The area around Lake Pátzcuaro, in the state of Michoacán, bursts into wildflower bloom in late September, just as the rainy season is ending here. The flowers are naturalized wild cosmos, known here as mirasoles ("look-at-the-sun"). Entire fields fill with swaths of these delicate flowers, turning our green countryside into a temporary sea of pink. Behind the mirasoles is a milpa, a field of native Michoacán corn, beans, and squash.

These beautiful blossoms, selling now at the municipal market in Pátzcuaro, are called estrellas del campo (stars of the field). From the tops of the flowers to the bottom of their thin, tender stems, they measure about two and a half feet long. Each multi-petaled bloom measure about 1.5" in diameter. I've lived in Michoacán for a long time, but this is the first year I've seen these for sale. We took three large bunches as a gift to a friend–at 15 pesos the bunch. The total for a big armful of beauty was the Mexican peso equivalent of about $2.25 USD.

Available throughout the year, the native Mexican nanche fruit is in full-blown season right now, piled high on stands around the perimeter of the Pátzcuaro municipal market and on numerous street corners all over the town. Sold in clear plastic cups (as seen in the photo, courtesy of Healthline) or by the plastic bagful, the vendor will slather these 3/4" inch diameter fruits with jugo de limón (fresh-squeezed Key lime juice), a big sprinkle of salt, and as much highly spicy bottled salsa as your mouth can handle. The biological name of the nanche is Byrsonima crassifolia. The fruit is slightly sweet and mildly musty-flavored, a combination that most people love and that I regret to say is not a taste I enjoy at all. Nanches are packed with nourishment, though–a half-cup of them will give you nearly 60% of your daily Vitamin C requirement, 41 calories, and only 9.5 grams of carbohydrates!

These are jocotes (native Mexican plums), also in season now in central Mexico. The fruit measures about two to three inches long; the flesh is either bright orange or deep red, and the flavor is marvelous. Unfortunately the stone of this plum is almost as big as the entire fruit, and although you could eat it out of hand, the delicious jocote is most often made into an agua fresca (fresh fruit water) that is only available during the fruit's short season. This little plum is replete with Vitamins A and C, phosphorous, iron, and calcium, and is said to work wonders with gum problems.

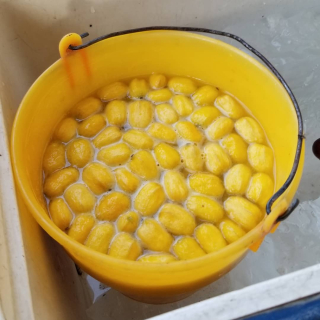

A bucket of freshly made agua fresca de jocote, with whole peeled plums floating on top. It's my favorite agua fresca, and only available when these plums are in season: right now!

Who wants to take a guess at what each of the green herbs (and the vegetable) is? The elotes (tender fresh Pátzcuaro red corn) at the bottom of the photo were part of a small daily harvest brought to sell on the outdoor periphery of Pátzcuaro's market. Just to the left of the corn, at the bottom of the photo, are some mint branches that the same vendor brought for sale. But above the mint? Click on the photo to enlarge it and you'll be able to tell that these are home-grown spiny chayotes. You are probably familiar with the paler green smooth-skinned chayotes (mirliton in Louisiana, pear squash in other English-speaking locations). The chayote has an interesting growing habit: unlike most squash, which grows as a vine along the ground, the chayote is airborne–its vines grow on overhead trellises and remind me of grapevines; the small squash hangs down from the vines. It's an extremely versatile vegetable, taking on the flavors of what you cook it with. Be sure to eat the soft, tender, flat, white seed–it's considered to be the prize part and is as delicious as the chayote itself.

To the right of the chayotes is a big bunch of wild anise, known in Pátzcuaro as anisillo. Used to make the Pátzcuaro regional specialty atole de grano, this herb is tremendously flavorful. In case you find some anisillo where you are, here's a recipe for atole de grano.

Atole de Grano

(Fresh Anise-Flavored Corn Kernel Soup)

Ingredients

2 fresh ears of tender young corn

2 cups fresh corn, cut from the cob

1 bunch wild anisillo

3 liters water

2 whole chiles perón (or substitute chiles poblano)

1/2 pound recently ground corn masa (dough)–ask at the tortillería near you

Salt to taste

Garnishes

1/2 medium white onion, minced

Chile serrano or chile perón, minced

Fresh Key limes, cut in half

Sea salt

Preparation

1. Clean the ears of corn, remove the silk and cut off the ends. Cut each ear into three pieces.

2. Boil the corn on the cob AND the corn kernels in enough water, for an hour and a half or until the corn is

tender.

3. Cut the stem away from the chiles, take out the seeds and veins. Cut the chiles into smallish pieces, ready to be whizzed in the blender.

4. In the blender, liquify the chiles, the anisillo, and the masa with two cups of water. Strain and add to the pot where the corn on the cob is cooking.

5. Allow to boil gently for about 10 to 15 minutes, until the liquid is slightly thickened.

To serve

1. Place sections of the cooked corn ears into bowls.

2. Ladle soup and corn kernels into the bowls.

3. Serve with the minced onion, minced chile to taste, sea salt, and Key lime halves to squeeze into the soup.

Serves 2 people as a main dish, 3 as a first course. This soup is both vegetarian and vegan, and gluten-free.

Atole de grano, made in a cazo (large copper kettle).

The vendor at this small booth at the Pátzcuaro market had an interesting variety of things for sale. Bottom right are fresh guavas, just now coming into season. To the left of the guavas are chiles perón (aka chiles manzano), arguably the most-used chile in this part of Michoacán. Above the chiles perón are fresh, green chiles de árbol. To the right are wild mushrooms known as patita de pájaro (little bird foot). These mushrooms, growing wild in Michoacán's woods and foraged during the rainy season, make a wonderful mushroom soup.

These are home-grown loquats, known in Mexico as nísperos (NEE-speh-rohs). Nísperos are local and are plentiful in markets right now.

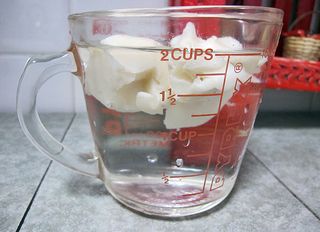

Gelatin–this large cupful is called "mosaíco"–mosaic, because of its many colored cubes. More gelatin is eaten in Mexico than in any other country of the world! A cupful this size is usually an eat-while-you-walk snack food. This one was made and sold from a tiny cart with no name, just to one side of the Pátzcuaro market. The young woman selling the gelatins said her name was Yesi–I said her cart was now dubbed Gelatinas Yesi, and she laughed.

Just at the corner of the market, we bumped into don Rafael, who was selling–you guessed it–cotton candy. Cotton candy HAS no season, it's always available here. Get the blue, it will turn your lips and tongue blue as a blueberry, but just for a while.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.