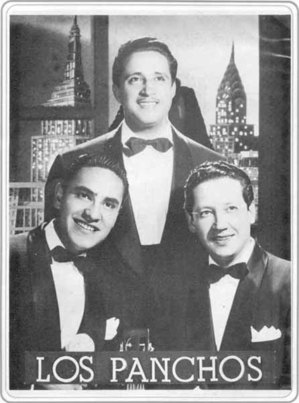

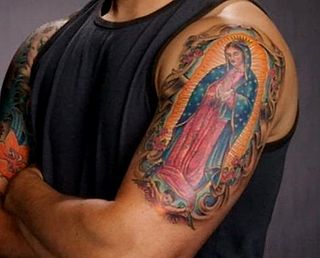

Trio Los Panchos, from the 1950s. They're still playing today and everyone of every age in Mexico knows all the words to all the songs they've sung since their beginning. You can hear them here:

[youtube=://www.youtube.com/watch?v=go8kmo4LABU&w=420&h=315]

A few nights ago some friends and I were having dinner at a local restaurant. A wonderful trio (lead guitar, second guitar, and bass) played a broad selection of Mexico's favorite tunes while we enjoyed our food and conversation. From the table behind us, a woman's voice rang out in English, "Boy, these mariachis are really good."

Her comment, one I've heard over and over again, made me think about the many varieties of Mexican music. Not all Mexican music is mariachi, although many people assume that it is.

It's just as incorrect to classify all Mexican music as mariachi as it is to classify all music from the United States as jazz. Mariachi has its traditions, its place, and its beauties, but there are many other styles of Mexican music to enjoy.

Ranchera, norteña, trio, bolero, banda, huasteco, huapango, trova, danzón, vals, cumbia, jarocho, salsa, son–??the list could go on and on. While many styles of music are featured in specific areas, others, like norteña, banda, ranchera, and bolero, are heard everywhere in Mexico. Let's take a look at just a few of the most popular styles of music heard in present-day Mexico.

Norteña

Música norteña (northern music) will set your feet a-tapping and will remind you of a jolly polka. Norteña had its beginnings along the Texas-Mexico border. It owes its unique quality to the instrument at its heart, the accordion. The accordion was introduced into either far southeastern Texas or the far north of Mexico by immigrants from Germany, Czechoslovakia, or Poland. No one knows for sure who brought the accordion, but by the 1950s this rollicking music had become one of the far and away favorite music styles of Mexico.

A norteña group of musicians playing a set of trap drums, a stand-up bass, and the accordion produces an instantly recognizable and completely infectious sound. The songs have a clean, spare accordion treble and a staccato effect from the drum, while the bass pounds out the deep bottom line of the music.

Música norteña is popular everywhere in Mexico. Conjuntos norteños (bands) often play as itinerant musicians. These are the musicians who are often hired to play serenades in the wee hours of Mother's Day morning, who play under the window of a romantic young man's girl friend while she peeps from behind the curtain, and who wander through restaurantes campestres (country-style restaurants) all over Mexico to play a song or two for hire at your table.

Here's a great norteño by one of my favorite groups, Bronco:

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=urH3cU2_z1M&w=560&h=315]

Banda de Viento and Banda

Banda de viento and banda are similar musical styles: both have a military legacy. Each has moved in its own direction to provide different types of entertainment. Banda de viento (wind band, or brass band) originated in Mexico in the middle 1800s during the reign of Emperor Maximilian and Empress Carlota. Later, Presidents Benito Juárez and Porfirio Díaz commissioned the creation of brass bands in their home state, Oaxaca, in imitation of the brass bands that entertained at the Emperor's court.

The huge upsurge of popularity of brass bands in Mexico came in the early 20th Century. After the Mexican revolution, local authorities formed "Sunday bands" made up of military musicians who played in municipalities' plaza bandstands all over Mexico.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_SlUY26dObo&w=560&h=315]

In Zacatecas, many bandas de viento specialize in leading callejonadas, street processions that exist for the joy of the music–if you're in Zacatecas, don't miss the fun!

Here's the Marcha de Zacatecas, one of Mexico's most famous marches:

[youtube=://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NWdB26F5wLQ&w=420&h=315]

There are regional differences in banda de viento style, but you can still take a Sunday stroll around many rural Mexican plazas to hear the tuba oompah the bass part, the trumpets blare, squeaky clarinets take the lead, and the tamborazo (percussion) keeps the beat. Sunday municipal band concerts no longer exist in some large cities, but you can still hear weekly concerts in smaller towns.

