Pan de muerto! This seasonal bread starts making an appearance in Mexico bakeries as early as the end of August, but the majority is made and sold between mid-October and the first week of November, just in time for one to enjoy for breakfast (with a cup of hot chocolate, or an atole, or an herbal tea–or for supper (with a cup of ditto that list), or just because you want one and you want it now! At the end of the article, I've added a photo of my all-time favorite pan de muerto, produced here in Morelia, Michoacán, where I have been living for the last several years.

Pan de muerto (a special bread for Day of the Dead), almost ready for the oven at Panadería Maque, Calle Ozululama 4, at the corner of Calle Citlatépetl, Colonia La Condesa.

Late in October, a bread baker I know suggested that in honor of Mexico's Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead), we go poking around in bakeries. Pan de muerto is one of the traditional treats set out on altars to entice the spirits of the dead back for a visit with the living, and every bakery has its own recipe. As it happened, neither of us had a lot of time on the appointed day, so we made a list of eight spots to visit in Colonia La Condesa. We set off on foot with high hopes of finding sublime breads.

The family-size pan de muerto at Panadería Maque, wrapped in cellophane and ready to go home with you. We calculated that it would serve eight or more people, with a good-sized slice or more for each person. A few years ago, this size cost just under 400 pesos.

Our first stop–we arranged our bakeries in a big oval starting with the one closest to Mexico Cooks!' home and ending as near as possible to the same spot–was at Panadería Maque. Maque is a several-bakery/coffee shop chain open from 8AM breakfast to 10PM, when it serves a light supper. We were impressed by the big crowd at the outdoor and indoor tables, the long line waiting to be seated, and the bustling wait staff whizzing by with coffee, great-looking sandwiches, and lots of pan de muerto. We took some photos and made a note to return for breakfast another morning when we both had more time.

Not on our list but in our path, at the corner of Calle Ozululama and Av. Amsterdam: Louis Robledo's Tout Chocolat, where the pan de muerto was made with chocolate. Jane bought one hot out of the oven to take home. She also bought each of us a delicious macarrón. They were very nearly as good as the ones I tried last spring in Paris.

Next on our list was Panadería La Artesa, at Alfonso Reyes 203, corner Calle Saltillo. Mexico Cooks! often stops at La Artesa for baguettes and pan de agua, both of which are good but not spectacularly so. The owner noticed that both my companion and I had cameras with us; he started berating us loudly with, "No photos! No photos! Put the cameras away!" We opted to leave without an interview and obviously without photos.

As we strolled along, we noticed this sign: MANDUCA. Recently opened at Calle Nuevo León 125-B, this terrific bakery was also not on our list–but what a find! Trendy but not precious, all its bread is baked on the premises.

Real bread! Manduca's delightful manager, Alejandra Miranda Medina, told us that the baker is German.

We couldn't leave; hunger suddenly overcame our need to step lively. My friend ordered a pan de muerto and coffee; I asked for one of the pretzel bread individual loaves and butter. The pretzel bread was marvelous, the heavily anise-flavored pan de muerto a little less so. The outside seating (there are also tables inside) was comfortable and pleasant.

Manduca's pan de muerto enticed us to stay, but each of us prefers this bread with more orange flavor and a lighter touch of anise.

We continued to meander down Calle Nuevo León, looking for Panadería La Victoria, our next destination.

La Victoria, at Calle Nuevo León 50 (almost at the corner of Calle Laredo), bills its style as Rioplatense (from the River Plate area that lies between Argentina and Uruguay) rotisserie and bakery. The chef is from Uruguay. These little sweet breads, called vigilantes (watchmen), are filled with a sweetened creamy cheese and topped with ate de membrillo (sweet quince paste). In Uruguay, these are said to be the favorite sweet bread of policemen–hence vigilantes.

Pan de muerto available at La Victoria. These mini-breads (compare them with the ordinary size of the tongs at the right of the photo) are just the right size for two or three bites.

We spent a few minutes looking for Panadería Hackl (Calle Atlixco 100, between Calles Campeche and Michoacán, but realized distance and our rapidly disappearing time meant that we would have to come back another day.

We walked through Fresco by Diego (Fernando Montes de Oca 23, near the corner of Calle Tamaulipas), which offers some breads but is primarily a restaurant.

