This week, Mexico Cooks! has once again cranked up the way-back machine for a trip down Memory Lane. This article, and the articles for the last two weeks, are from 2008. The Guadalajara newspaper El Mural asked me to give their reporter a food tour of Guadalajara "as if it were for tourists", and we had a fantastic time going places the reporter and the photographer had never been–in their own city. A short while after the tour, Mexico Cooks! was the big news on the first and subsequent pages of Buena Mesa, El Mural's food section. Here's the last part of the story of where we went and what we ate.

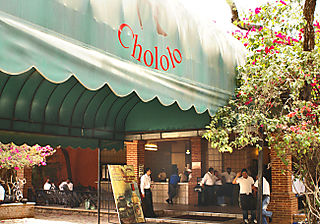

As you drive south of the Guadalajara airport, near the exit for El Salto, you'll see the green tile domes of Birriería Chololo on the west side of the highway. Be sure to stop!

One tiny part of the interior of Birriería Chololo Campestre. The restaurant seats up to 1000 people at a time.

Don Javier Torres Ruíz, grandson of Isidro Torres Hernández, made Birriería Chololo a Guadalajara icon. Don Isidro started the original business selling birria from his bicycle on the side of a street in .

Over 80 years ago, Birriería Chololo started life as a street stand, operated by . His grandson, Javier Torres Ruíz, made a huge success of the family business. Today, there are three Birrierías Chololo run by Don Javier's eight children, grandchildren, and other relatives and the Chololo campestre (countryside), managed by don Fidel Torres Ruiz, is the busiest of the batch. The restaurant, which seats 1000 people (yes, 1000) and turns the tables four times every Sunday, is closed only on the Fridays of Lent and on Christmas Day. Every other day of the year, it's a goat feast.

Birria and frijolitos refritos con queso, for two people. A bowl of consomé is in the background.

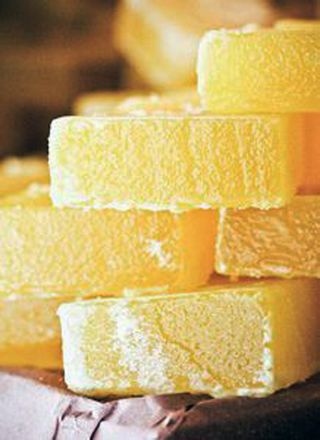

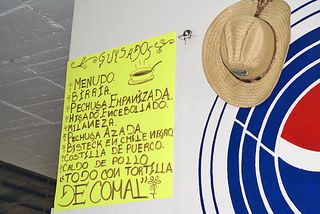

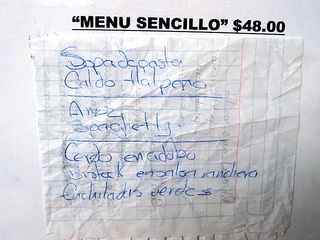

The offerings at Birriería Chololo (Chololo is a nickname for Isidro) are pure simplicity. Birria de chivo (goat), consomé (the rich goat broth), frijolitos con queso (refried beans with melted cheese), salsa de molcajete (house-made salsa served in heavy volcanic stone mortars), a quesadilla here and there, and a couple of desserts are the entire bill of fare. The birria, cooked 12 to 14 hours in a clay oven, is prepared to your order, according to the number in your party. You can ask for maciza (just chunks of meat) or surtido (an assortment of meats that includes the goat's tongue, lips, stomach, and tripitas (intestines).

Each order of birria is prepared at the time it's requested. The goat meat is chopped, weighed, mopped with sauce and glazed under the salamander, then brought piping hot to the table.

Birriería Chololo raises its own animals from birth to slaughter. That way, says the founder's nephew Fidel Torres Ruiz, quality control is absolute. The restaurant butchers approximately 700 100-pound animals per week to feed the hungry multitudes.

Salsa de molcajete estilo Chololo: addictive as sin and hotter than Hades. The salsa is served directly in the molcajete (volcanic stone grinding bowl).

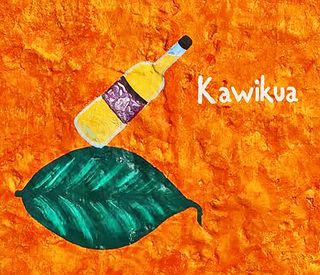

The full bar at Chololo serves its liquor in a way you might not have seen at your local watering hole. A bottle of your favorite tipple is set down on your table. A black mark on the open bottle's label indicates where your consumption starts, and at the end of your meal, you're charged for alcohol by the measure.

Consomé, birria, salsa de molcajete, and frijoles refritos con queso.

Some birrierías serve meat and consomé in one plate, but not El Chololo. Consomé, the heady pot likker rendered from the goats' overnight baking, is served in its own bowl. Before you dip your spoon into the soup, add some fresh minced onions, a pinch of sea salt, a squeeze of limón, and a squirt of the other house-made salsa de chile de árbol on the table, the one in the squeeze bottle. Ask for refills of consomé–they're on the house. Just don't ask for the recipe. It's a closely guarded 100-year-old family secret.

One of the two huge clay ovens for baking birria at Chololo. At Chololo, they take the time and care to prepare the birria with a marinade made of home-made red mole, oranges, and just a touch of chocolate, to add flavor to the meat. It also means fermenting their own pineapple vinegar to give additional flavor to the caldo.

On Sundays and other festive days, roving mariachis brighten up the restaurant's ambiance. Birthday parties, First Communion parties, wedding anniversaries, and other family fiestas are all celebrated at Chololo, and nothing makes a party better than a song or two. You'll hear Las Mañanitas (the traditional congratulatory song for every occasion) ten times on any given Sunday!

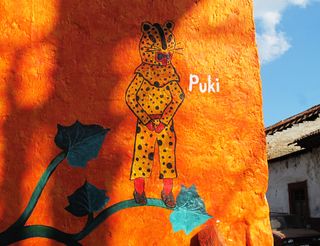

From the front door to the back garden, everything about Birriería Chololo is puro folklor mexicano and wonderfully picturesque.

Note: don Javier Torres Ruiz passed away on February 16, 2016. His family continues to maintain the 100-year-old tradition and quality at Birriería Chololo Campestre and at the restaurant's original location in Las Juntas, at the southern border of Guadalajara. "We're going to continue just as if he were still here," said don Fidel. And so they have.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.