Night of the Dead (Noche de Muertos) grave decoration for a young man who died in a bicycle accident. The bicycle is life-size. Seen in the Panteón Municipal (town cemetery), Tzintzuntzan, Michoacán.

Several weeks ago Paco (a friend from Michoacán) and I were talking about differences in cultural attitudes among citizens of Canada, the United States, and Mexico. We ended by discussing the Noche de Muertos (Night of the Dead) customs here in Mexico.

Paco told me that before the Spanish conquerors, Mesoamerican natives considered death to just be a simple step toward a new life. Life was a circle: time before birth, time here on earth, time after death constituted a continuum with no end, like a golden ring on a finger. Communication between the spirit life of the living and the dead was an ordinary experience.

With the arrival of the Spanish and their Christian beliefs, the indigenous people were taught new ideas. Thoughts of death produced terror: in the final judgment, the just would receive their reward, and sinners would receive their punishment. The difficulty lay in not being counted among the sinners.

The original pre-Hispanic remembrance celebration of the dead took place during the Aztec calendar month dedicated to Mictecacihuatl, the goddess of the dead. That month of the Aztec calendar corresponds to present-day July and the beginning of August. Post-conquest Spanish priests moved the celebration to coincide with the eve of All Souls Day, which falls on November 2. It was a useless attempt to change what the Spaniards regarded as a profane New World festivity of mumbo-jumbo into a Christian solemn occasion. The modern day result is a festival characterized by a mix of pre-hispanic and Catholic rituals—a purely Mexican event.

In the late 1800's, José Guadalupe Posada popularized the notion of death partying through life.

Today in Mexico, death is played with, made fun of, and partied with. We throw our arms around it in a wickedly sardonic embrace and escape its return embrace with a side-step, a wink, and a joke.

Noche de Muertos (Night of the Dead) is celebrated during the chilly night of November 1, ending in the misty dawn hours of November 2. For Mexicans, the celebration represents something more than maudlin veneration of their dead relatives. The celebrations of Memorial Day in the United States or Remembrance Day in Canada are all too frequently devoted to a fleeting moment's thought of those who have gone before, with the rest of the day passed in picnicking and the anticipation of the soon-to-arrive summer holidays. In many parts of Mexico, the living spend the entire night in communion with the faithful departed, telling stories, swapping jokes, wiping away a tear or two.

Sugar hatchling chicks and funny spotted cows, ready for use on your ofrenda (altar) commemorating a deceased loved one.

The idea that death is found in the midst of life (and life in the midst of death) has given rise to different manifestations of extraordinary and original expressions of popular art in Mexico. Among those are the custom of making and decorating sugar skulls (often with the name of a friend or relative written across the forehead), pan de muertos (bread of the dead), drawings in which much fun is poked at death, and calaveras, verses in which living and dead personalities—usually celebrities in the arts, sciences and especially in politics—are skewered by their own most glaring traits and defects. We wait impatiently for the newspapers to give us the most hilarious of the annual poems.

Traditionally, ofrendas (personalized altars) are prepared in the home in honor of one or more deceased family members. The altar is prepared with the deceased person's favorite foods, photographs, and symbolic flowers. Traditions vary from community to community.

In Michoacán, the altar may be decorated with special breads and bananas. In Oaxaca, other foods and fruits are used. It's most common to decorate an altar with hot pink and deep purple papel picado (cut tissue paper) as well as with foods, flowers, and personal objects important to the deceased.

In many places, public ofrendas are set up in the town square, the local Casa de la Cultura, or in shops. Many public altars honor national heroes, personalities from the arts, and little-known friends or well-known public figures.

We use bottles of beer or tequila or another of the dead person's favorite drinks, a packet of cigarettes or a cigar, a prayer card featuring the deceased's name-saint and another of the apparition of the Virgin to whom the deceased was particularly devoted.

Foods on the altar can include a dish filled with mole poblano or other festive food that the deceased enjoyed in life, a pot of frijoles de la olla (freshly cooked beans), platters of tamales, pan dulce (sweet bread), and piles of newly harvested corn, pears, oranges, limes, and any other bounty from the family's fields or garden. The purpose of the offerings is not to flatter and honor to the dead, but rather to share the joy and power of the year's abundance with him or her.

Dolls made of cartón (cardboard) are usually sold at special markets specifically devoted to Day of the Dead items. The cempasúchil (gold flowers) and the flower known by several names: cordón del obispo or pata de león or even terciopelo (bishop's belt, lion's paw, or velveteen, the magenta flowers) adorn most graves and ofrendas (altars honoring the deceased).

In Michoacán, wild orchids are in season and blooming; these too are often used to decorate graves. Photo courtesy El Mural.

Approximately 75% of the literally millions of Mexican cempasúchil flowers used for Day of the Dead are grown in the state of Puebla.

The fresh flower most commonly used everywhere in Mexico to decorate both home altars and at the cemetery is the cempasúchil, a type of marigold. According to my friend Francisco, the cempasúchil represents reverence for the dead. Wild mountain orchids, in abundant bloom at this time of year and cut especially for the Noche de Muertos, signify reverence toward God. Dahlias, the floral symbol of Mexico, are also used profusely on both home altars and in cemeteries. In addition, huge standing coronas (wreaths) of colorful ribbons and artificial flowers adorned with lithographs of saints, various manifestations of the Virgin Mary, or Jesus are used more and more frequently in Mexican cemeteries.

Because the social atmosphere of this celebration is so warm and so colorful—and due to the abundance of food, drink, and good company—the commemoration of Noche de Muertos is much loved by the majority of those who observe it. In spite of the openly fatalistic attitude exhibited by all participants, the celebration is filled with life and is a social ritual of the highest importance. Recognition of the cycle of life and death reminds everyone of his or her mortality.

