When we who know tamales think about Oaxaca-style tamales (and who here reading Mexico Cooks! doesn't know tamales?), this is what comes immediately to mind: a tamal oxaqueño like the one above, made from maíz nixtamalizado (in this case, corn prepared to make masa para tamales), filled with mole negro, mole amarillo, or another typical Oaxaca filling, wrapped in banana leaves, tied up, and steamed until ready to be devoured. Who knew that there were so many, many more traditional kinds of tamales from Oaxaca? Oaxaca is a state of eight regions, and each region has its tamales specialties, and oh boy! Get ready for thrills, chills, and corn-based excitement.

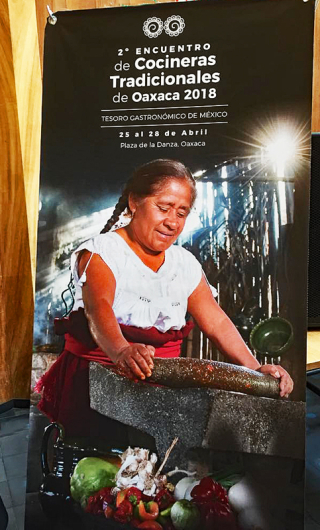

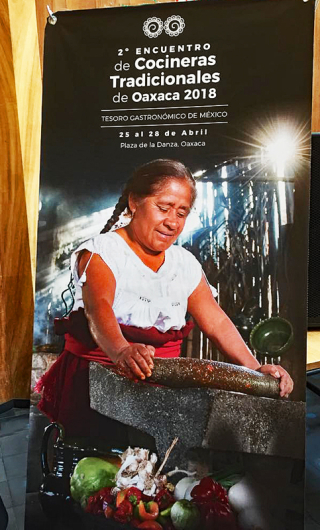

Early on the morning of April 28, 2018, the last day of the Encuentro de Cocineras Tradicionales de Oaxaca had an incredible treat in store for its attendees. In one large section of Oaxaca's centrally located Plaza de la Danza, all of the Encuentro's dining tables were squeezed tightly together to form several rows of demonstration stands. Seventy of the participating cocineras bustled about, each readying her space for the biggest tamales-making party I've ever seen. Each cook carefully made her mise en place–not that she would have called it that: having made tamales all her life, each cocinera knew in her bones just how to put her ingredients in exactly the place, exactly in the order, in which she needed them to be at hand.

A portion–just a small part–of the tamales demonstration. The crowd of attendees was so intensely packed and fascinated by what we were seeing, and the number of cocineras was so large, that it was difficult to make a plan to see all of them. Plus, the absolute beauty of so much living tradition playing out before my eyes caused me to continually wipe away tears of joy and gratitude that I was present. So moving…

Cocineras tradicionales in another section of the large demonstration space. The tamales resulting from the cocineras' preparations were later steamed and sold to the public. Right to left in the photo: cocineras tradicionales Sra. Gladys Hortencia Calvo García (in the white apron, preparing tamal pastel de carne) ; Sra. Rosario Cruz Cobos (tamales de masa cocida con costilla de puerco en hoja de pozol), (skip) and Sra. Emma Méndez García (tamal Nioti Nal'ma).

These are leaves from the almendro: the almond tree. Cocinera tradicional Sra. Raquel Silva Méndez from San Juan Bautista Cuicatlán (Zona Cañada) used them to wrap tamales de frijol.

Tamales de piedra (stone), which in fact are made with nixtamalize-d corn masa (dough) moistened with liquid from cooked black beans, formed on a base of leaves from aguacate nativo (native avocado trees), and then further wrapped in part of a banana plant trunk. In this photo, the jícara contains sea salt.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=47uS5jULjOc&w=560&h=315]

Watch Sra. Martina Sánchez Cruz, from San Juan Teitipac in Oaxaca's Valles Centrales, as she prepares tamales de piedra.

Here's the finished tamal de piedra, ready to be steamed. You can see the green avocado leaves poking out of the bundle; the aguacate nativo leaves add a slight anise flavor to these tamales. This tamal is one of the interesting types that I had never seen before attending the 2018 Encuentro de Cocineras Tradicionales de Oaxaca.

At the top, freshly rendered manteca de cerdo (pork lard). Below, home-made sausage for tamales de salchicha as prepared by cocinera tradicional Sra. Anel Felisa Hernández Morga, of Ejutla de Crespo (Zona Valles Centrales). This was another tamal new to me.

