Fishermen on Lake Pátzcuaro. Photo by Earl Leaf (1952), Michael Ochs Archives, courtesy Getty Images. Unless otherwise noted, all photos copyright Mexico Cooks!.

Mexico's state of Michoacán is a patchwork of cool pine-forested mountains bathed in freshwater streams and lakes, rocky surfers' paradises along the Pacific Ocean coast, and the Tierra Caliente, the hot, dry lowlands. The indigenous Purhépecha population, the largest of the four indigenous communities who live in this state, still retain many of their traditions and customs in today's 21st century life.

In the beginning, nothing existed. Everything was total darkness. Nothing was heard, nothing was seen, nothing moved. Everything was a great circle, without beginning and without end. Much time passed. Finally from the depth of the nothing and the darkness came a tiny ray of light. The small light ray grew until it formed a huge ball of fire which illuminated the darkness. From that great fire rose up Kurhikaueri, the giver of fire, who overcame the darkness with his enormous force of light. The father of the sun.

Their kingdom, centered in the town of Tzintzuntzan on the shores of Lake Pátzcuaro, is said to have been an advanced and prosperous civilization as early as 900 A.D.

Less is known anthropologically about the historical antecedents of the Purhépecha than about any other important Mexican group (the Olmecs, the Toltecs, and the Aztecs, for example). The Purhépecha had no written language and therefore kept no written record of their lives, culture, or activities. All of their history is extrapolated from post-first contact documents written by the Spanish. The Purhépecha language was established long before the arrival of the Spanish and is in no way related to any other indigenous language of Mexico–or to any other language in the world.

When the great collision occurred between the dark and the fire, four huge rays of light arose which were separated into four different points. Where each ray of light ended, four stars remained as permanent signs and four rays remained as the four paths which divided the newborn Universe.

In the early 1500s, the Lake Pátzcuaro basin had a population between 60,000 and 100,000 inhabitants spread among 91 separate settlements ranging over 25,000 square miles. Purhépecha government was strong, with effective social, economic, and administrative structure. A strong religion with many gods and goddesses underlay and supported the society.

Purhépecha woman selling flor de calabaza (squash flowers) from a wheelbarrow in Paracho, Michoacán.

What happened to the Purhépecha and their strong kingdom?

On February 23, 1521, the first Spanish soldier appeared on the borders of Michoacán. Even before this, however, the effects of the Spanish invasion had begun to be felt among the Purhépecha. The previous year, a slave infected with smallpox had come ashore after crossing the Atlantic Ocean with the army of Spaniard Pánfilo de Naravaez and had triggered a widespread and disastrous smallpox epidemic.

Tzuiangua, the Purhépecha calzonci (king) died in the smallpox epidemic of 1520. Measles and other diseases came along with the earliest Spaniards and led to further reductions in population. Partly as a result of these catastrophes, the young, newly-invested calzonci Tzintzicha Tangaxoana chose to accept Spanish sovereignty when the first Spanish soldiers arrived, rather than suffer the fate of Tenochtitlán, the grand Aztec pyramid city located near present-day Mexico City. As evidence of his submission, he accepted baptism and brought Franciscan missionaries into the region under his protection.

It is unclear whether the new young king did not fully understand the Spaniards' intentions and how their system worked, whether he thought he could pull the proverbial wool over their eyes, whether he was poorly advised, or some combination of the three.

The Spanish had intended to allow him to keep some symbolic measure of autonomy for himself and his empire as a reward for his cooperation. However, when the Spanish discovered that he was continuing to receive tribute from his subjects, they had him executed. On February 14, 1530, the last native king of the Purépecha was put to death at the hands of the conquerers.

So begins the mystical creation history of the Purhépecha people and Lake Pátzcuaro, the center of their spirituality. Still numerous and active in the modern world, the Purépecha maintain much of their supernatural culture in spite of the intrusion of globalization and the present-day world. The mid-20th Century, Mexican-Irish muralist Juan O'Gorman painted the history of the Purhépecha nation in the Pátzcuaro public library, still open on the Plaza Gertrudis Bocanegra (Pátzcuaro's small plaza). The mural depicts O'Gorman's vision of pre- and post-Spanish invasion Purhépecha life.