Banda music, which exploded onto the Mexican music scene in the 1990s, is a direct outgrowth of the municipal bands of Mexico. Banda is one of the most popular styles of dance music among Mexican young people. In small towns, we're often treated to a banda group playing for a weekend dance on the plaza or at a salón de eventos (events pavilion) in the center of the village. The music is inevitably loud, with a strong bass beat. You'll hear any number of rhythms, from traditional to those taken from foreign music. It's almost rock and roll. It's almost-well, it's almost a lot of styles, but it's pure banda.

Few foreigners go to these dances and that's a shame, because it's great fun to go and watch the kids dance. You might want to take earplugs; the banks of speakers can be enormous and powerful.

[youtube=://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KRlsmjY9gVY&w=420&h=315]

Banda El Recodo plays "El Sinaloense". Hang onto your hats!

The dancing will amaze you. Children, teenagers, and adults of all ages dance in styles ranging from old fuddy-duddy to la quebradita. La quebradita is a semi-scandalous style of dance which involves the man wrapping his arms completely around the woman while he puts his right leg between her two as they alternate feet and twirl around the dance floor. Complete with lots of dipping and other strenuous moves, la quebradita is a dance that's at once athletic and extremely sexual.

Bolero

In the United States and Canada, it's very common for those of us who are older to swoon over what we know as the 'standards'. Deep Purple, Red Sails in the Sunset, Smoke Gets in Your Eyes, and almost anything by Ol' Blue Eyes can take us right back to our youthful romances. Most of us can dance and sing along with every note and word.

Here in Mexico, it's the same for folks of every age. The romantic songs from the 1940s, 50s, and 60s are known as boleros. The theme of the bolero is love–happy love, unhappy love, unrequited love, indifference, but always love. I think just about everyone has heard the classic Bésame Mucho, a bolero written by Guadalajara native Consuelo Velásquez. This timeless favorite has been recorded by Frank Sinatra, Nat King Cole, and The Beatles, among countless other interpreters of romance.

Here's Luis Miguel, one of Mexico's modern interpreters of bolero, singing Bésame Mucho:

[youtube=://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wSO9P8LgC-o&w=560&h=315]

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_YJg0SpOoeQ&w=560&h=315]

Armando Manzanero, born in 1935 in Mérida, Mexico, was one of the most famous writers of bolero. His more than 400 songs have been translated into numerous languages. More than 50 of his songs have gained international recognition. Remember Perry Como singing It's Impossible? Armando Manzanero wrote it long ago as "Somos Novios".

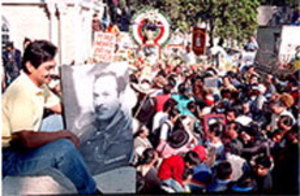

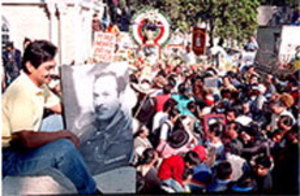

Crowds memorialize Pedro Infante, one of Mexico's greatest stars.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EdqLGTZd3NA&w=560&h=315]

"Amorcito Corazón" is one of Pedro Infante's his most famous songs. His voice–and the words to the song–make me sigh for joy.

Agustín Lara was another of Mexico's prolific songwriters. Before Lara died in 1973, he wrote more than 700 romantic songs. Some of those were translated into English and sung by North of the Border favorites Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra, and yes, even Elvis Presley. The most famous of his songs to be translated into English included You Belong to My Heart (originally Solamente Una Vez), Be Mine Tonight (originally Noche de Ronda), and The Nearness of You.

Ranchera

The dramatic ranchera (country music), which emerged during the Mexican Revolution, is considered by many to be the country's quintessential popular music genre. Sung to different beats, including the waltz and the bolero, its lyrics traditionally celebrate rural life, talk about unrequited love and tell of the struggles of Mexico's Everyman.

