Most Mexicans eat traditional rosca de reyes (Three Kings' Bread) on January 6, the Feast of the Three Kings. Its usual accompaniment is chocolate caliente (hot chocolate). The rosca in the photo is normal size for a family–about 18" long.

This is the rosca monumental–humongous rosca–as served in Mexico City's Plaza de la Constitución (better known as the Zócalo). For the 2018 celebration, the rosca will contain 7,720 kilos of wheat flour, 2,000 kilos of sugar, 52,200 eggs (!), over 3,000 kilos of butter, 253 kilos of yeast, and all the rest of the ingredients necessary to accomplish a baking feat of this magnitude. Over 2,000 bakers and other personnel will participate in its preparation. Miguel Ángel Mancera, Mexico City's head of government, will once again preside over its slicing and serving–portions enough for approximately 250,000 hungry people.

One of the many Three Kings traditions in Mexico City is having one's photograph made with them, either just before or on their feast day. The photo above, taken at least 15 years ago in the city's Parque Alameda Sur, includes the Kings, some real live lambs, and (left to right), my friends Claire and Fabiola, and me.

The Día de los Reyes Magos (the Feast of the Three Kings) falls on January 6 each year. You might know the Christian feast day as Epiphany or as Little Christmas. The festivities celebrate the arrival of the Three Kings at Bethlehem to visit the newborn Baby Jesus. In some cultures, children receive gifts not on Christmas, but on the Feast of the Three Kings–and the Kings are the gift-givers, commemorating the gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh that they presented to the Baby Jesus. Many, many children in Mexico still receive special gifts of toys from the Reyes (Kings) on January

Typically, Mexican families celebrate the festival with a rosca de reyes (Three Kings' Bread). The size of the family's rosca varies according to the size of the family, but everybody gets a slice, from the littlest toddler to great-grandpa. Accompanied by a cup of chocolate caliente (hot chocolate), it's a great winter treat.

In this photo (click on it to enlarge it for a better view), the Reyes Magos arrive by boat in Cajititlán, Jalisco, where there is a large lake.

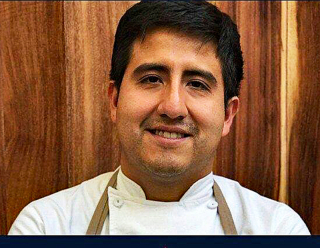

My friend, Chef Arturo Camacho Domínguez, recently wrote a bit for me about the significance of the rosca. He wrote, "The rosca de reyes represents a crown; the colorful fruits simulate the jewels which covered the crowns of the Holy Kings. The Kings themselves signify peace, love, and happiness. The Niño Dios hidden in the rosca reminds us of the moment when Saint Joseph and the Virgin Mary hid the Baby Jesus in order to save him from King Herod, who wanted to kill him. The three gifts that the Kings gave to the Niño Dios represent the Kings (gold), God (frankincense), and man (myrrh).

"In Mexico, we consider that an oval or ring shape represents the movement of the sun and that the Niño Dios represents the Child Jesus in his apparition as the Sun God. Others mention that the circular or oval form of the Rosca de Reyes, which has no beginning and no end, is a representation of the infinity of heaven–which of course is the home of the Niño Dios." Furthermore, the dried-fruit decoration (figs, ate [similar to fruit leather], and acitrón [candied cactus flesh]) represent the crowns of the Reyes Magos (the Three Wise Men).

The plastic muñequito (little doll) baked into my most recent rosca measured less than 2" tall. The figures were originally dried habas (fava beans), then were made of porcelain, but now they are generally made of plastic. See the tooth mark on the head? Mexico Cooks! is the culprit. Every rosca de reyes baked in Mexico contains at least one muñequito; larger roscas can hold two, three, or more. Mexico City's giant rosca normally contains 10,000 of these tiny figures.

Tamaleras (special pots to steam tamales) do extra duty on February 2–the Feast of la Candelaria, when literally millions of tamales are devoured at seasonal parties all over Mexico.