Just at this moment, Kurhikaueri began to work intensely with his light-filled hands. He molded a sphere from a ray of light, he hung it in space, and gave it the mission to illuminate the Universe. He named it Tata Jurhiata, the Lord Sun. Soon Kurhikaueri noticed that the light from the Lord Sun was monotonous and still, and Kurhikaueri thought of giving the Lord Sun a wife to help him light up the Universe. Thus he formed Nana Kutsi, the Lady Moon. Tata Jurhiata watched while Kurhikaueri molded Nana Kutsi, and she noticed him as well. In that way, love was born. Like all lovers, they dreamed of a way to meet one another. One time they met in the dominion of the moon and another in the dominion of the sun, and that is how the eclipses were produced. From their union, their daughter Kuerajperi was born.

This carved cantera (stone) statue of Bishop don Vasco de Quiroga stands at the side of the first hospital he founded in Michoacán, in Santa Fe de la Laguna, in 1533. Hospital, at that time, meant a center of hospitality, where weary travelers could rest and eat along their journey. The painted wall reads "Honor to Tata Vasco".

In 1533, don Vasco de Quiroga, a Spanish aristocrat, was installed as the first bishop of the province of Michoacán. At that time, the province was much larger than the present-day state. Don Vasco governed an area that encompassed over 27,000 square miles and 1.5 million people. Don Vasco oversaw the construction of three Spanish-style pueblos (towns), each of which included a hospital, as well as the great cathedral of Santa Ana in Morelia, numerous churches and schools, and founded the Colegio de San Nicolás Obispo (College of St. Nicholas the Bishop), the first school in all of the Americas. Quiroga is immensely important not only to the history of Michoacán but also specifically to the Purhépecha nation.

In The Christianization of the Purhépecha by Bernardino Verastique (pp. 92-109), the author states that the primary task assigned to Quiroga was to "rectify the disorder in which Niño de Guzmán had left the province after the assassination of the cazonci." Unlike Guzmán, who was a viciously murderous and enslaving conqueror, Quiroga was largely benevolent. He assumed a pastoral role of protector, spiritual father, judge, and confessional physician to the Purépecha.

He organized the Purhépecha villages into groups modeled on Thomas More's Utopia and extended his territorial jurisdiction, which brought him into direct conflict with the Spanish encomenderos (land grant holders). Quiroga recognized that Christianizing the Purépecha depended upon preserving their language and understanding their world view. He promulgated a multicultural, visual, and multilingual access to Christianity.

Even the Purépecha nation's name is debatable. Erroneously called Tarascans since the Spanish conquest, in the last 40 years the Purhépecha have begun to reclaim the actual name of their community. The term 'tarasco' means brother-in-law in the Purhépecha language. The newly arrived Spanish heard that term and misunderstood, mistakenly believing that it was the name of the entire nation.

Descendants of the Purhépecha remain in Michoacán, particularly in the Lake Pátzcuaro area. The language is still spoken, though only by a fraction of the population. A written Purhépecha language has been devised and is used in a regional newspaper, in books, and as signage.

Olive trees planted by the Spanish nearly 500 years ago still thrive in the churchyard at Tzintzuntzan, the former Purhépecha capital, on the shore of Lake Pátzcuaro. Some of the trees measure nearly 15 feet in diameter. In villages nearby, Purhépecha descendants still produce the crafts of the old days: wood carving, copper smithing, pottery making, textile production, and weaving tule (also known as chuspata, a lake reed) weaving. The present-day town has a population of less than one-tenth of the Purhépecha capital at the height of its power, and it continues to lose many of its young people as they migrate in search of jobs to other Mexican cities and to the United States.

Grinding Michoacán's native blue corn using the metate (grinding stone) and metlapil (its rolling pin). I took this photo just a few years ago.

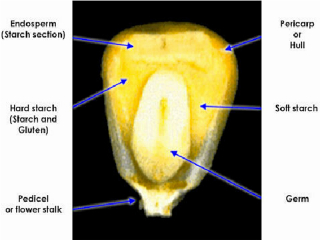

Anthropologists are of two minds concerning contemporary Purhépecha life. One group, the 'Hispanists', argues that the Purhépecha remnant has become primarily a Spanish-speaking Mexican peasant culture. Though they have maintained their language and some of their basic Mesoamerican cultural elements (in particular their diet of beans, squash, chiles, native corns, and other ingredients of their pre-first contact life), they have become Hispanicized with regard to their religious lives, their economy, and their forms of traditional or 'folk' knowledge. In contrast, the other group is more persuaded by the consistencies they see between traditional Mesoamerican culture and the modern-day life of the remaining Purhépecha. They note in particular the areas of relationship between language and culture, gender relations, socialization, and world view.

