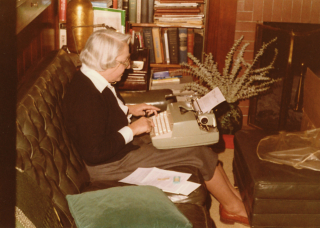

Mexico Cooks!' mother, circa 1980. She tried her best to give me good advice, but I was often loathe to listen.

In November 1969, she suggested that the March on Washington, against the war in Vietnam, might be overcrowded. I went anyway, and it was packed–but the experience was entirely worth being smooshed like a sardine in a can.

Over the course of several years, she warned me about wanting to do battle with the New Year's Eve crowds in New York City's Times Square. Although the idea of squeezing in still piques my interest, I haven't been there yet.

My mother didn't know about Mexico City's wholesale fish market, La Nueva Viga, but had she known, she would have insisted that Viernes Santo (Good Friday) was not the day to go. This photo, taken on Good Friday 2017, barely does justice to the incredibly jammed aisles at La Nueva Viga, Latin America's largest fish market and the second largest fish market in the world. Only the Tsukiji fish market in Tokyo, Japan, surpasses the volume of fish and seafood sold annually at La Nueva Viga. The Tsukiji market averages 660,000 tons of fish and seafood in yearly sales; La Nueva Viga racks up around 550,000 tons. I think 549,000 tons must sell just on Good Friday, the last day of abstinence from meat during Lent.

The main entrance at La Nueva Viga is on Prolongación Eje 6 Sur, Colonia San José Aculco, Iztapalapa. The facility extends over nearly 23 acres (9.2 hectares), with 202 wholesale warehouses, 55 retail warehouses and 165 sellers in total. On any given ordinary day, the market receives between 20,000 to 25,000 customers, mostly restaurant owners in Mexico City and the areas immediately around it. On Good Friday, the clientele is mainly retail: home cooks looking for bargain fish and seafood for the Friday before Easter. Both fish and good prices abound and it seems like half the city is there to buy–what a challenge!

On Good Friday 2017, friends Rondi Frankel, Magdalena Mosig, and I made the trek to La Viga. Rondi drove and Magdalena acted as our guide; she at one time owned a restaurant and always bought fish and seafood at the market. It was a great treat–not to mention an enormous help!–to have her show us the ropes. From my street, south of Mexico City's Centro Histórico, the trip to La Viga took about 45 minutes. Because it was Good Friday, there was no traffic at all until we were close to the market–and then–yikes! Bumper to bumper, several lanes of near-parking lot, hundreds of street vendors of everything from cold bottled water to kites, partial sleeves (wrist to above the elbow) to wear while driving so your arm doesn't get sunburned, thin, crisp, sweet fried morelianas (a kind of cookie), chewing gum, single cigarettes, bags of ready-to-eat mango with chile, limón, and salt, soft drinks, straw hats–anything at all that a person might want.

The massive parking lots for La Viga were completely filled, so we drove a couple of blocks past the fish market and found a private lot. Once we were finally at the market, we sloshed through salty puddles, thousands of fish scales flying through the air, and the clang of huge knives hitting long fish-cleaning tables. Then up a few stairs and we were smack in the middle of the jostling, shoving crowds, pushing between rows of vendor stalls.

Extra-jumbo shrimp! That's Rondi's normal-size adult hand, for comparison. Each shrimp measured approximately 8" long with the head on. The price? $280 pesos (approximately $15 USD) per kilo–or $8.00 USD per pound. If I had to guess, I'd say these huge shrimp are about 5 or 6 to the pound.

Beautiful, fresh, and enormous huachinango (red snapper) were everywhere. These measured about two feet long–great big ones!–and looked fresh as the morning. According to the sign, they were caught in the waters off the state of Veracruz, on the southeastern Gulf coast of Mexico. The darker fish to the left are mojarra (sea bream), delicious but very bony.

Another vendor displayed his mojarra with the gill flap raised. It's easy to see by the condition of the gill that the fish is wonderfully fresh. This is exactly how a gill

should look when you're buying: firm and pink.

Many vendors had huachinango for sale; these were offered at a booth farther down the aisle from the first photo of huachinango. You can tell by the condition of the eye that this lovely fish was freshly caught. The eye is shiny, not sunken into the head, and full of light. My only hesitation in buying a fish was the length of time that I would be carrying it around in a bag prior to getting it home and into the refrigerator: too long in the very warm Mexico City springtime weather.

The smallest of these almeja gallo (rooster clams, at the rear) carried a sign reading, "For soup". Their price was $20 pesos (about $1.40 USD) per kilo. As the sizes increased, the prices increased. The most expensive were the ones on the right, at 35 pesos the kilo.

Look at this incredible tower of live blue crabs, tied up with reeds! Mexico Cooks! has always seen blue crabs in retail markets, always quite moribund, so it was wonderful to discover that they actually arrive at La Viga still living.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j-bSv1XADag&w=420&h=315]

Proof positive! Watch these babies wiggle! The first thing that crossed my mind to prepare was a big platter of Chinese blue crabs in black bean sauce.

Fresh red octopus, piled high. $245 pesos the kilo.

These are langostinos–where you live, they may be known as crayfish (although they are a completely different species).

Oysters: piled-up huge costales (in this case, open-weave polypropylene sacks) of oysters. Oysters are sold by the costal, or shucked in their liquid in plastic bags as long as your arm, and also in smaller containers for home consumption. Some oysters come from the southeastern Mexican states of Tabasco and Campeche; others come from the Pacific Coast states of Baja California and Sinaloa. Mexico is the fourth-largest producer of oysters in Latin America. These particular oysters were for sale at $150 pesos the sack. "Isn't that about $8.00 USD?" Why yes, it is.

Oysters, ready to eat. Served with fresh Mexican-grown limones (Key limes), a dozen cost 100 pesos at this sit-down restaurant in La Viga.

What would Mexican seafood be without a bottled table salsa to season it–along with limón and maybe a wee pinch of salt? What we see here is a small selection of the hundreds of salsas from which to choose.

And truly, it wouldn't be right to serve seafood without a splash of home-made salsa bruja: witches' sauce! I keep mine on my counter and top it off with more vinegar as needed. The salsa is a mixture of vinegar with onion, garlic, carrot strips, bay leaf, rosemary, chile (I use serrano), oregano, a couple of cloves, salt, and pepper. Stuff all the vegetables and herbs into an empty wine bottle, fill with vinegar, cork, and allow to sit for several days. Voilà, salsa bruja!

The next time I go to La Nueva Viga, I will abide by what my mother surely would have advised: go on a day when half of Mexico City isn't there! You come, too–we'll have a marvelous time!

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.