Huge piñatas at a Mexico City market.

Among clean ollas de barro (clay pots), plastic receptacles filled with engrudo (flour/water paste), and colorful, neatly stacked rounds of papel de china (tissue paper), Sra. María Dolores Hernández (affectionately known as Doña Lolita) sits on an upturned bucket. Her birthday is on December 24, and she still lights up–just like a Christmas tree–when she talks about her business and her life.

The last point of the star-shaped piñata is in Doña Lolita's hands, nearly ready to be glued into place.

"When I was a young woman, raising my family together with my husband, it was hard for us to make a good living here in Morelia. We had eight children (one has died, but six girls and a boy survive) and we struggled to make ends meet. My husband was a master mason, but I wanted to help out with the finances. I knew a woman who made piñatas, and I thought, 'I can do that.' So I started trying my hand, over 60 years ago."

Doña Lolita adds another layer of newspaper to this piñata in progress. "You can't put too much newspaper on the pot, because it will take too long to break," she explained. "And you can't put too little on it, either, because then the first child to hit it will break it. That's no good, either. You just have to know how much to use." Click on the photo to enlarge it and get a good look at the clay pot inside the paper maché.

"The woman who made piñatas wouldn't give away her secrets, so I had to figure everything out for myself. You should have seen me the first time I tried to make a bird's beak for a parrot-shaped piñata! A man I knew told me to make it out of chapopote (a kind of tar), so I did. It hardened all right, but later in the day the weather warmed up and that beak dripped down to here! What a mess! I finally figured out how to make the shape out of paper, but I just about broke my head thinking about it!"

The family has cut rounds of papel de china (tissue paper) that wait to be glued onto a piñata. The black plastic bag holds strips of newspaper used for covering the clay pot to create the shape of the piñata.

Doña Lolita told me about the different grades of paper used to create different styles of decoration on the piñata, and she explained different kinds of paper-cutting techniques; she's absolutely the expert. Here, her son-in-law Fernando cuts tissue paper for fringe. His hands are so fast with the scissors it made my head spin; he can even cut without looking.

"In those days, the kind of clay pots we use for piñatas cost four and a half pesos for a gross–yes, for 144. In the old days, I usually sold about 7,000 piñatas every December, so you can imagine the investment I made just in clay pots. In the 1960s, I could sell a large piñata for seven pesos. Now–well, now the pots are much more expensive, so naturally the piñatas cost more, too. The large ones cost 45 pesos. This year, I'll sell about 1,000 piñatas just to break during the posadas. "

Piñatas in various stages of completion hang from every beam in Doña Lolita's tiny workshop.

"When my daughter Mercedes was about eight years old, she wanted to learn to make piñatas. She'd been watching me do it since she was born. So I taught her, and I've taught the whole family. Piñatería (making piñatas) is what's kept us going." Doña Lolita smiled hugely. "My children have always been extremely hard workers. There was a girl for each part of making the piñatas. Every year, we started making piñatas in August and finished at the beginning of January.

This gigantic piñata, still unfinished, measures almost six feet in diameter from point to point.

"One time, we had so many piñatas to finish that I didn't think we could do it. So I thought, 'if we work all night long, we can finish them by tomorrow morning.' Only I couldn't figure out how to keep the children awake to work all night." She laughed. "I went to the drugstore and bought pills to stay awake. I knew I could keep myself awake, but I gave one pill to each of the children. And in just a little while, I was working and they were sleeping, their heads fell right down into their work! What! Those pills didn't work at all! The next day I went back to the drugstore and asked the pharmacist about it. 'Oh no! I thought you asked me for pills to make them sleep!' he said." Doña Lolita laughed again. "We finished all the piñatas in spite of those pills, but you had better believe me, I never tried anything that foolish again."

Doña Lolita builds piñatas with her son-in-law, Fernando Cedeño Herrera (left), her daughter Mercedes Ayala Hernández, her grandchildren and her great-grandchildren. A close friend, Oswaldo Gutiérrez López (background), works with the family. Her grandson Enrique, 19, says he intends to keep the family business going.

Oswaldo Gutiérrez works on this piñata in the doorway of the tiny taller. Doña Lolita has taught many people the art of creating traditional piñatas, but her family and her loyal customers say she's the best piñatera (piñata maker) in Morelia.

