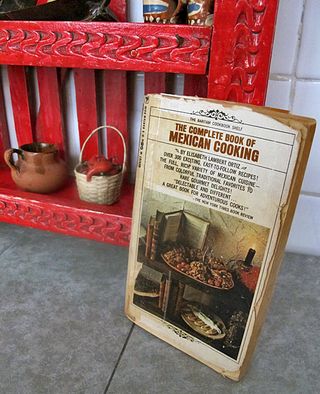

These and just a few other ingredients for albóndigas de Jalisco (Jalisco-style meatballs) combine to become a simple but delicious meal.

It's been cool during the day here in Mexico City for the couple of

months since the rainy season finally got itself underway. Summer in

Mexico's Central Highlands is my favorite time of year: cool-to-warm

partly sunny days are nearly always followed by downright chilly rainy

nights.

For those of you who live in the USA or Canada, it's hard to realize

that at more than 7500 feet above sea level, Mexico City has weather

completely unlike what many think of as Mexico's desert or even beach

temperatures. In the last few days, the afternoon high temperatures

have hovered just under 70° Fahrenheit. In Mexico Cooks!' household, cool days always mean something warming and delicious for our comida (midday meal). Subtly-flavored albóndigas–especially as prepared from this recipe, adapted from Diana Kennedy's book The Cuisines of Mexico–are the perfect comfort food.

You only need to blend eggs and a few herbs and spices to give a most wonderful Mexican touch to the meat mixture for these albóndigas (meatballs).

This is a dandy recipe for cooks of any level: if you're a beginner,

you'll love the simplicity and authenticity of the traditional flavors of the end

product. If you're a more advanced cook, the people at your table will

believe that you worked for hours to prepare this traditional Mexican

meal.

All the ingredients you need are undoubtedly easy for you to get even

if you live outside Mexico. Here's the list, both for the meatballs

and their sauce:

Ingredients

Albóndigas

1.5 Tbsp long-grain white rice

Boiling water to cover

3/4 lb ground pork

3/4 lb ground beef

2 small zucchini squash (about 6 ounces)

2 eggs

1/4 scant teaspoon dried oregano

4 good-sized sprigs fresh mint (preferably) OR 1 tsp dried mint

1 chile serrano, roughly chopped

3/4 tsp salt

1/4 scant teaspoon cumin seeds OR ground cumin

1/3 medium white onion, roughly chopped

Add the liquified eggs, onions, chile, herbs, and spices to the ground meats and mix well with your hands.

Sauce

3 medium Roma tomatoes (about 1 lb)

1 chile serrano, roughly chopped (optional if you do not care for a mildly spicy sauce)

Boiling water to cover

3 Tbsp lard, vegetable oil, peanut oil, or safflower oil (I prefer lard, for its flavor)

1 medium white onion, roughly chopped

5 cups rich meat or chicken broth, homemade if possible

Salt to taste

For serving

2 or 3 carrots, cut into cubes or sticks

2 medium white potatoes, cut into cubes or sticks

Utensils

A small bowl

A large bowl

A blender

A saucepan

A fork

A large flameproof pot with cover

Preparing the meatballs

Put

the rice in a small bowl and cover with boiling water. Allow to soak

for about 45 minutes. I use the glass custard cup that you see lying on

its side in the initial photo–it's just the right size.

While the rice is soaking, put both kinds of meat into the large

bowl. Trim the ends from the zucchini and discard. Chop the squash

very finely and add to the meat mixture.

Put the eggs, onion, and

all herbs and spices–in that order–in the blender jar. Blend until

all is liquified. Add to the meat/squash mixture and, using your hands,

mix well until the liquid is thoroughly incorporated.

Rinse out the blender jar for its next use in this recipe.

Drain the rice and add it to the meat mixture. Form 24 meatballs, about 1.5" in diameter, and set aside.

Preparing the sauce

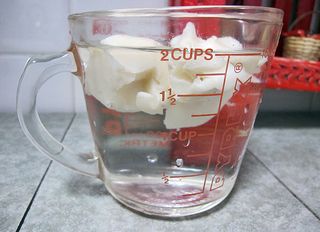

Bring

about 2 cups of water to a full rolling boil. Add the whole tomatoes

and allow to cook for about five minutes, until the skins split. Watch

the pot, though: this procedure might take a bit less or a bit more

time.

When

the tomato skins split, take the tomatoes one by one out of the water

and peel them. If you've never tried it, believe me: this is

miraculously easy–the skins are not too hot to handle and they slip off

the tomatoes like little gloves. You can see that I have stuck a fork

into the stem end of the tomato for ease of handling.

Skin the tomatoes and put them in the blender jar. Add the

roughly-chopped onion and chile serrano. Blend until thoroughly puréed.

Freshly rendered manteca

(lard) for frying the sauce. If all you can get in your store is a

hard brick of stark white, hydrogenated lard, don't bother. It has no

flavor and absolutely no redeeming value. If you want to use lard, ask a

butcher at a Latin market if he sells freshly rendered lard. If none

is available, use the oil of your choice.

In the flameproof cooking pot, heat the lard or oil and add the

tomato purée. Bring it to a boil and let it cook fast for about three

minutes. Splatter alert here!

Turn down the flame and add the broth to the tomato sauce. Bring it

to a simmer. Add the meatballs, cover the pot, and let them simmer in

the liquid for about an hour.

After

the first hour of cooking, add the carrots and the potatoes to the

tomato broth and meatballs. Cover and cook for an additional half

hour. When I made the albóndigas this time, I cubed the vegetables. I think the finished dish is more attractive with the vegetables cut into sticks.

The rich fragrance of the cooking albóndigas and their broth penetrates every corner of our home. By the time they're ready to eat, we are more than eager!

Albóndigas de Jalisco

served with steamed white rice (you might also like to try them with

Mexican red rice), sliced avocado, and fresh, hot tortillas. This flat

soup plate filled with albóndigas and vegetables needs more

sauce; we prefer to eat them when they're very soupy. A serving of rice

topped with three meatballs plus vegetables and sauce is plenty.

Albóndigas freeze really well, so I often double the recipe;

I use a flat styrofoam meat tray from the supermarket to freeze the

uncooked meatballs individually, then prepare the sauce, thaw the

meatballs, and cook them as described.

The single recipe serves eight.

Provecho!

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.