As time passed, Kuerajperi became a lovely young woman. Kurhikaueri, the giver of light, saw her and fell in love with her. He began to court her, and when he won her favor, he sent her four rays of light which remained on her forehead, on her womb, on her right hand and on her left hand. The lovely young woman was changed into Nana Kuerajperi, the mother of creation, who gave birth in a tremendous storm to all natural things: the Earth, the mountains, rivers, trees, flowers, and lakes. And that's how I was born, I was molded like a half moon with six beautiful islands. In this world, there is nothing more beautiful than I.

Today, more than 120,000 Purhépecha live in 16 municipalities in the Zona Lacustre (Lake Zone) and the Meseta Purépecha (Purépecha tableland) of Michoacán. Within those municipalites are numerous towns and villages. Most Purhépecha are bilingual. Generally the language spoken by the family at home is Purépecha. Children learn Spanish when they enter primary school. There are still approximately 10,000 Purhépecha who speak only their native language.

The present-day economy of the Purhépecha is based, for the most part, in agriculture. They grow native corn for their own use and grow wheat to sell. In the Zona Lacustre, a number of people still fish commercially.

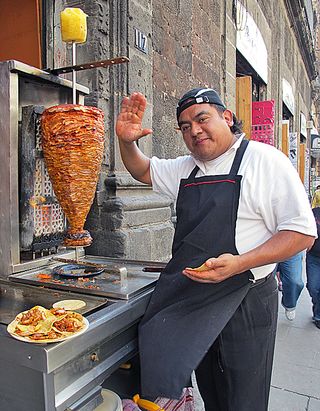

Another significant source of income is the creation of arts and crafts. In the mid-16th century, don Vasco de Quiroga taught the Purépecha not only Christianity but also the idea of self-sufficiency based on the refined production of items for daily use: pottery, textile weaving, copper smelting, mask making, and wood carving, among others. The making of utilitarian items was in place long before the Spanish arrived; Tata Vasco sent for artisans from Spain to work with the Purhépecha to improve the items that were already being made. Approximately 40,000 families in Michoacán presently work at one form or another of artesanía.

Moreover, I have been given peaceful and crystalline waters, so crystal-clear that they are like a mirror, and that's how I am used. You see, my grandmother, Nana Kutsi, combs her long silver hair every night when her rays are reflected in my waters. By day, my grandfather, Tata Jurhiata, reflects his golden rays in my waters, forming sparkles of every color. I am the lake of the ages. I am Lake Pátzcuaro.

The ancient Purhépecha believed that the Universe was divided into three parts: the region of the heavens, the region of the Earth, and the region of the dead. Each region had its own set of gods. The most important gods were those of the first region–the heavens–and among those the most important were Kuerajperi, the Lord of LIght, and Xaratongo, the goddess of the moon.

Many Purépecha continue to live in small villages, in some respects isolated from culture other than their own. Their ancient homes, called trojes, are made of heavy, hand-hewn thick pine boards. Each room of a troje is separate from every other room. The kitchen, living quarters, sleeping and storage rooms are individual small buildings. Family trojes are rapidly being sold as weekend cabins and for other non-Purhépecha use, and the Purhépecha are living in more modern dwellings.

Entrance to the Templo del Señor del Rescate, in Tzintzuntzan, former seat of the Purhépecha empire.

Today, the Purhépecha practice a Catholicism colored by their reinterpretation of the teachings of the early Franciscan and Dominican missionaries. Many Purhépecha believe that God, the Virgin Mary, Jesus, and the saints have special powers which interact among them. The devil, in some of his manifestations, has an importance which goes beyond that of the saints.

Life for the Purhépecha today is a battle for survival, both economic and cultural. Physical survival depends on many factors, including money sent home by the sons and daughters of the pueblos who now work in Morelia (the state capital), Mexico City, Guadalajara, and in the United States.

Cultural survival is constantly assaulted by the influences of television, technological advances (everyone has a cellular phone, everyone reads and posts to Facebook), everyone is connected via Whatsapp and Messenger), print advertising, and innovations brought home by the sons and daughters who work 'away'.

Social and political activism are crucial to the continuation of the Purhépecha nation.

Spiritual survival depends on the handing down of the old ways, the old traditions, by a generation of elders that is fast disappearing. The question of how and how much to mix with the mestizo community is not an idle one, but one which must be addressed if the Purhépecha are to survive as more than a curiosity in the modern world.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.