over the cemetery as José María's mother laid the wreath over the cross. Even the birds stopped singing. In that silent instant, the wreath of beautiful fresh flowers turned to stone, just the way we see them today. And with that sign, José María's mother finally believed that the two young lovers had forgiven her."

In 1996 the stone crosses on the Castaños tomb fell and suffered some damage, but they remain united by their wreath of flowers.

Whispering among ourselves about the stories we'd heard, our not-so-brave little band followed behind Jessica as she led us toward the next grave site. One of the women with us murmured, "I hear they have night tours here. I don't think I'd have the courage to come here in the dark. It's scary enough in the broad daylight."

Jessica turned around. "There are night tours, on Fridays and on some special days, too. There will be night tours celebrating the Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) this year. In fact, it's a marathon. Four tours will start every hour or so, beginning at seven o'clock at night and lasting all night long. The whole cemetery will be full of people."

Lourdes and I looked at one another and nodded. "I wouldn't miss it, would you?" she whispered.

Our next graveside stop was at the tomb of the sailor. Jessica told us that unlike other legendary Navy men, this sailor did not have a girl in every port. Instead, he had an enemy in every port. Sailing Mexico's west coast, he stole jewelry, gold coins, and everything else of value he could expropriate from the rightful owners. The sailor was a pirate, and he had a huge stash of valuables.

The tombstone of el marinero (the sailor), who buried a huge bag of gold coins—somewhere. Will you be the one to learn the secret?

"Only he knew where the booty was. Even though he had a son, he never told even his son where all the treasure was hidden. When the sailor was very old, he moved to Guadalajara and spent his last few months of life here. When he died, the secret of his treasure died with him."

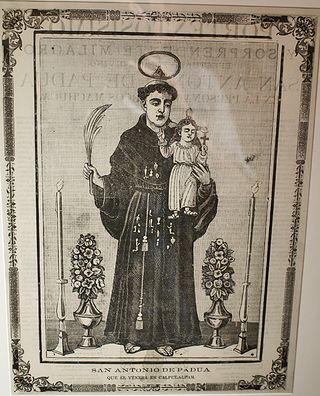

Jessica smoothed her pretty pink skirt. "They say that you have to light a candle and pray the rosary with all your heart, right here at his grave at midnight. But you have to do it without fear, and many people have tried. They're not afraid when they start out, but about half way through the rosary something happens. They start trembling with fear, and they have to give up and run away. No one has ever made it through a whole rosary, but if you want to try it some midnight, they say that the ghost of the sailor will come out from behind the grave stone and tell you where the treasure is hidden." She shook her finger. "You won't find me here at midnight!"

I was surprised to see two side-by-side crypts with epitaphs in English. When I looked closer, I could see that the husband and wife were natives of Paisley, Scotland. Lourdes asked me, "How can you tell that they were married?"

I pointed out the word wife engraved into the marble of Jean Young's crypt marker. "That means esposa," I whispered to Lourdes.

Joseph Johnston, a doctor from Scotland, and his wife, Jean Young, are buried side by side in two crypts. They both died in Guadalajara in 1896.

Jessica was telling the story. "The man buried here was a doctor, but not one of those doctors who was only in the profession for the money. In fact, most of the time he didn't even want to accept payment for curing people. He did it from his heart. Nobody knows how he arrived in Guadalajara, but he and his wife both died here in 1896. And today, if you come to their graves and ask for a favor while you're praying the rosary, the couple will take charge of seeing to it that you have a lot of good luck, good health, and all the money you need." She looked at us and smiled. "And love, too. They'll make sure that the one you love also loves you. But you have to be praying from the heart."

Just one of the hundreds of crypts in Guadalajara's Panteón de Belén.

