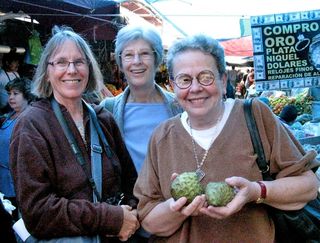

A November market tour on a chilly morning in Pátzcuaro, Michoacán: from left, Charlotte Ekland, Donna Barnett, and Mexico Cooks!. Marvey Chapman, the other member of this tour group, took the picture. I'm holding two Michoacán-grown chirimoyas (Annona cherimola), known in English as custard apples.

One of the great pleasures of 2012 was the number of tours Mexico Cooks! gave to lots of excited tourists. Small, specialized tours are a joy to organize: the participants generally have common interests, a thirst for knowledge, and a hunger for–well, for Mexico Cooks!' tour specialty: food and its preparation. Touring a food destination (a street market in Michoacán, an enclosed market in Guadalajara, a crawl through some Mexico City street stands, or a series of upscale restaurants) is about far more than a brief look at a fruit, a vegetable, or a basket of freshly made tortillas.

A Pátzcuaro street vendor holds out a partially unwrapped tamal de trigo (wheat tamal). It's sweetened with piloncillo (Mexican raw sugar) and a few plump raisins, wrapped in corn husks, and steamed. Taste? It's all but identical to a bran muffin, and every tour participant enjoyed a pinch of it.

A tour planned to your specifications can lead you to places you didn't know you wanted to go, but that you would not have missed for the world. Here, Donna talks with the man who makes these enormous adobe bricks. He let her try to pick up the laden wheelbarrow. She could barely get its legs off the ground! He laughed, raised the handles, and whizzed away with his load.

Twice in 2012 small groups wanted to tour traditional bakeries in Mexico City. The photo shows one tiny corner of the enormous Pastelería La Ideal in the Centro Histórico. Just looking at the photo brings the sweet fragrances back to mind.

Ramon and Annabelle Canova wanted an introduction to how ordinary people live and shop in Guadalajara. We spent a highly entertaining morning at the Tianguis del Sol, a three-times-a-week outdoor market in Zapopan, a suburb of Guadalajara. Our first stop was for breakfast, then we shopped for unusual produce, fresh spices, and other goodies that the Canovas don't often see in their home town. Annabelle said she felt right at home because so much of the style and flavor of this market was similar to what she experienced in the markets near her home town in the Phillipines.

We went to the original location of Guadalajara's Karne Garibaldi for comida (main meal of the day). The restaurant does one thing–carne en su jugo (meat in its juice)–and does it exceptionally well. The food is plentiful, delicious, and affordable. The place is always packed, and usually has a line to get in!

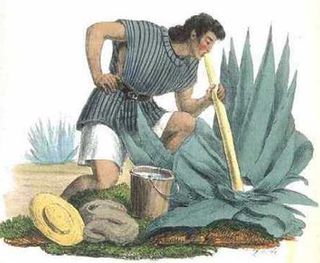

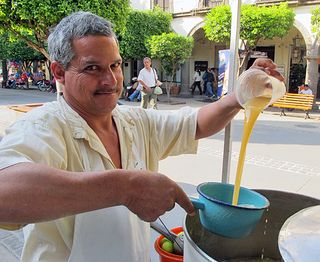

Ramon wanted to try tejuino, a regional specialty in the Guadalajara area. Mixed when you order it, the refreshing, lightly fermented drink is thickened with masa de maíz (corn dough) and served with a pinch of salt and a small scoop of lemon ice.

Pillars of nopal cactus paddles, taller than a man, at Mercado de la Merced, Mexico City. La Merced is the largest retail market in Mexico, if not in all of Latin America. It's the ultimate market experience and just a partial tour takes the best part of a morning. Comfortable walking shoes are a necessity–let's go!

A more intimate, up-close-and-personal Mexico City market tour takes us through the Mercado San Juan. The San Juan is renowned for its gourmet selection of meats, fish and shellfish, cheeses, and wild mushrooms–among a million other things you might not expect to find.

Pepitorias are a sweet specialty of Mexico's capital city. Crunchy and colorful obleas (wafers) enclose sticky syrup and squash seeds. Mexico Cooks!' tour groups usually try these at the Bazar Sábado in San Ángel.

Lovely and fascinating people and events are around almost any Mexican corner. The annual Festival Internacional de Música de Morelia opens every year with several blocks of carpets made of flowers. Residents of Patamban, Michoacán work all night to create the carpets for the festival. This piano is made entirely of plant material. Enlarge any picture for a closer view.

Entire flowers, fuzzy pods, and flower petals are used to create the carpets' ephemeral beauty and design; these carpets last two days at most.

In November 2012, one of Mexico Cooks!' tours was dazzled by a special Morelia concert given by Tania Libertad. With Tania is Rosalba Morales Bartolo from San Jerónimo, Michoacán, who presented the artist with various handcrafted items from the state.

No matter where we start our tour and no matter what we plan together for your itinerary, a Mexico Cooks! tour always includes a terrific surprise or two, special memories to take home, and the thirst for more of Mexico. Marvey Chapman had a wonderful time! By all means come and enjoy a tour!

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.