Mexico City residents currently ride the Metro, the Metrobus, and all other public transportation in surgical masks. (Photo courtesy Reuters.)

Mexico Cooks! was in

Mexico City from Thursday morning April 23 until Sunday night the 26th. I saw firsthand the start of the developing outbreak of a health emergency. The reality of what is essentially a government-mandated quarantine from the outbreak of la influenza porcina (swine flu) here in Mexico has been disastrous. On the one hand, people are sick and some have died of this flu. On the other hand, business closures have created economic havoc. And on the other hand (if you still have another hand free), tourists are staying away by the thousands.

In Mexico City, all museums

are closed, all cultural events are canceled, major religious celebrations are

prohibited, big sporting events are canceled or played behind locked doors with

no public in attendance. Movie theaters are dark. Bars and nightclubs are closed. All

restaurants are forbidden to offer table service–it's take-out only until

further notice.

On Friday afternoon at Superama in Morelia, only a few bags of frijol bayo remained on the shelves. Frijol negro (black beans), less commonly cooked here, were more plentiful.

Supermarket shelves are emptying fast; people are stockpiling

food with no knowledge when or even if it will be replenished. The government has ordered

that pregnant women and nursing mothers be allowed to stay home from work with

full pay and no penalty.

This block of Calle Sánchez Tapia, in Morelia's Centro Histórico, runs in front of the Conservatorio de las Rosas (the building to the left in the photo), the oldest music conservatory in the New World. Normally the street and sidewalks are clogged to the point of gridlock with cars and pedestrians. Mid-afternoon on Friday, the street was deserted save for a few parked cars and one young man walking in the shade.

Mexico City's streets are also empty. Last Sunday morning, I strolled

(STROLLED!) across Avenida de la Reforma, one of Mexico City's broadest and

busiest (and most beautiful) streets–no cars were out at all. All events and parades for May 1 (Labor

Day) were canceled, as were all events for Thursday's Día del Niño (Children's

Day).

Just a few packages of imported spaghetti remained on Superama's shelves, although some national brands are still plentiful. News sources report that spaghetti, bread, and milk are scarce in most supermarkets.

Friday afternoon even this elephant looked downhearted. Morelia's zoo, ordinarily crowded with children and adults, is closed until the flu situation passes. Mexico Cooks! snapped the photo from the sidewalk outside the zoo. Zoo employees were busy feeding animals and making small repairs.

Everywhere in the country, tourism is over, at least for the foreseeable future. All archeological sites in the

entire country are closed. Tour companies are canceling bookings for anywhere

in Mexico and redirecting the tours to other countries. Some airlines have refused

to land flights in the country. Friends who own B&Bs in various locations

are panicked–not for their own sakes, but for the sake of their employees. One

friend says that the last of her current B&B guests depart Mexico today (Saturday, May 2); after

that, she will be forced to close her two B&Bs until this crisis passes, as

every client who was to arrive during the coming weeks has canceled. She's devised a highly creative way to keep her employees working at least part-time, but their partial salaries will come out of her pocket, not out of B&B revenues.

Morelia-based Cinépolis is the largest movie theater chain in Mexico. All Cinépolis theaters in Mexico, as well as all of Mexico's other movie theaters, are closed by government mandate until May 6.

In the State of Jalisco, cruise ships have canceled several arrivals in

Puerto Vallarta and Guadalajara has canceled all Masses for this Sunday.

Restaurants are closed, tourist landmarks are closed, cultural events are

canceled. Businesses are losing hundreds of thousands of pesos every day of

this ongoing health crisis.

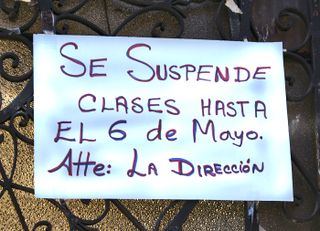

Everywhere in Mexico, all schools at all levels have been closed since Tuesday, April 28. The sign on this Morelia school gate reads, "Classes are suspended until May 6." Daycare centers are also closed.

