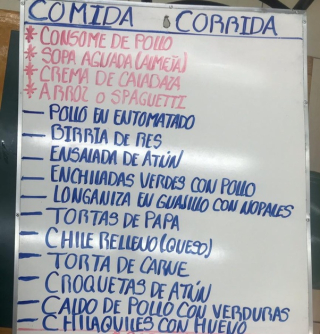

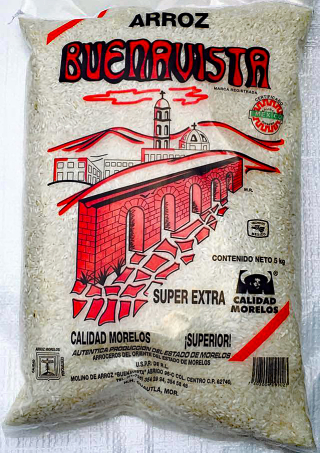

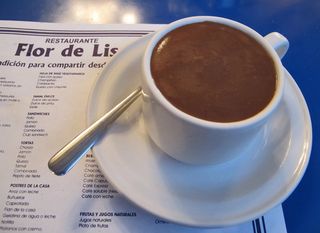

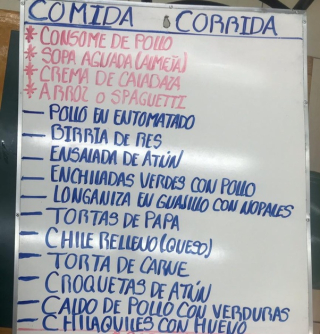

Last week, we talked extensively about sopa seca de arroz–Mexican 'dry soup' made of rice. Today, take a look at this menu from a fonda (a small, family-run restaurant) serving comida corrida in Mexico City. On the day this complete meal was offered, it included your choice of sopa aguada (liquid soup, either almejas (clam shaped pasta) soup or cream of calabaza), sopa seca de arroz (rice) OR sopa seca de spaguetti, and your choice of one of the items listed in blue, everything from pollo entomatado (chicken in tomato sauce) to longaniza sausage (similar to Mexican chorizo) and nopales (cactus paddles) in a guajillo chile sauce to chilaquiles con huevo (with eggs), and a huge number of other dishes!

A young butcher in Mexico City preparing longaniza. See the casing, on the tube to the left of his left hand? Book a tour with Mexico Cooks! and we can go watch him in person!

Today the topic is sopa seca de pasta–"dry soup" made of some kind of Mexican pasta–anything from standard spaghetti to elbow macaroni to some tiny special pastas created just for sopas, whether liquid or dry. Before I offer you a couple of recipes, here's a bit of the history of wheat (and pastas) in Mexico.

A Bit of the History of Wheat in Mexico

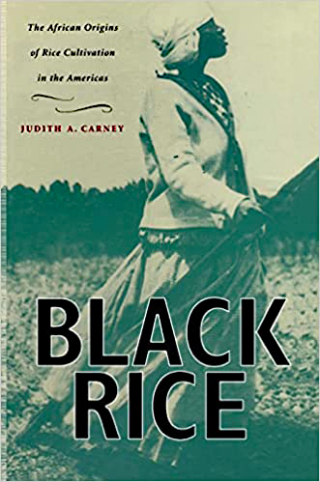

Like rice, wheat is not native to this country. It’s commonly said that wheat arrived—in large quantities–when the Spanish first arrived in the so-called New World. History tells the story of wheat in a different way. Unlike rice, wheat arrived almost by accident in what is now Mexico.

The voyages from Europe to what came to be called the Americas were long and arduous, and almost all edible provisions were eaten and depleted prior to the ships’ arrival. Apparently the voyagers weren’t concerned about keeping a few seeds to sow if and when they arrived. For that reason, wheat came to what is now Mexico a little later and by accident.

According to historians, three grains of wheat were found mixed into what was left of a 50 kilo (110 pound) bag of RICE, and were planted by a servant of Hernán Cortés. Just one of those three wheat grains germinated, and from that single plant, 180 grains of wheat were harvested and replanted. By 1534, only 13 years after the arrival of the Spanish, important harvests of wheat were being made near Texcoco and Puebla, in central Mexico.

The Spanish Jesuits subsequently carried wheat to the northern part of Mexico, where they taught the original peoples there to cultivate it, to harvest it, and to grind it into flour. The Spanish colonists were intent on converting the indigenous people to Catholicism, and according to Roman Catholic Canon Law (Canon 924, paragraph 2), pure wheat flour was then and continues to be required for the production of Communion hosts that were consumed by the Spanish colonists and by their indigenous converts.

