A waiter at Morelia's Tortas Ahogadas Guadalajara restaurant, on the run with a tray full of delicious tortas and tacos ahogados for hungry customers.

Mexico Cooks! lives in a beautiful and primarily residential neighborhood of Morelia, Michoacán. However, just down our street and around a couple of corners is a wide street lined on both sides with small businesses. On Wednesdays, our weekly tianguis (street market) sets up in a plaza on the west side of that street. A wonderful La Michoacana ice cream store is next to the market, along with an upholsterer, a small discount pharmacy, a stained glass maker, an upscale kitchen design center, a shoe store or two, and several take-out food shops.

The torta ahogada from Tortas Ahogadas "El Chile".

Best of all, this street is home to at least three–or four, or maybe more–open-air restaurants that specialize in tortas ahogadas, the signature 'drowned' sandwich from Guadalajara. The torta ahogada is a like a French dip sandwich gone crazy. The restaurant-lined boulevard is affectionately known as el boulevard de la torta (Sandwich Row). Every restaurant is popular and every diner has his or her favorite torta: this bread is more 'authentic', that sauce has more chispa (spark), the outside edges of this pork filling are crisper. It's the kind of debate that creates conversation and friendly argument for years, not unlike the debate over thin versus thick crust pizza, Coke versus Pepsi, and soft-serve versus scooped ice cream.

Tortas Ahogadas "El Chile" opened about six months ago. The afternoon we were there, our table and two others had a total of six customers, although the restaurant seats about 50. It's hard to be the new kid on the block.

Mexico Cooks! decided to take on the down-and-dirty job of taste-testing three of these tortas ahogadas joints. As Judy pointed out, "It's in the name of research, you know. It's a tough job, but somebody's got to do it." To keep the taste-test fair, Judy got to order whatever she wanted, but I ordered the same style torta at each of the three restaurants. We dined at each place at about three o'clock in the afternoon, prime time for the main meal of the day in Mexico.

Long lines, day after day after day, are the hallmark of Tortas Ahogadas Guadalajara. This Morelia restaurant has been serving tortas ahogadas and little else for 17 years. The restaurant seats about 150 people and has an equally busy second location just a few blocks away.

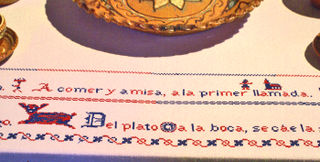

The formula for a torta ahogada is simple: split open a crusty, densely crumbed birrote salado (sugarless white flour sandwich roll), fill it with lean chopped pork, thoroughly drench the sandwich with a tomato-y salsa picante (hot sauce), and top with thinly sliced pickled onions. It's that easy, and it's that complex. For starters, where does the restaurant get its bread? It's almost impossible to find a real birrote salado outside Guadalajara. Is the pork overcooked and mushy, is it tender with those crispy, caramelized edges, is it fatty? Does the salsa have just the right amount of vinegar, just the right amount of chile de árbol, just the right amount of tomato? Are the pickled onions white onions or red onions? Restaurant rivalries are born from these differences, as are friendly debates over the merits of various tortas.

The torta ahogada at Tortas Ahogadas Guadalajara.

Originally from Guadalajara and still served at carts, stands, and restaurants everywhere in that city, the quintessential torta ahogada is best eaten at Estadio Jalisco during a game of fútbol (soccer) while the sauce runs down your hands and arms. Tapatíos (nickname for a Guadalajara resident) or not, people now snarf down tortas ahogadas all over Mexico.

The sign at Ahogadas Jalisco reads, "Here and now and for many years, we are Ahogadas Jalisco, giving you, your family and your friends something different." Ahogadas Jalisco seats about 80 people and has been in business for seven years. It was jammed with customers the day Mexico Cooks! ate there.

Anywhere you eat a torta ahogada, you ask for it brought to you at just the level of picante you like: 1/4, 1/2, 3/4, or muerta. One-quarter means that the sauce for 'drowning' your sandwich is mostly very thin tomato sauce mixed with a quick hit of chile. One-half means the sauce will be twice as hot as the 1/4. Three-quarters…well, you get it. Muerta means that your sauce will be 100% chile, no tomato. Muerta

means DEAD, and you might well be if you eat this and aren't accustomed

to its substantially more than intense level of mouth heat. For

research purposes, I ordered mine media (half) and added more chile as required.

The torta ahogada at Ahogadas Jalisco.

Here's a recipe:

Torta Ahogada Estilo Guadalajara (Guadalajara Style 'Drowned' Sandwich)

600 grams fresh ripe tomatoes

50 grams chile de árbol

pinch of pepper

pinch of salt

1 clove of garlic

1 bay leaf

Water

2 whole cloves

2 Tbsp white vinegar

1 tsp oregano, preferably Mexican

1 medium white onion, minced

600 grams thinly sliced freshly made carnitas

12 birrote salado or other small loaves of crusty, dense bread

Thinly sliced pickled onions for garnish.

Cook the tomatoes, minced onion, and garlic in water, until soft. Drain, reserving cooking liquid. In a blender, blend until as smooth as possible. Use cooking liquid to thin as necessary; the salsa should be quite thin. Strain. Season to taste with salt and pepper. Reserve.

Cook the chiles. Add vinegar, oregano, cloves, and salt to taste. In a blender, blend until very smooth. Strain. Reserve.

Split open the birrotes, leaving the top and bottom halves hinged together. Put each one on its serving plate (a shallow soup plate is the best). Pack 100 grams of sliced carnitas into each birrote.

Ask each of your comensales (diners) how much picante he or she wants on the torta and custom-mix the chile you prepared with the reserved tomato sauce. Douse the torta very liberally inside and out with the sauces your guests requested. The sandwich should be soaked and swimming in sauce. Garnish with pickled onions, and serve.

Serve bowls of chile and bowls of thin tomato sauce on the side so your guests can add more of either.

Serves six.

These young Morelia beauties ordered tacos ahogados and shared a papa rellena (stuffed potato) at Ahogados Jalisco. For an order of three tacos, the restaurant covers crisp-fried tacos de carnitas with tomato and chile sauce to your taste, then tops it all with shredded cabbage and pickled onions.

All three restaurants are bargains. A torta ahogada costs about 15 pesos, an order of three tacos ahogados costs about 18 pesos. All of the restaurants offer soft drinks, beer, and aguas frescas at reasonable prices. Some of the restaurants have specialties other than standard tortas. For example, El Chile has tortas y tacos ahogados de camarón (shrimp) on the menu and Ahogadas Jalisco sells addictive papas rellenas (baked potatoes stuffed with thin-sliced fried ham, melted cheese, and mustardy cream sauce and garnished with a chile toreado).

The outstanding papa rellena (stuffed potato) at Ahogadas Jalisco.

Just for you, Mexico Cooks! sacrificed herself on the altar of culinary research and ate tortas ahogadas for days, to the point that Judy laughingly said the next stop was Peptobismolandia. Which tortas were the best?

We loved the tortas at Tortas Ahogadas Guadalajara for several reasons: the delicious, crisp-along-the-edges meat, the marvelous flavors of the sauce, the ambiance (including the recorded music), at the jumping restaurant, the attentive service. The bread at Ahogadas Jalisco was the best, the tacos ahogados were great, and we swooned over the papa rellena. The owner at Tortas Ahogadas El Chile was completely accommodating and trying his best to succeed, but his restaurant has a hard act to follow: it's right across the street from Tortas Ahogadas Guadalajara, the major player on el boulevard de la torta. You'll have to visit Morelia and try them all yourselves!

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.