Catrines, in this case clay figures of well-dressed skeletons, represent the vanity of life and the inescapable reality of death.

On the day of November 1 (and frequently for several days before) families all over Mexico go to the cemetery to clean and decorate the graves of their loved ones. With machetes, brooms, shears, hoes, buckets, metal scrapers and paint, the living set to work to do what needs to be done to leave the grave site spotless.

Is the iron fence around the plot rusty? Scrape it and paint it till it looks brand new. Are there overgrown weeds or bushes? Chop them out, cut them back. Have dead leaves and grass collected at the headstone? Now is the time to sweep them all out. There is usually much lamenting that the grave site has been allowed to deteriorate so much throughout the year—this year we won't let that happen again, will we?

Sugar skulls are a Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) tradition in Mexico. Buy one and have the name of your friend written on the forehead with stiff sugary icing. Your friend will be delighted with the gift.

In many places, November 1 is celebrated as the Day of los Inocentes or Angelitos (the Innocents, or Little Angels)—the little children who have died. In Michoacán on the Day of the Little Angels, the baptismal godparents are responsible for bringing a wooden frame for the flowers, for bringing the cempasúchil and the wild orchids. The godparents bring sugar angels or animals similar to the sugar skulls. They may also bring new clothing for the dead child, and a new toy or two. At the parents' home, preparation of food and drink is underway so that family and friends may be served. Cohetes (booming sky rockets) announce that the procession, singing and praying, is proceeding to the cemetery.

In the late evening of November 1, girls and women arrive at the graves of adults with baskets and bundles and huge clay casseroles filled with the favorite foods of the deceased. A bottle or two of brandy or tequila shows up under someone's arm. Someone else brings a radio and wires it up to play.

Watch a bit of the tradition: Day of the Dead in Mexico

A tiny sugar skeleton band, made in Michoacán for the Noche de Muertos.

In another part of the cemetery, a band appears to help make the moments spent in the cemetery more joyful and to play the dead relatives' favorite songs. Sometimes families and friends adjourn to a nearby home to continue the party. There's even a celebrated dicho (saying) that addresses the need for this fiesta: "El muerto al cajón y el vivo al fiestón." (The dead to the coffin and the living to the big blowout.")

The shimmering lake is made of flower petals!

Although the traditional observance of Noche de Muertos calls for a banquet either at the cemetery or at home during the pre-dawn hours of November 2, families in the large urban areas of Mexico City, Monterrey, Guadalajara, and others, families may simply observe the Day of the Dead rather than spend the night in a cemetery.

Their observance is frequently limited to a special family dinner which includes pan de muertos (bread of the dead). In some areas of the country, it's considered good luck to be the person who bites down on the toy plastic skeleton hidden by the bakery in each round loaf.

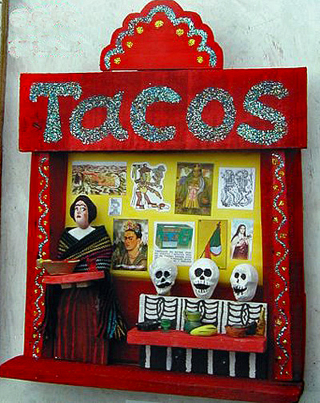

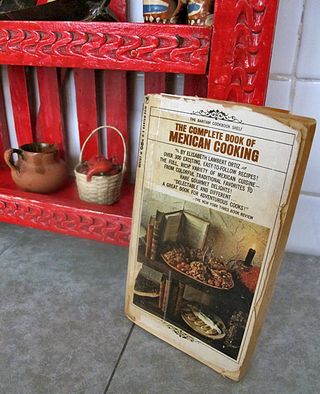

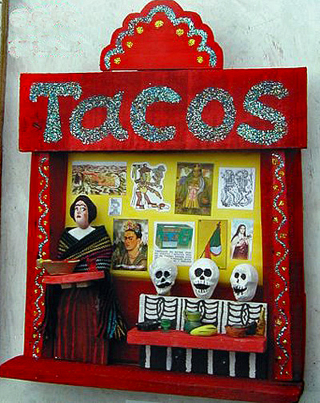

A small nicho (shadow box) by artisan Miguel Paredes, representing a Day of the Dead taco stand. An excellent place to buy this kind of nicho is Bazar Sábado in the San Ángel neighborhood of Mexico City. The outdoor and indoor market there is open every Saturday, and these little boxes are available year 'round.

Friends and members of the family give one another little gifts which can include tiny clay skeletons dressed in clothing or set in scenes which represent the occupations or personality characteristics of the receiver. The gift that's most appreciated is a calavera (sugar skull), decorated with sugar flowers, sparkling sequins, and the name of the recipient written in frosting across the cranium.

The pre-Hispanic concept of death as an energy link, as a germ of life, may very well explain how the skull came to be a symbol of death. That symbol has been recreated and assimilated in all aspects of Mexican life. The word calavera can also refer to a person whose existence is dedicated to pleasure—someone who does not take life seriously. The mocking poems of this season, the caricatures drawn with piercingly funny accuracy, the sugar skulls joyfully eaten by the person whose name they carry: all of these are an echo of pre-Hispanic thought, inherited by present-day Mexico.

From Guanajato: skeletal figures made of cartón (cardboard).

This tradition which recognizes that death is a part of the circle of life brings ease and rest to the living. Hearts heal, souls reaffirm their connections. Though beyond our view, the dead are never beyond our memories. Every November 1, the dead come home, if only for the night.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.