This traditional Mexican kitchen dates to the early part of the 20th Century.

Home cooking for you might be your mother's macaroni and cheese. For my

friend Shana it's her grandmother's potato latkes, for Danny it's the

fond memory of his Aunt Ethel's apple crumble. And for me? For the last 30 years, my taste buds and heart have been drawn by the smells and

flavors of the Michoacán home kitchen.

The first kitchen fragrance that fills my memory is that of pine wood

burning in the clay stove centered in the mountain kitchen. One note

behind the wood smoke is the scent of beans boiling in a clay pot, and

the fragrance chord is finished by a top note of tortillas toasting on

the clay comal (a

large flat clay griddle). The home kitchen closest to my heart belongs

to Débora, my friend who lives at more than 9500 feet above sea

level, about two-thirds of the way up the highest mountain in Michoacán.

Thick, handmade Michoacán blue corn tortillas baking on a clay comal.

When I visited Débora at home for the first time, my entire notion of

how a house looks was turned upside down. My friend Celia (Débora's

sister) had invited me to travel home with her for two weeks:"Ven conmigo a mi tierra, a conocer a mi mamá,"

she said. ("Come with me to my hometown, to meet my mother.") Thirty years ago, we

traveled for 52 hours, from Tijuana to what I often tease Débora as being el último rinconcito del mundo

(the last little corner of the world), by train and by three different classes of bus. The last 27 kilometers of the

trip (approximately fifteen miles) was a jolting three hour ride in a converted school bus, on an unpaved road. You read that

right: three hours to drive fifteen miles. We were traveling on a dirt road that wound nearly

straight up the mountainside.

From the bus stop in front of the mayor's office we walked two blocks up another hill and opened a

small door in a long wall. We walked up three wide slate steps into a dirt

patio—and the house? I looked around, wondering where the house was.

Outdoor kitchens like this one are still common in Michoacán's rural areas.

I could see one room with a door (the bedroom, I found out later,

complete with three rope beds and their corn husk mattresses), and

a sitting-eating-sewing-talking room that had only three walls and

was open to the air. The kitchen was a tiny room with an opening

but no door to close. That was the entire home.

Looking around, I saw chickens picking and scratching all over the dirt floor of the central patio, the pila

(a single-tap cold water concrete sink used for washing clothes and dishes), an

outdoor beehive clay oven, a path that I later discovered led to the

outhouse, and a tiny, elderly woman wrapped in a rebozo

(typical shawl) sweeping with a broom made of twigs: Celia's mother.

Flowering trees and shrubs surrounded the patio; enormous dahlias in

all colors blessed the wildness of the garden.

Tired from the long trip, I was soon put to bed at Aunt Delfina's house next door.

Early, early the next morning, I stuck my head out the spare

bedroom door and saw mist hanging among the mountains. I sniffed

the clean scent of pine smoke in the chilly air. A hint of coffee fragrance

followed, and the toasty corn smell of freshly handmade tortillas

cooking. I dressed and went to see what Débora was doing next door in

that tiny kitchen.

The metate y mano (three-legged volcanic stone grinding stand and its rolling pin) have been in use since centuries before the Spaniards arrived in the New World.

Débora was outside, standing near an outdoor stove made of a vertical oil drum. She was grinding

nixtamal (dried

corn prepared for making dough) on a metate (grinding stand) and patting out tortilla

after tortilla, placing them onto the clay comal on top of the stove to cook. We smiled buenos días

to one another and she gestured to offer me a fresh hot tortilla. I ate

it eagerly and excused myself and went to peek into the kitchen.

What I saw astonished me. In the center of the dim windowless kitchen

was a rectangular stove made of clay, plastered over and colored deep

brick red.

The four burners were six-inch diameter holes on top of the stove.

Below each burner hole was a long horizontal compartment for inserting

and burning split pine wood. The center chimney took most of the smoke

out through the roof.

Wooden shelves holding dishes and clay cooking pots hung on the neatly

whitewashed walls. On a low

ledge, several kinds of fresh and dried

chiles were piled on reed mats. A few cobs of dried corn, a plate of

fresh pan dulce,and

some fruits I didn't recognize were arranged on a small wooden table.

