Cochinita pibil from the Yucatán (seasoned pork, slow-cooked and then shredded), a specialty of Ricardo Muñoz Zurita's Restaurante Azul/Condesa. It's a quick route from the farm to the plate.

Mexico is one of the largest producers and consumers of pork in the world, second only to China. In spite of the 'swine flu' crisis several years ago, Mexico continues to eat pork at a record-breaking pace and, every year, to export millions of tons of pork to other countries. (FIRA)

From the growers' farms to a rastro (slaughterhouse) is a speedy ride along one of Mexico's super-highways. A truck like this one, loaded with pigs, is an everyday sight throughout Mexico. Photo courtesy ROTOV.

Mexico is not nearly as squeamish as the United States in seeing where its carne de cerdo (pork meat) comes from. In fact, a stroll through just about any city market or tianguis (street market) will give ample evidence that meat–including pork meat–comes from an animal, not from a sterile, platic-wrapped styrofoam meat tray at a supermarket.

Every part of the pig is used in Mexico's kitchens. The head is ordinarily used to make pozole, a rich stew of pork meat, reconstituted dried corn, spices, and condiments.

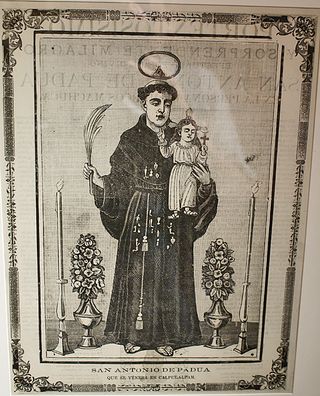

No pork existed in Mexico until after the Spanish conquest; in fact, no domestic animals other than the xoloitzcuintle dog were used for food. The only sources of animal protein were fish, frogs, and other water creatures, wild Muscovy-type ducks, the javalí (wild boar), about 200 varieties of edible insects, doves and the turkey, all native to what is now Mexico.

Mexico has been cooking head-to-tail since long before that notion came into international vogue. Pig tails are used here for roasting–look for recipes for rabo de cerdo asado (roast pig tail).|

No matter that just below these jolly mariachi pigs at Mexico City's Mercado de Jamaica, their once-live counterparts lie ready for the butcher's knife. These fellows play on!

Chicharrón (fried pig skin) is prepared fresh every day by butchers whose specialty is pork. Nothing goes to waste.

Just about any Mexican butcher worth his stripes can custom-cut whatever portion of the pig you need for meal preparation. In case you're not 100% familiar with the names of Mexican cuts, here are two pork cut charts, first in English and then in Spanish for comparison.

Pork cuts chart in English. Click to enlarge the image for better viewing.

Pork cuts chart in Spanish (for Mexican users). Even in Spanish, many cuts have different names depending on which country names them. Again, click to enlarge the image for a better view.

These suckling pigs were butchered at 6 weeks to 3 months old. Known in Mexico as lechón, roast suckling pig is a delicacy by any name. Many restaurants specialize in its preparation.

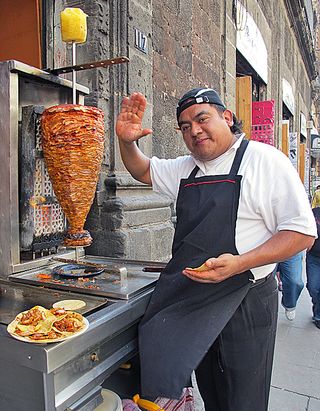

One of the most common and popular (and really delicious) kinds of street tacos is tacos al pastor (shepherd style tacos). Marinate thinly sliced pork meat in a sauce made of chiles guajillo, vinegar, and tomato. Next, layer the slices on a vertical spit so that they form the shape of a spinning top. At the top of the meat, place a pineapple without skin. Light the fire in the grate behind the spit and allow a portion of the meat to cook until slightly caramelized on the edges and tender within. Slice into very thin pieces, using them to fill a tortilla warmed on the flattop. With your sharp knife, flick a small section of the pineapple into the taco. Add the salsa you prefer, some minced onion and cilantro, and ahhhhh…the taste of Mexico!

Manitas de cerdo: pickled pigs' feet. The well-scrubbed feet are cooked in salted water, then added to vegetables cooked in a pickling solution of vinegar, chile, vegetables, and herbs. In Mexico, manitas de cerdo can be eaten as either a botana (snack) or a main dish.

One of my personal favorite pork dishes: carnitas from Michoacán! These carnitas in particular are the best I've ever eaten: large hunks of pork are boiled in lard until crispy on the outside, succulent and juicy on the inside. Chopped roughly and served with various salsas, they're the best tacos I know. Find them at Carnitas Aeropuerto, in Zamora, Michoacán.

Adobo huasteco, another deliciously spicy pork dish. It's been a while since this last appeared on our table–and it's high time we prepared it again. Click on the link for the recipe.

Last but not least, here's a rosy bouquet of pig heads for sale at the Mercado de Jamaica in Mexico City.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.