The Spaniards also wanted the grain for the production of the white bread that they were accustomed to eating in Europe. That bread became a staple on the tables of the rich Spanish colonizers, while indigenous people continued to eat corn tortillas, as they had for thousands of years prior to the arrival of the Spanish.

A one-pound package of La Moderna brand durum wheat spaghetti. The Mexican pasta company La Moderna, founded in 1920, today offers more than 40 pasta shapes just for sopas, whether liquid or dry, in the tiny forms of bowties, gears, alphabet letters, tongues (shaped like tear drops), BBs, lentils, fideos, snail shape, clam shape, crowns, stars, mushrooms, petticoats, tiny elbow, little eyes, little hats, feathers, spirals, screws, and more! Packages of pasta for sopa weigh 200 grams and cost about 8 pesos (the equivalent in US dollars to about 40 cents). 200 grams of these pastas will feed about 3 to 4 people as the second course of a comida.

Pasta de fideo, also made of durum wheat. The size numbers of La Moderna fideo range from 0 (the thinnest) to 2 (the thickest). In Mexico, the second-most popular sopa seca de pasta is fideo, short, straight, thin pieces of pasta. Fideo is frequently also made into a liquid soup, caldo de fideo. We'll get to that in a few paragraphs!

In today's Mexico, the most popular ways to prepare sopa seca de pasta are:

1. Any shape pasta–especially fideo–cooked in caldillo, a thin red broth, until the broth is completely absorbed

2. Cooked pasta stirred into a cream sauce or a creamy tomato sauce and sprinkled with cheese

3. Hot spaghet

ti or elbow macaroni with cream and diced ham

4. Cold elbow macaroni salad

My personal favorite of the La Moderna line of tiny pastas: munición (literally, shot pellets) is the tiniest. Munición is the size and shape of BBs!

Very few nineteenth century post-independence Mexican culinary records include the consumption of various types of pasta: ravioles, macarrones (long noodles), and tallarines (long, flat noodles). Unless these were made in private homes, immigrants from countries where they were typically eaten brought them to Mexico. At the time of the Porfiriato (1876-1910), many things here were "Frenchified", as Porfirio Díaz was a francophile through and through. Italian-type pastas gave way to the French kitchen of elite, wealthy Mexicans.

Mexico Cooks! owns a reprinted Mexican cookbook, originally published in 1910, and has spent considerable time studying the recipes. That cookbook unfortunately offers no reference to pasta of any kind.

La Moderna was the first commercial pasta made in Mexico; its factory opened in 1920. There are are other pasta manufacturers in today’s Mexico, most notably La Italiana, with a factory in Puebla, founded also in 1920. La Italiana produces Italpasta for the Mexican market as does Golden Foods, located in Celaya, Guanajuato. In addition, foreign pasta makers have come to the Mexican market, particularly Barilla, which arrived in Mexico in 2003 and has its Mexico factory in San Luis Potosí. Barilla Mexico caters to the local market with both long and short pasta, plus five tiny pasta shapes specifically for preparing sopa seca.

La Moderna tiny coditos–wee elbow macaroni. These are size 1, the smallest made. Each little elbow measures about 1/2 inch long.

Forty-six percent of Mexico’s pasta is eaten at comida (Mexico's main meal of the day, eaten at mid-afternoon), either as a sopa seca or as a main dish. That’s 10 times more than we eat for supper, which is traditionally a lighter meal. The three most-eaten pastas in Mexico are spaghetti (generally spelled espagueti, according to the rules of Spanish pronunciation) at 29%, fideos, 24%, and coditos (all sizes of elbow macaroni from the tiniest ones to the largest), 15%–of the average family consumption of 12.7 kilos of pasta per year. That's about half the consumption of Italy, pretty amazing.

Are you ready for some recipes? I am, let's get cooking!

My favorite recipe for sopa seca de fideos is:

Sopa Seca (Dry Soup) of Fideos

1. 1 pound fresh ripe tomatoes, chopped

2. 1/4 of a medium-size onion, chopped

3. 1 large garlic clove

4. 1 chipotle chile en adobo (La Morena canned chiles, if you can find them. Otherwise buy a brand that's readily available.)

1.5 TBSP vegetable oil

1 200gr (7.5 oz) package of fine fideo pasta. If you can't find any brand of fideos, use broken-up angel hair pasta instead.