Those buried in the Panteón de Belén range from the highest of Guadalajara's 19th Century high society to the poorest of the poor, who were buried in common graves in the furthest part of the cemetery grounds. Among the elite are Ramón Corona, a governor of Jalisco; Enrique Díaz de León, the first rector of the University of Guadalajara; José Silverio Núñez, the second governor of Colima; and Carlos Villaseñor, a painter whose ashes now rest in the Rotonda de Hombres Ilustres across the street from the Metropolitan Cathedal. A glance at the list of important people buried in the cemetery is like reading a list of the street names of Guadalajara.

There are also graves marked only with a first name: Rafael, Enrique, Joaquín. These are children born out of wedlock. Rather than shame the mother, the child was buried with no last name on the tombstone.

There are many, many more legends to tell from the Panteón de Belén. We heard about the woman who was buried alive, the hanging tree, the night watchman, the horse and carriage, the empty tomb that bears a name, the priest shot by a firing squad, the student gone crazy—there are all of these tales and more to make the blood run just a little cold.

A Mexican girl's quinceañera (15th birthday celebration) is the most important day of her life, the day she leaves her childhood behind and is presented to God and to society as a young woman.

Today, the cemetery is a popular spot for portraits. Quinceañeras (young women celebrating their fifteenth birthdays) dressed in fabulous gowns and carrying beautiful bouquets are photographed every day of the week. Lourdes and I saw two lovely young women, one in floor length, pale pink tulle and the other in cream satin with puffed sleeves, each being photographed next to carved pilasters. Newlyweds arrive after their weddings on Saturday afternoons, the brides radiant as they lean against a 19th Century mausoleum and smile into their new husbands' eyes.

The cemetery is romantic, it's beautiful, and it's an island of peace in the heart of Guadalajara. Here among the ghosts and legends of the past, today's young people celebrate their new lives.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.

Disclaimer: Marca País-Imágen de México is a joint public and private sector initiative designed to help promote Mexico as a global business partner and an unrivaled tourist destination. This program is designed to shine a light on the Mexico that its people experience every day. Disclosure: I am being compensated for my work in creating content for the Mexico Today program. All stories, opinions, and passions for all things Mexico that I write on Mexico Cooks! are completely my own.

For their weddings, Zinacantán women wear the k'uk'umal chilil, an elaborately woven huipil (long blouse). White feathers are woven among the colored borders of these wedding dresses, which are nearly long enough to reach the ground. Under the huipil, the bride wears a finely hand woven and embroidered navy blue woolen skirt. The bride's white dress takes approximately five months to weave on a back strap loom. The people of Zinacantán say that the hen is a domestic animal that has feathers but cannot fly, walks on two legs just like people, is dependent on them for its nourishment, and is always near the house even when it runs loose. So the feathers that women weave into the bridal garment represent the attitude of the hen, which the bride is expected to adopt: she will not leave the household, even though she is capable of doing so, and she will shape a relationship of interdependence with her husband. Hence the feathers are a symbol of good marriage, as are the three borders of multicolored embroidery. In addition to the long blouse and the navy blue skirt, the bride wears a long white embroidered shawl which covers most of her head and face during the marriage ceremony.

For their weddings, Zinacantán women wear the k'uk'umal chilil, an elaborately woven huipil (long blouse). White feathers are woven among the colored borders of these wedding dresses, which are nearly long enough to reach the ground. Under the huipil, the bride wears a finely hand woven and embroidered navy blue woolen skirt. The bride's white dress takes approximately five months to weave on a back strap loom. The people of Zinacantán say that the hen is a domestic animal that has feathers but cannot fly, walks on two legs just like people, is dependent on them for its nourishment, and is always near the house even when it runs loose. So the feathers that women weave into the bridal garment represent the attitude of the hen, which the bride is expected to adopt: she will not leave the household, even though she is capable of doing so, and she will shape a relationship of interdependence with her husband. Hence the feathers are a symbol of good marriage, as are the three borders of multicolored embroidery. In addition to the long blouse and the navy blue skirt, the bride wears a long white embroidered shawl which covers most of her head and face during the marriage ceremony.