Above my head, aged woven reed baskets filled with foodstuffs—dried

corn, flour, coffee, a bag of beans—hung from smoke-blackened beams.

A votive candle burned in the corner near a small print of Our Lady of

Guadalupe. A jelly glass filled with garden dahlias graced the tiny

altar. A steaming clay pot of beans for the midday meal burbled on a

stove burner.

Typical bean pots made in Capula, Michoacán. If you need one, just tell the vendor the weight of the beans you usually cook: half a kilo, a kilo, or more at a time. The vendor will show you a pot of the correct size.

I gazed at this amazing kitchen with awe. There were no modern

conveniences at all, not even a sink or refrigerator. As I stared, Celia

stepped in and smiled at me. "This is the way the kitchen has been

since long before I was born," she said. "My great-grandmother cooked

here, my grandmother cooked here, my mother cooked here, and Débora and

I learned to cook here. All that we know of the kitchen is from here."

She gestured to encompass the tiny space.

"How does Débora keep food like milk and leftovers cold?" I asked.

Celia thought for a minute. "The milkman comes on his horse

every morning and sells her just what she thinks she'll need for the

day. He dips the milk out of his big metal milk can with a liter

measure and pours it into one of her clay pots. If there's a bit left

over at the end of the day, she gives it to the cat or she mixes it with really stale

tortillas for the pig.

The local butcher sells Débora exactly the quantity of meat she needs to prepare each day's comida (main meal of the day). In Mexico's small towns, a red flannel flag hanging on a pole outside the shop is the indication that the butcher has freshly-butchered meat.

"Débora only buys enough meat for today, and it's always meat that is recién matada

(butchered today). The meat that's killed and wrapped in plastic to be

sold in the big markets—who knows how old that is! It never tastes as

good as today's freshly cut meat.

"Then if there is food left over from la comida (the

midday meal), we eat it for supper later. If there's still a little

left, she gives it to the pig. Nothing goes to waste. And if she buys a

few limones (Mexican limes), she buries them in the ground to keep them fresh."

"What else will you teach me while I'm here?" I asked.

Celia shook her head. "This time you just watch and pay attention. Next time you can try your hand in the kitchen."

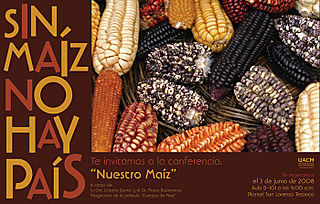

Many of the traditional recipes from Michoacán have their roots in the Purhépecha culture. Corundas, uchepos, minguiche, churipo—the first two are types of tamales, the third is a cheese dish and the fourth a soup—are just-post-Conquest Purhépecha recipes and are only a few of the many dishes that make Michoacán's cuisine extraordinary.

There are other Mexican recipes that, while not unique to Michoacán,

have strong ties to the state. There are some recipes which you may

want to try to duplicate in your home kitchen. If you're not able to

purchase all of the ingredients you need for these recipes, buy a

ticket instead and come to taste the cuisine of Michoacán in its

natural habitat. I'd be glad to take you on a food-tasting adventure.

Queso Cotija (cheese from Cotija, Michoacán) is aged–like fine wine–before being sent to market.

Many recipes from Michoacán include both corn and cheese,

cornerstones of the daily diet. Corn is one of Mexico's native grains

and Mexico, especially the state of Michoacán, is famous for its

cheeses. Cotija

(coh-TEE-hah), a town in Michoacán, has given its name

to the aged cheese used for topping refried beans and other dishes. If

you can't find it in your grocer's cheese case, you can substitute

another aged, crumbly cheese.

Chiles are also an important part of the Michoacán diet. Nearly all of the

fresh and dried chiles available everywhere in Mexico are found in the

state, as well as at least one variety that grows almost exclusively in Michoacán,

the chile perón. Chile perón

is approximately the size of a golf ball and is bright yellow to orange

in color. It has black seeds, a fruity flavor, and is extremely hot. On

a scale of one to ten, it registers about an eleven!