1.5 cups chicken broth

1/2 tsp oregano

Salt to taste

___________________________

Blend the first 4 ingredients in your blender until they are in small pieces, then add 1 cup of chicken broth and blend until the sauce is smooth.

Heat the oil in a medium-size skillet and then add the fideos. Fry until lightly browned, stirring often to avoid burning them. This step will take about 2-3 minutes. Remove the fideos from the skillet and reserve.

Add the caldillo, 1/2 cup of broth, oregano, and salt to taste to the skillet. Turn the heat up to bring to a boil (about 5 minutes). Once the sauce starts boiling, add the noodles, reduce heat to very low, and cover the skillet to let simmer.

Keep cooking for about 12-15 minutes, stirring occasionally as needed until noodles are cooked and tender. If the sauce still seems too liquid when the fideos are cooked through, simply remove the skillet from the heat and set aside for 5 minutes. This will allow the fideos to absorb the remaining liquid from the sauce.

Serve either family-style in a medium-size bowl or on individual small plates. Top with Mexican table cream or sour cream, crumbled sharp, dry white cheese and slices of just-ripe avocado.

Serves 4.

_________________________________________

The fideos, fried to a golden brown. This pasta is about an inch long and as thin as angel hair.

Caldo de Fideos

1 pound fresh ripe tomatoes, chopped

1/4 of a medium-size onion, chopped

2 large garlic cloves

1 cup water

Salt to taste

6 cups chicken broth, either home-made or purchased. I like Knorr, the broth in tetrapak, if you need to buy broth.

7.5 oz package of fideos

2 TBSP vegetable oil

3 sprigs fresh parsley

Put the tomato, onion, garlic and water into your blender jar and liquefy. When the tomato sauce is smooth, set it aside until you are ready to use it.

Put the lard or vegetable oil in a deep pot. Heat until it shimmers and add all of the fideos at once. Stir constantly over medium heat until the fideos take on a golden-brown color.

Pour the reserved tomato sauce through a wire strainer directly into the pot with the browned fideos. Allow to simmer (covered) on low to medium heat for about 5-10 minutes.

Uncover and add the parsley sprigs to the pot of simmering soup. Replace the cover and simmer for another 20 minutes.

Serves 4

This soup is delicious as a first course for a midday meal or for the main course of a light lunch. Photo courtesy Mexico10.org.

Serves 4 to 6.

_________________________________________

Strips of corn tortillas, fried to a crisp golden brown. I confess that I bought them already prepared!

And now for something completely different! This recipe, which I found recently, is for a sopa seca de tiritas de tortilla (thin, fried corn tortilla strips). It's not pasta, and it's not rice, and it is delicious! I particularly like the addition of hierbabuena (fresh mint) to the caldillo. Combined with the tomato broth and the corn tortilla strips, the flavors give you a big bang as a side dish or second course at your meal.

Sopa Seca de Tiritas de Tortillas de Maíz con Menta

Utensils you will need

A deep, heavy, covered frying pan

A large wooden spoon

Beautifully fresh home-grown hierbabuena (mint).

Ingredients

3-4 Tbsp freshly rendered lard or vegetable oil

1 medium-size onion, cut into half-moons

2 finely chopped tomatoes

3 cups beef broth, either home-made or purchased

6 big sprigs of fresh mint–leaves only, finely chopped

Approximately half a pound of fried, thin tortilla strips

Salt to taste

1/2 cup aged white cheese, grated. Look for Cotija-style cheese in your grocer's dairy case.

Fresh Roma tomatoes, ripe and delicious

Procedure

In a heavy skillet, heat the fat that you choose until it shimmers. Add the onion and sauté, stirring constantly, until it is translucent and slightly yellowish. Add the tomato and continue to cook until the tomato becomes soft and the majority of its juices have evaporated.

Add the beef broth and the finely chopped mint leaves and allow to simmer for several minutes, until the flavors have incorporated into the onion/tomato mix. Taste and add salt as necessary.

Add the fried corn tortilla strips and simmer until all the liquid has been absorbed, approximately 5 minutes.

Serve on individual small plate, topped with grated cheese, or serve family style on a platter and pass the cheese around to sprinkle thickly on each serving.

Finely chopped queso Cotija (Cotija cheese), ready to top your sopa seca de tiritas.

Serves 4.

Provecho! I hope you enjoy these truly home-style Mexican recipes. I look forward to seeing your comments.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.