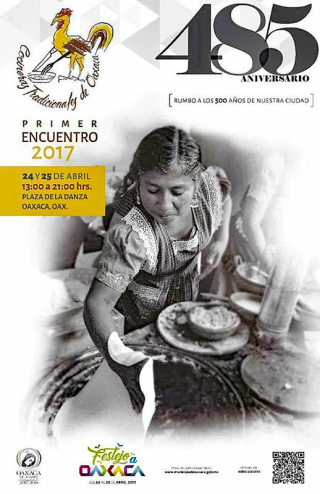

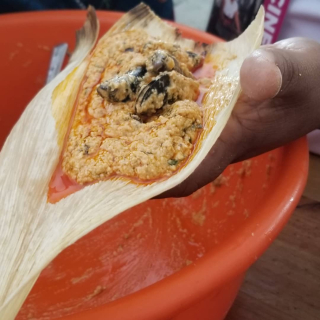

Another truly unusual Oaxacan tamal which I first tasted at the initial Encuentro de Cocineras Tradicionales in April 2017: tamal de tichinda, made with mejillones de agua dulce (sweet water mussels), incorporated shell and all into the nixtamalize-d corn masa (dough). These are wrapped in totomoxtle (dried and rehydrated corn husks) and then steamed; cocinera tradicional Sra. Brígida Martínez Ávila of Zapotalito, Tututepec (Zona Costa) is preparing these. Another variety is similarly made but is wrapped in banana leaves.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g2Usk_OOxYg&w=560&h=315]

Let's watch Sra. Martínez as she makes the tamales de tichinda. Notice that she fills one totomoxtle with the masa/tichinda mixture and then adds a second corn husk for further stability of the tamales. She sets them aside to be steamed later.

Tamales de tichinda, ready to be steamed. I dreamed about these delicious tamales for an entire year and was so thrilled to know that I could taste them again in 2018.

Expert hands making the initial folds of banana leaves, slightly warmed over a flame to make them soft and flexible, enclosing masa and a filling.

The second step of folding the banana leaves to enclose the masa and filling.

The final step: tying each bundle securely together with a strip of the same banana leaf.

Cocinera tradicional Sra. Elena Tapia Flores, who came from San Juan Colorado, Jamiltepec (Zona Costa) to prepare tamales de hierbabuena con pollo (tamales with mint and chicken) at the 2º Encuentro de Cocineras Tradicionales de Oaxaca.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i30BTCWyTsg&w=560&h=315]

Sra. Tapia kneads the masa for her tamales until it is the perfect consistency for spreading on rehydrated totomoxtle (dried, then rehydrated corn husks).

The prepared masa for Sra. Tapia's tamales de hierbabuena con pollo. The flecks that you see in the dough are hierbabuena (mint).

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yqunGQaayOM&w=560&h=315]

Cocinera tradicional Sra. Catalina Chávez Lucas from Tlacolula de Matamoros (Zona Valles Centrales) prepares tamales de conejo (rabbit tamales).

Ingredients for tamales de cambray oaxaqueños: banana leaf, nixtamalize-d masa, and a mixture of chicken, potatoes, raisins, almonds, and mole paste.

Tamales de cambray, the finished product. These are right up at the top of my "favorite tamales" list. They are slightly sweet, slightly savory, and in my opinion, just right.

Cocinera tradicional María del Carmen Gómez Martínez of the Sierra Norte, filling one of her tamales de mole amarillo (yellow mole).

See how María del Carmen's tamales are rolled up? I've never seen tamales made in this style before, have you?

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sS9TufA9mOY&w=560&h=315]

These two elderly women, both cocineras tradicionales, really touched my heart: they kept plugging away and made so many tamales together. Life's much more rewarding when we share its work and its joys, its sorrows and its happiness, with one another!

Mexico Cooks! and everyone I met or talked with had a fabulous time at the 2º Encuentro de Cocineras Tradicionales de Oaxaca, held April 25-28, 2018, in the city of Oaxaca. If any of you would be interested in attending all or part of this incredible festival with me in 2019, please let me know as soon as possible. I'd be glad to send you a quote for a tour, for all or part of this incredibly exciting event.

Meantime, come back next week for the start of the next leg of the Mexico Cooks!/Silvana Salcido Esparza of Barrio Café Phoenix fame to continue our tour of Oaxaca: next, we're going to the southernmost part of the state: the Isthmus of Tehuantepec! Here we go: first stop, the Sunday Market at Tlacolula, Oaxaca!

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.