In Morelia, where I live and where no cases of influenza porcina have been

reported (not that none exist; none have been reported), the streets are

silent. Where impossible daily traffic normally exists, few cars travel.

Schools are shuttered here, along with those in the entire country, until at

least May 6. Restaurants are closed; not all, but quite a few. Local tourist

destinations are closed. No Mass will be celebrated at local churches this

Sunday–people are invited to hear Mass via television or radio.

Normally illuminated by fireworks on Saturday nights and thronged with

believers for all Sunday Masses, Morelia's Cathedral will be shuttered

this Sunday (May 3). Mass will be celebrated a puerta cerrada (behind closed doors) and broadcast via television and radio. The stupendous photo is courtesy of my friend, Steven Miller. For a joyous look at his travels, see his photos on Flickr.

It seems to me that Mexican officials are reacting to the flu situation with

considerable calm and with well-reasoned actions–given the information that is

actually being disseminated to the public. Many informed sources (principally

physicians) are saying that the information in the media is deliberately cloudy

and inaccurate. They say that the death toll is actually enormously higher than

that which is in the news. Mexico Cooks! thinks that it is highly unlikely that

the government reaction (government and private business closures, prohibition

of large cultural and sports gatherings, suspension of Mass all over the

country) is an over-reaction. The societal and economic toll is too high to

take these measures were there no actual cause for doing so.

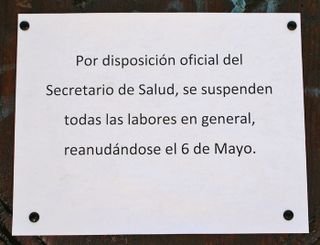

"By official disposition of the Secretary of Health, all work has been suspended, to begin again on May 6." This sign, tacked up on the door of the Conservatorio de las Rosas in Morelia, is repeated on business after business and school after school.

This is a holiday weekend in Mexico: Thursday was el Día del Niño,

Children's Day, a day of great festivity here. All concerts, festivals, and

other celebrations of the date were canceled. May 1 was el

Día del Trabajo, Labor Day, which is much more than the USA-style last-day-of-summer holiday here. ALL public demonstrations were canceled: none of the usual parades, speeches, and congregating of masses of people took place.

The butcher at Superama in Morelia said that although sales of pork meat have dropped a bit, he's glad it's selling at all. Many people erroneously think that la influenza porcina can be contracted through eating pork. It isn't true.

Wednesday night (April 29), Pres. Calderón spoke to the nation via television. He informed us

that all non-essential government business is canceled until May 6, that all

bars, nightclubs, spas, restaurants, etc, are ordered to close–it was in

essence a recap of all that has been closed or canceled up until now, with some

important additions. The nation is encouraged wherever possible to stay at home

for the next week. In his 10-minute or so speech, Calderón encouraged people to

be stoic until there is resolution to the flu situation. He assured the country

that Mexico has plenty of doctors and nurses, the most sophisticated testing

possible for this flu, and enough antiviral medicine to meet the heaviest need.

He reiterated the symptoms of the flu and the instructions for coughing into

the elbow, not greeting friends with a kiss, etc. At the end of the talk, said,

"Enjoy the company of your families, in your homes. Your home is the

safest place to be during this health situation." He actually sounded like

a primary school teacher–calm, cool, and matter-of-fact.

Economic recovery

will be slow for many and impossible for many. Small businesses, tour

companies, hotels, restaurants may well not recover, even after the flu is long

gone.

So: the bottom line is, no one knows the truth. Today I choose to believe that Mexico is correct to follow the World Health Organization's rules,

but being the skeptic and cynic that I am, there is a big niggle of doubt that

moves from the back of my mind to the front of my mind and again to the back of

my mind. As I always say, more will be revealed to you and to us…and

I pray that WHO is wrong.

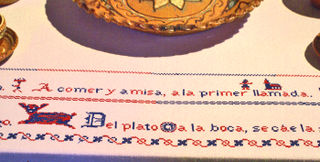

Mexico's sense of black humor will prevail. This just in:

This week–and this week only–Mexico Cooks! leaves its normal tour advertisement for another day.