On October 4, 5, and 6, 2013, the Encuentro de Cocina Tradicional de Michoacán celebrates its 10th anniversary. In honor of the coming festival,

for the next three weeks Mexico Cooks! will publish its articles

about the most recent three years of the Encuentro. In mid-October, you'll find the report of the 10th Anniversary Encuentro,

right here on Mexico Cooks!.

At the 9th Annual Festival of Traditional Michoacán Cooking (October 19-21, 2012), Mexico Cooks! photographed alcatraces (calla lilies), an ear of blue corn, and a basketful of hypomyces lactifluorum, known in English as lobster mushroom and in Spanish as trompa de puerco (pig's

nose). During Michoacán's rainy season, the mushrooms grow wild and are

harvested in the pine forests around Lake Pátzcuaro. The lilies grow

in home gardens. Point of interest: Alcatraz, the ominous sounding name

of the infamous California prison, simply means calla lily.

For the last six years, Mexico Cooks!

has been a proud part of a uniquely Michoacán food festival. This

Encuentro de Cocina Tradicional de Michoacán was the impetus and the

paradigm for which in 2010 UNESCO awarded Mexico's food Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity

status. Every year, we feature stories and photos about the food that

makes this festival an inimitable part of Mexico's richness. Those

stories are here: Fourth Annual Encuentro, Fifth Annual Encuentro, Sixth Annual Encuentro, Seventh Annual Encuentro, and Eighth Annual Encuentro.

A huge bunch of freshly cut flor de calabaza

(squash flowers), used in a variety of Michoacán's regional dishes.

Did you know that only the male flowers are cut for cooking? The female

flowers are left to develop into squash on the vines.

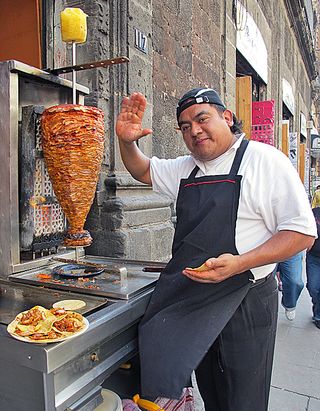

If asked about pre-Spanish conquest regional food, few people would think of

frogs. These great big frogs, for sale at Morelia's Mercado de

Independencia on the Sunday of the Encuentro, are caught around Lake Pátzcuaro and skinned for traditional preparations. Only the ancas de rana (frog legs) are eaten.

This year, rather than focus primarily on festival food, Mexico Cooks!

wants to introduce you to some of the now-elderly masters of

Michoacán's regional home cooking, women who have annually brought the

best of their family kitchens to the fair, who have proudly participated

in the festivals, and who have given their hands, hearts, and hearths

to the rescue and preservation of Michoacán's ingredients and

techniques.

Doña Paulita Alfaro Águilar lives in Nuevo San Juan Parangaricutiro, Michoacán. She has participated in all of the Encuentros

to date and has long operated her own restaurant. We chatted for a

while this year; she told me she thinks this might be her last Encuentro.

She told me that she is over 85 years old now and that in the last few

months, her health has begun to be less trustworthy. "I've had to go to

doctors a lot lately. And I don't feel as strong as I used to. See, I

have to walk with a cane." When it was time to say our farewells, she

added, "If I don't see you again next year, tell everyone I'm glad to

know that so many people tasted my food."

Update from the 10th Anniversary Edition of the Encuentro de Cocina Tradicional de Michoacán: Mexico Cooks! is sad to report that Sra. Paulita Alfaro Aguilar passed away during the course of the last year. QEPD (rest in peace), querida Paulita, your presence is everywhere on the Encuentro grounds. You leave an unfillable hole in our hearts.

Doña Matilde Apolinar Hernández from Charapan, Michoacán. Doña Matilde, who is also over 85 years old, prepared atápakua de queso (cheese in an herb-based sauce), atápakua de charales (tiny whole fish in an herb-based sauce), churipo (Purépecha beef soup), and atápakua de frijol (beans in an herb-based sauce) as well as corundas (Michoacán-style unfilled tamales). She participated in the the 2012 competitions with atápakua verde (a green herb-based sauce).

Doña Celia Moncitar Pulido shows us with her expressive hands one of the four elements of the Purépecha kitchen altar. The mazorcas (dried ears of corn) and beans represent Mother Earth, who gives us our food. Purépecha cooking–and eating–depend as much on spiritual elements as on earthly elements.

Doña Amparo Cervantes, legendary cook from Tzurumútaro, Michoacán. The 2011 Encuentro named Doña Amparo one of a handful of official maestras of the annual festival. The small group of recognized maestras had won the Encuentro

competitions so often–really, every year–that the organizing

committee retired these fabulous cooks from competition. Nonetheless,

at nearly 90, Doña Amparo continued to cook (but not compete) at the 2012 Encuentro. In addition to her participation at the Morelia event, she has also been an impetus and support for the cocina comunitaria (community kitchen) in Tzurumútaro, her hometown. A few of her specialties are mole with chicken and rice, pork with strips of chile poblano, corundas, and uchepos.

Doña Ana María Gutiérrez Águilar and her husband, don Espiridión Chávez Toral, who live in Calzontzin, in the municipality of Uruapan. At the 2012 Encuentro, I sat near the couple as we listened to a young and extremely talented woman sing a traditional Purépecha pirekua. When the song was over, Doña Ana María asked the singer who wrote the song. The singer mentioned a name. Doña Ana María stood up and said, "No señor! That song was written by my father, Valentín Gutiérrez Toral from Paricutín. He was too poor to afford to have his pirekuas

registered and most of them have been stolen. I've sung them all my

life, just as he taught them to me." The young singer invited Doña Ana María to the stage, where she sang her father's song a capella and wowed the crowd.

Doña

Lupita works selling onions at Morelia's Mercado de Independencia. At

more than 85 years old, she continues to accompany her slightly younger

sister to work. When asked how much longer she hopes to be at the

market, she smiled and merely shrugged. "Hasta que Dios me de licencia." ('As long as God lets me.')

These beautiful and highly respected old women will not be with us

forever. It's far better to honor them while they are still with us

than to carry flowers to them after they have gone.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.