"People come from everywhere to buy my piñatas. I don't have to take them out to sell; I only sell them here in the taller. Because they're so beautiful and well-made, all the best people in Morelia–and lots of people from other places–come to seek me out and order piñatas for their parties. I've taught my family that our work is our pride and our heritage, and my children have all taught their children the same. That is our legacy, our family tradition."

Fill the piñata with candy like these bags of traditional colación (hard candies especially for Christmas).

A group of Doña Lolita's piñatas, hung up for sale outside her workshop.

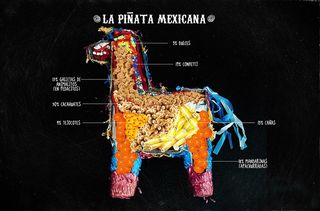

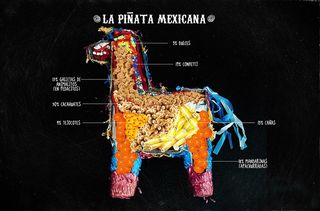

But why piñatas, and why in December? During the early days of the Spanish conquest, the piñata was used as a catechetical tool. The body of the piñata represented Satan; each of the seven points symbolized the seven capital sins (pride, lust, gluttony, rage, greed, laziness, and envy). Breaking the piñata equated with the triumph of good over evil, overpowering Satan, overcoming sin, and enjoying the delights of God's creation as they pour out of the piñata. Doña Lolita's most sought-after piñatas continue the traditional style, but she also creates piñatas shaped like roosters, peacocks, half-watermelons, deer, half moons, and once, an enormous octopus!

What the piñata might contain at Christmas–but fill it with whatever you think the kids will like best! Candies, small seasonal jícamas, sugar cane, mandarinas (tangerines) and cacahuates (fresh roasted in the shell peanuts, in season now) are all popular. Photo courtesy Google Images.

Now, for the nine nights from December 16 through December 24, Mexico celebrates las posadas. Each evening, a re-enactment of the Christmas story brings children dressed as la Virgencita María (ready to give birth to her baby) and her husband Sr. San José (and a street filled with angels, shepherds, and other costumed children) along the road to Bethlehem, searching for a place to stay. There is no place: Bethlehem's posadas (inns) are filled. Where will the baby be born! For the re-enactment, people wait behind closed doors at certain neighborhood houses. The santos peregrinos (holy pilgrims) knock, first at one door, then another. At each house, they sing a song, begging lodging for the night. At each house, the neighbors inside turn them away in song: 'No room here! Go away! Bother someone else!' Watch a lovely video filmed in Michoacán, a traditional small-town posada:

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XmdGZ0KXQ0Q&w=560&h=315]

I hope that one day you are able to participate in this beautiful tradition.

Freshly toasted cacahuates (peanuts) also stuff the piñata. The wooden box holding the peanuts is actually a measure, as is the oval metal box.

After several houses turn away la Virgen, San José, and their retinue, they finally receive welcome at the last, previously designated house. After the pilgrims sing their plea for a place to stay, the guests assembled inside sing their welcome, "Entren santos peregrinos…" (Come in, holy pilgrims…). The doors are flung open, everyone piles into the house, and a huge party starts. Traditional foods like ponche navideño (a hot fruit punch), buñuelos (a thin fried wheat dough covered with either sugar or syrup), and tamales (hundreds of tamales!) pour out of the kitchen as revelers sing villancicos (Mexican Christmas carols) and celebrate the coming of the Niño Dios (the Child Jesus). Finally, all the children line up to put on a blindfold and take swings at a piñata stuffed with candy, seasonal fruits, and peanuts.

This five-pound bag of hard candies shows a blindfolded (but peeking) boy ready to break open the filled piñata. Luis Gómez, a merchant at Local 290, Mercado Independencia in Morelia, offers these and other bags of piñata candies.

Mandarinas (tangerines) are in season at Christmastime and round out the goodies in many piñatas.

The piñata, stuffed with all it will hold, hangs from a rope during the posada party. A parent or neighbor swings it back and forth, up and down, as each child takes a turn at breaking it open with a big stick. Watch these adorable kids whack away at one:

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XIOjDz0smFw&w=420&h=315]

The piñata, lovely though it may be, is purely temporary. Nevertheless, happy memories of childhood posadas with family and friends last a lifetime.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here to see new information: Tours