A Christmas tree may be the central focus of your home decoration during this joyous season of the Christian year. In most parts of Mexico, though, the Christmas tree is a fairly recent import and the primary focus of the holiday is still on the nacimiento (manger scene, creche, or nativity scene).

One of Mexico Cooks!' biggest delights every late November and early December is shopping for Christmas–hunting for gifts of course, but also, on the lookout for new items to place in my nacimiento (manger scene). Truth be told, I have five nacimientos–or maybe six–that come out each Christmas season, but only one of them keeps growing every year.

The tiny figures in this nacimiento are made of clay; the choza (hut) is made of wood. The shepherds and angels have distinctive faces; no two are alike. One shepherd carries firewood, another a tray of pan dulce (sweet breads), a third has a little bird in his hands. The tallest figures measure only three inches high. According to la leyenda navideña (the Christmas legend), even the animals in the stable bowed down to worship the Niño Dios (Baby Jesus). Click on any photo to enlarge the image for a better view.

The Niño Dios is not placed in the pesebre (manger) until the night of December 24. The Niño Dios for the clay nacimiento above is just over an inch long and is portrayed sleeping on his stomach with his tiny knees drawn up under him, just like a real infant. This entire nacimiento was made about 35 years ago in Tonalá, Jalisco, Mexico.

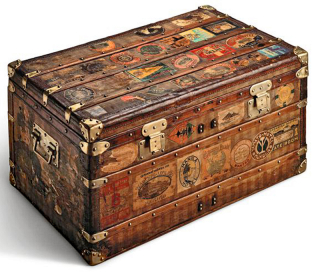

Mexican households traditionally pass the figures for their nacimientos down through the family; the figures begin to look a little tattered after traveling from great-great-grandparents to several subsequent generations, but no one minds. In fact, each figure holds loving family memories and is the precious repository of years of 'remember when…?''. No one cares that the Virgin Mary's gown is chipped around the hem or that St. Joseph is missing an arm; remembering how the years-ago newest baby, now 32 and with a baby of his own, teethed on the Virgin's dress or how a long-deceased visiting aunt's dog bit off St. Joseph's arm is cause for a family's nostalgic laughter.

Nacimiento en vivo (living nativity scene), Lake Chapala, Jalisco, Mexico. In 13th century Italy, St. Francis of Assisi was the first to be inspired to re-enact the birth of Christ. The first nacimiento was presented with living creatures: the oxen, the donkey, and the Holy Family. Even today in hundreds of Mexican communities, you'll see living manger scenes.

Holy Family, 18th century Italy. The earliest nativity figures, made of clay, were created in 15th century Naples and their use spread rapidly throughout Italy and Spain. In Spain, the early figural groups were called 'Belenes' (Bethlehems).

A few weeks before Christmas, my tiny nacimiento de plomo (manger scene with lead figures, none over four inches high) comes out of yearlong storage. The wee village houses are made of cardboard and hand-painted; each has snow on its roof and a little tree in front. You might well ask what the figures in the photo represent: Sr. San José (St. Joseph, who in Mexico always wears green and gold) leads the donkey carrying la Virgen María (the Virgin Mary) on their trek to Belén (Bethlehem). We put these figures out earliest and move them a bit closer to Bethlehem every day. This nacimiento is the one that grows each year; I have added many, many figures to the original few. This year the total number of figures is near 250.

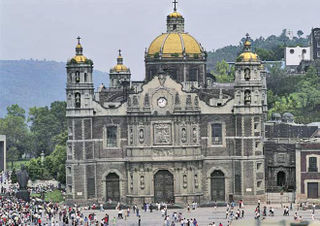

Click on this photo from the early years of my nacimiento and you will see that the Holy Family has not yet arrived in Bethlehem; the choza is empty and St. Joseph's staff is just barely visible in the lower right-hand corner. Click to enlarge the photo to better see the figures in the nacimiento: gamboling sheep, birds of all kinds, shepherds, shepherdesses, St. Charbel (to the left and behind the choza), an angel, and Our Lady of Guadalupe are all ready to receive the Niño Dios (Baby Jesus). Notice the upright red figure at the right, standing in the Spanish moss: that's Satanás (you know who!), who is always present in a Mexican nacimiento to remind us that although the birth of Jesus offers love and the possibility of redemption to the world, sin and evil are always present.

Detail of the lead figures in my ever-growing nacimiento. To the left is a well (with doves) and a woman coming to draw water; to the right is an arriero (donkey-herder) giving his stubborn little donkey what-for.