Tradition demands that the person who finds the niño in his or her slice of rosca is required to give a party on February 2, el Día de La Candelaria (Candlemas Day). The party for La Candelaria calls for tamales, more tamales, and their traditional companion, a rich atole flavored with vanilla, cinnamon, or chocolate. Several years ago, an old friend, in the throes of a family economic emergency, was a guest at his relatives' Three Kings party. He bit into the niño buried in his slice of rosca. Embarrassed that he couldn't shoulder the expense of the following month's Candelaria party, he gulped–literally–and swallowed the niño.

El Día de La Candelaria celebrates the presentation of Jesus in the Jewish temple, forty days after his birth. The traditions of La Candelaria encompass religious rituals of ancient Jews, of pre-hispanic rites indigenous to Mexico, of the Christian evangelization brought to Mexico by the Spanish, and of modern-day Catholicism.

In Mexico, you'll find a Niño Dios of any size for your home nacimiento (Nativity scene). Traditionally, the Niño Dios is passed down, along with his wardrobe of special clothing, from generation to generation in a single family.

The presentation of the child Jesus to the church is enormously important in Mexican Catholic life. February 2 marks the official end of the Christmas season, the day to put away the last of the holiday decorations. On February 2, the figure of Jesus is gently lifted from the home nacimiento (manger scene, or creche), dressed in new clothing, carried to the church, where he receives blessings and prayers. He is then carried home and rocked to sleep with tender lullabies, and carefully put away until the following year.

Each family dresses its Niño Dios according to its personal beliefs and traditions. Some figures are dressed in clothing representing a Catholic saint particularly venerated in a family; others are dressed in the clothing typically worn by the patron saints of different Mexican states. Some favorites are the Santo Niño de Atocha, venerated especially in Zacatecas; the Niño de Salud (Michoacán), the Santo Niño Doctor (Puebla), and, in Xochimilco (suburban Mexico City), the Niñopa (alternately spelled Niñopan or Niño-Pa).

This Xochimilco arch and the highly decorated street welcome the much-loved Niñopan figure.

The veneration of Xochimilco's beloved Niñopan follows centuries-old traditions. The figure has a different mayordomo every year; the mayordomo is the person in whose house the baby sleeps every night. Although the Niñopan (his name is a contraction of the words Niño Padre or Niño Patrón) travels from house to house, visiting his chosen hosts, he always returns to the mayordomo's house to spend the night. One resident put it this way: "When the day is beautiful and it's really hot, we take him out on the canals. In his special chalupita (little boat), he floats around all the chinampas (floating islands), wearing his little straw hat so that the heat won't bother him. Then we take him back to his mayordomo, who dresses our Niñopan in his little pajamas, sings him a lullaby, and puts him to sleep, saying, 'Get in your little bed, it's sleepy time!" Even though the Niñopan is always put properly to bed, folks in Xochimilco believe that he sneaks out of bed to play with his toys in the wee hours of the night.

Trajineras (decorated boats) ready to receive tourists line the canals in Xochimilco.

Although he is venerated in many Xochimilco houses during the course of every year, the Niñopan's major feast day is January 6. The annual celebration takes place in Xochimilco's church of St. Bernard of Sienna. On the feast of the Candelaria, fireworks, music, and dancers accompany the Niñopan as he processes through the streets of Xochimilco on his way to his presentation in the church.

Gloria in Xochimilco with Niñopa, February, 2008. Photo courtesy Colibrí.

Blue papel picado (cut paper decoration) floating in the deep-blue Xochimilco sky wishes the Niñopan welcome and wishes all of us Feliz Navidad.

El Día de La Candelaria means a joyful party with lots of tamales, coupled with devotion to the Niño Dios. For more about a tamalada (tamales-making party), look at this 2007 Mexico Cooks! article.

From the rosca de reyes on January 6 to the tamales on February 2, the old traditions continue in Mexico's 21st Century.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.