Today's article is the continuation of Mexico Cooks!' report about the Eleventh Encuentro de Cocineras Tradicionales de Michoacán that took place April 3, 4, and 5, 2014. If you haven't had the chance to look at the May 10, 2014 article about the festival, you might like to jump back a week and read it, too.

The focus of Mexico Cooks!' articles about Michoacán's early April 2014 festival of 'las cocineras' (the cooks) is the presentations given by some of the Purépecha participants, as well as other talks given by professionals in Mexico's culinary and cultural worlds.

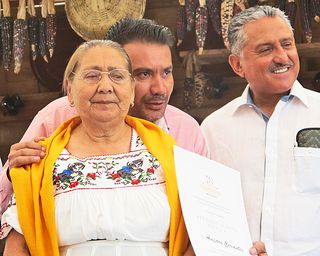

Maestra cocinera (master cook) Cecilia Bernabé Constancio, from San Lorenzo, Michoacán, receives her official recognition after giving a talk about how Purépecha women cure (prepare for cooking) clay pots. She told her audience that she learned to cure clay pots from her mother, who learned from her mother before her.

The entrance to San Lorenzo, Michoacán, where both Benedicta Alejo Vargas and Ceci Bernabé live and cook. Click to enlarge the image for a better view. Photo courtesy Panoramio.

Maestra Ceci Bernabé explained that when a woman buys a new olla or cazuela (two types of clay cooking pots), she first puts water in her new pot and puts it on the wood fire at home. If the pot can withstand a full rolling boil for 20 minutes and not break, it's good enough to use for cooking.

Demonstration setup of a new cazuela (shallow cooking dish), coated with cal (builder's lime) paste and ready to be cured. The cazuela is sitting in an anafre (a kind of brazier). The firebox is inside the square metal box under the brazier; the black rectangle is its opening. Unfortunately (or fortunately!) no one was allowed to have a fire under the canvas roof where the audience was seated. If you click on the photo to enlarge it, it is easier to see the thick cal paste.

Maestra Ceci told us that after she smears the cal paste thickly on the outside of the new pot, she asks the fire's permission to cure the cazuela. She then places the pot in the fire and leaves it for 20 to 30 minutes, long enough for the cal paste to harden and burn. She then removes the pot from the heat, cools it, and brushes off the cal. The pot is then ready for use.

Whole fish frying in a well-used cazuela. Foreigners sometimes buy these clay pots as souvenirs and are nervous about using them on a gas stove. Remember that the heat of the wood-fired kiln where the pot was made is higher than the heat of your stove. Try it, the clay gives a flavor depth to your food that metal can't offer. A clay pot that is glazed like this one, without colorful paint, contains no lead.

Newly made wooden cooking utensils like these, made of Michoacán pine, also need to be cured prior to using. Otherwise their strong pine scent can leach into the food you are preparing. Although you will see recommendations on the Internet for sanding your utensils and then curing them with oil, Doña Ceci uses a thin mix of cal and water. She places new utensils in the mix and heats them for several minutes, then washes the cal away with clean water.

After giving us these instructions, Maestra Ceci talked to her audience about her early life. She recalled, "I often talked to my abuelo (grandfather) about our ancient Purépecha history. In time, I came to realize that the Earth is my mother, and that all of her elements–air, fire, earth, and water–are necessary to life and worthy of respect. Without them, we don't exist.

"Our traditional diet is very healthy and all natural. Our cooking comes from our ancestors. My grandfather told me that the cabildos (town officials) ate first from the table, ate fish and other meats, and that the rest of us ate with or without meat, depending on what we had. During Lent and especially on Good Friday, we eat a lot of nopales (cactus paddles). The spines of the cactus paddles represent our people in mourning."

A plate of freshly fried charales, small freshwater fish that are fried whole in a cazuela and eaten during Lent and the rest of the year as well.

Maestra cocinera Antonina González Leandro holds a platter of fried uarhashi, the root of the chayote plant. Nothing in the Purépecha kitchen is wasted. After chayote is harvested, its roots are dug up and cooked. The root is a Lenten delicacy in the Purépecha kitchen. It certainly was! Maestra Antonina gave me a small slice to taste; later I ordered a plateful, served in a sauce of tomato and nopales. The Purépecha name of this delicious dish is uarhashi apopurhi.

Next week: Part Three of the Encuentro de Cocineras Tradicionales de Michoacán. We'll be spending time with copper artist Ana Pellicer and with jefe de cocina Yuri de Gortari and historian Edmundo Escamilla. Don't miss their fascinating points of view.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.