No matter how many figures are included in a manger scene, the central figures in any nacimiento are the Holy Family (St. Joseph, the Virgin Mary, and the Baby Jesus). In Mexico, those three are collectively known as el misterio (the mystery).

A very small portion of one of the largest nacimientos on display in Mexico City. It measures more than 700 square meters and includes thousands of figures. They include everything you can think of and some things that would never occur to you: a butcher shop, a running stream and a waterfall, sleeping peasants, and washerwomen. A nacimiento can include all of the important stories of the Bible, from Genesis to the Resurrection, as well as figures representing daily life–both today's life in Mexico and life at the time of Jesus's birth. Photo courtesy El Universal.

Papel roca (hand-painted paper for decorating a nacimiento), a choza (little hut), and two kinds of moss for sale in this booth at the Guadalajara tianguis navideño (Christmas market). Over the course of years, Mexico Cooks! has purchased figures of a miniature pre-Hispanic loinclothed warrior, a tiny shoemaker working at his bench, a wee man sawing firewood, and a shepherd standing under a tree while holding a lamb. The shepherd's tree looks exactly like a stalk of broccoli and makes me smile each time I look at it.

Where in Mexico can you buy figures for your nacimiento? Every city and town has a market where, for about a month between the end of November and the first week in January, a large number of vendors offer items especially for Christmas. Some larger cities, like Mexico City, Guadalajara, Morelia, and others, offer several tianguis navideños (Christmas markets) where literally thousands of figures of every size are for sale.

A few years ago, I found a tiny figure of the seated Virgin Mary, one breast partially exposed as she nurses the Niño Dios, who lies nestled in her arms. It's the only one like it that I have ever seen. She measures just about two and a half inches high.

This shepherd keeps watch over his cook-fire in the Mexico Cooks! nacimiento. He's about three inches long from head to toe; the base of the fire is about the same length; the lead props for the pot are about two inches high.

This booth at a tianguis navideño in Guadalajara offers Niños Dios in every possible size, from tiny ones measuring less than three inches long to babies the size of a two-year-old child. In Mexico City's Centro Histórico, Calle Talavera is an entire street devoted to shops specializing in clothing for your Niño Dios. The nacimiento is traditionally displayed until February 2 (Candlemas Day), when the Niño Dios is gently taken out of the pesebre (manger) in a special ceremony called the levantamiento (raising). The nacimiento is then carefully stored away until the following December.

The choza (hut) in the Mexico Cooks! nacimiento. People and animals are waiting for the arrival of the Mary and Joseph, and for the birth of the Christ Child. Click on any photo for a larger view. In addition to the original lead figures, we now have indigenous figures found in a Mexico City flea market, antique lead animal figures (the rabbit behind the sleeping lamb, the little brown dog behind the kneeling shepherd), finely detailed santons from a trip to Provence, modern resin figures of every description, and many more. Two hundred more–and counting!

Piles of gold and silver glitter cardboard stars of Bethlehem, for sale at the tianguis navideño in southern Mexico City's Mercado Mixcoac.

At another tianguis navideño, an assortment of clay figures for your nacimiento: villagers, chickens, and vendors. Size and scale don't matter: you'll find crocodiles the size of a soft drink can and elephants no bigger than your little finger. Both will work equally well in your nacimiento.

Giant flamingos go right along with burritas (little donkeys). Why not?

Each traditional figure in a nacimiento is symbolic of a particular value. For example, the choza (the little hut) represents humility and simplicity. Moss represents humility–it's something that everyone steps on. The donkey represents the most humble animal in all creation, chosen to carry the pregnant Virgin Mary. The star of Bethlehem represents renewal and unending light.

Which diablito (little devil) tempts you most, the one with the money bag or the one with the booze?

How many shepherds do you want? This annual tianguis navideño booth has hundreds, and in sizes ranging from an inch to well over a foot tall.

It wouldn't be a Mexican nacimiento without tortillas! You wouldn't want the Sagrada Familia (Holy Family) to go hungry, would you?

Turkeys were a new addition for Navidad 2016: a dear friend knows my nacimiento passion and found this pair of antique turkeys for me. The bigger one is just 3" from beak to tail. They'll fit right in with the other 200-plus figures!

This Christmas, Mexico Cooks! wishes you all the blessings of the season. Whatever your faith, we hope you enjoy this peek at the nacimiento, one of Mexico's lasting traditions.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here to see new information: Tours