The beautiful and muy picante (very spicy!) chile perón is used extensively in the cuisine of Michoacán. It's also known as chile manzano–and is the only chile in the world with black seeds.

The corunda is a traditional Michoacán tamal that can be made

either with or without a filling. These are made with a cheese and mild

chile filling and are served with cream and a spicy salsa.

Corundas Michoacanas (Michoacán Corn tamales)

For the corundas:

3 kilos masa (corn dough) (if there is a tortillería near you, buy it there)

2 cups water

1 kilo (2.2 pounds) pork lard or vegetable shortening

5 Tablespoons baking powder

Salt to taste

30 fresh green corn stalk leaves (NOT the dried corn husks sold for ordinary tamales)

For the filling:

1 kilo queso doble crema (similar to cream cheese, which you can substitute)

1/2 kilo chiles poblanos, roasted, peeled, seeded, and cut into strips 2" long by 1/4" widePreparation:

With a large wooden spoon, beat the corn dough and the water together for approximately 30 minutes. Set aside.With another large wooden spoon, beat the lard until it is spongy. Add

the beaten dough to the lard, together with the baking powder and the

salt. Continue beating until, when you put a very small amount of the masa in a cup of water, it floats.Take a fresh corn stalk leaf and place three tablespoons of dough on

the thickest side of it. Make a small hollow in the dough and put a

tablespoon-size piece of the cheese and three or four strips of chile in the

hollow. Cover the cheese and chile strips with another three tablespoons of

the dough. Fold the corn stalk leaf over and over the dough until it

has the triangular shape of a pyramid.Continue making corundas until all the dough is used.

Put three cups of water in the bottom of a large steamer pot or tamalera. Use the rack that comes with the steamer pot to hold the first layer of corundas. Place all the corundas

in the pot, cover, and bring to a boil. Lower the heat so that the

water is actively simmering but not boiling. Be careful during the

steaming process that the water does not entirely boil away; check this

from time to time. Put a coin or two in the bottom of the tamalera; as the water boils, the coins will rattle. When you no longer hear the rattle, add more water immediately.Allow the corundas to steam for one hour and then

uncover to test for doneness by unwrapping one to see if the dough

still sticks to the corn stalk leaf. If it still sticks, steam for

another half hour. When the leaf comes away from the dough without

sticking, the corundas are done.Salsa:

1/2 kilo (1 pound) tomates verdes (called tomatillos in the United States), husks removed

6-8 chiles perón (substitute chiles serrano if necessary), washed

1 small bunch fresh cilantro, washed

Sea salt to tasteWash the tomatillos until they are no longer sticky. Fill a large saucepan half full with water and bring to a boil. Add the tomatillos and the chiles and boil until the tomatillos begin to burst open. With a slotted spoon, remove each tomatillo from the pot. When all of the tomatillos are in the blender, add the chiles

to the blender. Cover and blend at a low speed until the ingredients

begin to chop well, and then stop the blender. If your blender has a

removable center piece in the cover, add the cilantro little by little

through that hole as you turn the blender back on to 'liquefy'. If the

cover has no center hole, add some cilantro, blend, stop, and add more

cilantro until all is blended. Do not chop the cilantro too finely, as

you want flecks of it to help give the salsa both color and texture.

Add salt to taste and stir.To serve the corundas:

Unwrap a corunda and place it in a shallow soup bowl. Spoon unsweetened heavy cream over the corunda and top with several spoonfuls of the salsa.

Making any sort of tamales (including corundas)

is hard work and is always more fun if you can plan to do it with a

friend or two. Let the kids help, too. Make a party of it, with the big

reward—the eating—at the end.

A corunda with salsa and crema, served by Doña Ofelia at her stand near the Basílica de Nuestra Señora de la Salud (Our Lady of Health) in Pátzcuaro.

There will be plenty of corundas left over for everyone to take some

home for the next day. It's easy to reheat them. Just leave them

wrapped in their corn stalk leaves when you put them in a plastic bag

to refrigerate them. Then when you're ready to reheat, place as many as

your microwave will hold in a Pyrex dish. Cover them with paper

toweling and microwave on high until they are hot throughout. They're

just as good left over and they also freeze well.

Looking for a

tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.