Beautifully home-prepared chiles en nogada, as presented several years ago at a traditional food exhibition in Pátzcuaro, Michoacán.

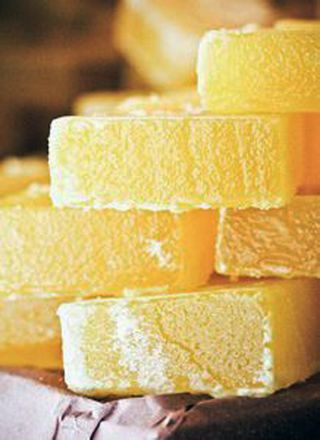

Freshly harvested and peeled nuez de castilla (walnuts), an essential for seasonal chiles en nogada.

Mexico celebrates its independence the entire month of September with parades, parties, and traditional food and drink, served in restaurants and at home. The traditional festive dish during the weeks just before and after the Independence Day holiday is chiles en nogada, a magnificent tribute to the seasonal availability of a certain kind of peach, the locally grown panochera apple, in-season granadas (pomegranates) and nuez de castilla (freshly harvested walnuts). From mid-July until early October, seasonal local fruits, fresh pomegranates, and newly harvested walnuts make chiles en nogada possible. Mildly spicy chiles poblano, stuffed with picadillo and topped with richly creamy walnut sauce and pomegranate seeds, flaunt the brilliant green, white and red of the Mexican flag.

The panochera apple, grown in the Mexican state of Puebla, and pera lechera (milky pear), also grown in the area, are two must-have ingredients for making chiles en nogada in Mexico. If you live outside Mexico, a small crisp apple and a very crisp pear (Bosque or d'Anjou) would substitute.

This festive dish is traditionally served on September 15 or 16 in honor of Mexico's Independence Day, though it is popular anytime in the late summer and fall. During August and September in the highlands of Mexico, particularly in Mexico City and Puebla, vendors wander tianguis (street markets) and other markets, selling the clean, white meats of nuez de castilla. It is important to use the freshest walnuts possible, as they produce such a creamy, rich sauce that it is worth the effort to buy them peeled or peel them oneself. Yes, the recipe is time-consuming…but you and your guests will jump up and shout "VIVA!" when they've licked the platters clean.

Ingredients

For the meat:

- 2 pounds beef brisket or other stew meat or 1 pound beef and 1 pound pork butt**

- 1 small white onion, quartered

- 2 large cloves garlic

- about 1 Tbsp sea salt

For the picadillo (filling):

- 4 Tbsp safflower or canola oil

- the shredded meat

- 1/3 cup chopped white onion

- 3 large cloves garlic, minced

- 1/2 tsp ground cinnamon

- 1/4 tsp freshly ground black pepper

- 1/8 tsp ground cloves

- pinch pimienta gorda (allspice)

- 1/2 plátano macho (plantain), chopped fine

- 1 or 2 chiles serrano, finely minced

- 4 Tbsp chopped fresh walnuts

- 4 Tbsp slivered blanched almonds

- 2 Tbsp finely diced biznaga (candied cactus, optional)

- 1 fresh pear, peeled and chopped

- 1 apple, peeled and chopped

- 4 ripe peaches, peeled and diced

- 3 Tbsp Mexican pink pine nuts. Don't substitute white if you aren't able to find pink. White pine nuts have a bitter aftertaste.

- 3 large, ripe tomatoes, roasted, peeled and chopped

- sea salt to taste

Fully mature chiles poblano, picked fresh and sold on the street in Tehuacán, Puebla.

Deep green chiles poblano are normally used for chiles en nogada. These measure as much as seven inches long. If you click on the photo to make it larger, you can see that these chiles have deep, long grooves running down their sides. When I'm buying them, I choose chiles poblano that are as smooth as possible on their flat sides. The smoothness makes them easier to roast easily.

For the chiles:

–6 fresh chiles poblanos, roasted, peeled, slit open, and seeded, leaving the stem intact

For the nogada (walnut sauce):

- 1 cup freshly harvested nuez de castilla (walnuts), peeled of all brown membrane**

- 6 ounces queso de cabra (goat cheese), queso doble crema or standard cream cheese (not fat free) at room temperature

- 1-1/2 cups crema mexicana or 1-1/4 cups sour cream thinned with milk

- about 1/2 tsp sea salt or to taste

- 1 Tbsp sugar

- 1/8 tsp ground cinnamon

- 1/4 cup dry sherry (optional)

**Please note that this recipe is correctly made with walnuts, not pecans. Using pecans will give your sauce a non-traditional flavor and a beige color, rather than pure white.

Remove the arils (seeds) from a pomegranate. We who live in Mexico are fortunate to find pomegranate seeds ready to use, sold in plastic cups.

For the garnish

–1 Tbsp chopped flat-leaf parsley

–1/2 cup fresh pomegranate seeds

Preparation:

Cut the meat into large chunks, removing any excess fat. Place the meat into a large Dutch oven with the onion, garlic, and salt. Cover with cold water and bring to a boil over medium-high heat. Skim off any foam that collects on the surface. Lower the heat and allow the water to simmer about 45 minutes, until the meat is just tender. Take the pot off the stove and let the meat cool in the broth. Remove the pieces of meat and finely shred them.

Candied biznaga (aka acitrón) cactus. Do try to find this ingredient in your local market. There isn't an adequate substitute, so if you don't find it, leave it out.

Mexican pink pine nuts. Their taste is sweeter than the standard white ones, and they leave no bitter aftertaste in your dish. If you can't find these pink pine nuts, it's better not to substitute the white ones.

Warm the oil in a large, heavy skillet and sauté the onion and garlic over medium heat until they turn a pale gold. Stir in the shredded meat and cook for five minutes. Add the cinnamon, pepper, and cloves, then, stir in the raisins and the two tablespoons of chopped walnuts. Add the chopped pear, apple, and finely diced biznaga cactus, and mix well. Add the tomatoes and salt to taste, and continue cooking over medium-high heat until most of the moisture has evaporated. Stir often so that the mixture doesn't stick. Let cool, cover, and set aside. The picadillo may be made and refrigerated a day or two in advance of final preparations.

Roasted chiles poblano, ready to peel, seed, and stuff. Photo courtesy Delicious Mexican Recipes.

Peel the chiles and make a slit down the side of each chile, just long enough to remove the seeds and veins. Keep the stem end intact. Drain the chiles, cut side down, on paper towels until completely dry. Cover and set aside. The chiles may be prepared a day in advance.

At least three hours in advance, put the walnuts in a small pan of boiling water. Remove from the heat and let them sit for five minutes. Drain the nuts and, when cool, rub off as much of the dark skin as possible. Chop the nuts into small pieces. Place the nuts, cream cheese, crema, and salt in a blender and purée thoroughly. Stir in the optional sugar, cinnamon, and sherry until thoroughly combined. Chill for several hours.

Preheat the oven to 250ºF. When ready to serve, reheat the meat filling and stuff the chiles until they are plump and just barely closed. Put the filled chiles, covered, to warm slightly in the oven. After they are thoroughly heated, place the chiles (cut side down) on a serving platter or on individual plates, cover with the chilled walnut sauce, and sprinkle with the chopped parsley and pomegranate seeds.

Chile en nogada as served at Restaurante Azul Histórico, Mexico City.

Chile en nogada as served at Restaurante Las Quince Letras, Centro Histórico, Oaxaca.

This dish may be served at room temperature, or it may be served slightly chilled. It is rarely if ever served hot.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.