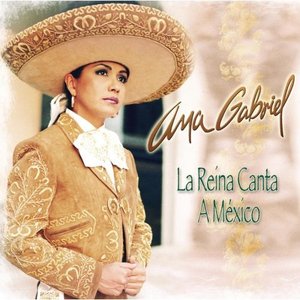

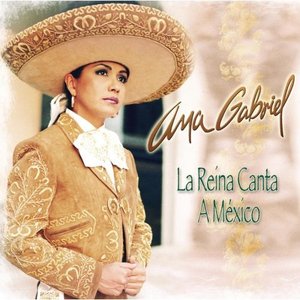

Ana Gabriel is one of today's reigning queens of música ranchera. Listen to her sing one of her all-time great songs: Y Aquí Estoy

Ranchera finds its inspiration in the traditional music that accompanies folkloric dancing in Mexico. Its form is romantic and its lyrics almost always tell a story, the kind of story we're used to in old-time country music in the United States: she stole my heart, she stole my truck, I wish I'd never met her, but I sure do love that gal. Pedro Infante, Mexico's most prolific male film star, is strongly associated with the ranchera style of Mexican music. One of the original singing cowboys, Infante's films continue to be re-issued both on tape and on DVD and his popularity in Mexico is as strong as it was in his heyday, the 1940s. Infante, who died in an airplane accident in 1957 when he was not quite forty, continues to be revered and is an enormous influence on Mexican popular culture.

Ranchera continues to be an overwhelmingly emotional favorite today; at any concert, most fans are able to sing along with every song. This marvelous music is truly the representation of the soul of Mexico, the symbol of a nation.

Ana Gabriel is the queen, but Vicente Fernández, who passed away on December 12, 2021, was the undisputed king of ranchera. Listen to him sing one of his classics: "Volver, Volver"

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JvBfxlg657I&w=560&h=315]

Don Vicente Fernández, whose ranch, huge charro ring and concert venue, huge restaurant, and large charro-goods store are located between the Guadalajara airport and Lake Chapala, was for years the reigning king of ranchera–indeed, he was considered by many to be the King of Mexico.

Mariachi

Mariachi really is the music that most folks think of when they think of Mexico's music. Mariachi originated here, it's most famous here, and it's most loved here. The love of mariachi has spread all over the world as non-Mexicans hear its joyous (and sometimes tragic) sounds. At this year's Encuentro Internacional del Mariachi (International Mariachi Festival) in Guadalajara, mariachis from France, Czechoslovakia, Canada, Switzerland and the United States (among others) played along with their Mexican counterparts.

In the complete mariachi group today there are six to eight violins, two or three trumpets and a guitar, all standard European instruments. There is also a higher-pitched, round-backed guitar called the vihuela, which, when strummed in the traditional manner gives the mariachi its typical rhythmic vitality. You'll also see a deep-voiced guitar called the guitarrón which serves as the bass of the ensemble. Sometimes you'll see a Mexican folk harp, which usually doubles the base line but also ornaments the melody. While these three instruments have European origins, in their present form they are strictly Mexican.

Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán is the most famous mariachi in the world. Every year in Guadalajara they honor the festival with their presence at the Encuentro Internacional de Mariachi. It's an unforgettable experience. Listen to them now, and watch the audience singing along:

[youtube=://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5_YLg7w4y9w&w=420&h=315]

The combined sound of these instruments makes the music unique. Like the serape (a type of long, brightly striped shawl worn mainly by Mexican men) in which widely contrasting colors are woven side by side–green and orange, red, yellow and blue–the mariachi use sharply contrasting sounds: the sweet sounds of the violins against the brilliance of the trumpets, and the deep sound of the guitarrón against the crisp, high voice of the vihuela; and the frequent shifting between syncopation and on-beat rhythm. The resulting sound is the musical heart and soul of Mexico.

One last video: you simply can't talk about Mexico's music without a deep bow to Juan Gabriel, one of the most beloved Mexican singers of all time. He first recorded the lovely Amor Eterno, written for his deceased mother, in 1991. It is a legendary classic. Once again, the audience sings along with every word.

[youtube=://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RgKqxLAhRKE&w=420&h=315]

Next time you go to your local music store, look on the racks of CDs for some of the artists and styles of Mexican music I've mentioned. You may be quite surprised to see how popular the different styles are in the United States and Canada. As the population of countries North of the Border becomes more Mexican, the many sounds of Mexican music follow the fans. Next thing you know, you'll be dancing la quebradita.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.