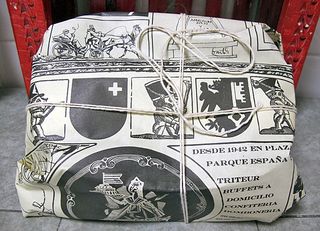

Our last stop was Pastelería Suiza, at Parque España 7 (between Calles Oaxaca and Sonora). It's a 70-year-old Mexico City institution with several sucursales (branches); this location is the original. Mention this bakery to almost anyone in the city who loves pan dulce (sweet bread) in and the response will be a sigh of blissful longing.

On November 2, the only bread for sale at Pastelería Suiza was pan de muerto, and the only pan de muerto left, in several sizes, was split horizontally and stuffed with a huge schmear of nata (thick sweet cream). It looked like the Holy Grail of pan de muerto. I could not resist buying two individual-size panes de muerto to take home.

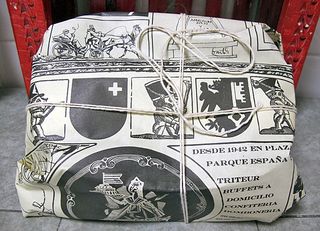

You choose your bread, take it to the wrapping station, pick up your ticket, pay at the cashier, and then go back for your bread. The wrapping staff put the pan on a tray, then surrounded it with a cardboard collar.

Wrapped up in paper and string, the package has a come-hither look equal to the bread itself.

We could hardly wait–the Pastelería Suiza pan de muerto and a cup of hot tea would be our cena (supper) that night.

The verdict? The thick mound of nata was quite honestly an overkill of creamy sweetness. And the bread itself? The texture was wrong, more like a dry, crumbly, unpleasant muffin than like traditional pan de muerto. The bread had no flavor–not a drop of orange, not a drop of anise, nothing. It was a tremendous disappointment. Big sigh…but not blissful in the least.

So, you might ask: you walked all over Colonia La Condesa, you sniffed breads, you tasted breads, and nothing really satisfied Your Pickiness. What now?

A few days prior to Mexico's Día de los Muertos, another companion and I stopped at what is essentially a corner bakery, located at the corner of Av. Insurgentes and Av. Baja California, hard by the Metro station a couple of blocks from my apartment. Panificadora La Espiga (the Spike of Wheat breadmaker) is large but ordinary, with not much to recommend it other than its proximity to the house. A seasonal craving for pan de muerto had us by the innards, though, and we bought two small ones. They looked generic, with the traditional sprinkle of sugar: no nata, no chocolate, nothing special at all.

Pan de muerto, La Espiga.

When I tasted the pan de muerto, I was surprised. My exclamation was, "A poco!" (Are you kidding me? I don't believe it!) The texture was dense, slightly layered, and moist. The not-too-sweet flavor leaned toward the orange, with just a hint of anise. Who could have guessed! It was perfect. My friend and I had wandered far afield, spent time and money in all those uppity Condesa bakeries, and even before our pan de muerto crawl, I had already tried the best bread of the bunch.

Now for the 2021 update, direct to you from Morelia, Michoacán! A week or so ago, we went to visit our wonderful friend Beto at Beto Chef Michoacano–and lo and behold, he and Lalo had at least two trays of pan de muerto, just about ready to take out of his wood-fired beehive oven. We sat down to wait for a minute and he set a plate of two hot-from-the-oven chocolate conchas (a sweet bread crowned with a sweet chocolate topping) in front of us–just to keep us happy until the pan de muerto finished baking. We split one, eating two would have been truly sinful. The concha was excellent, the crown made from chocolate de metate (local stone-ground chocolate) and the bread itself outstanding. And then…and then…pan de muerto, hot from the oven, to take home! We were too full from the concha to eat the pan de muertos right then and there, but we ate one for breakfast the next morning and I am here to tell you, it was PERFECT. The flavor was just the right delectable combination of orange and anise and yeast, the bread was just the right texture and consistency. There's a saying in Mexico: como Dios manda–it means "the way God intends–and this was 100% IT for pan de muerto. If you're in or near Morelia, head on over to see Beto and buy pan de muerto for you and your family and friends. Beto charges $15 pesos for one of the panes in the photo below; that's about the US dollar equivalent of 75 cents apiece. Buy a dozen, buy two dozen! Give some to your pals! Freeze some! And please give Beto a hug from Mexico Cooks!.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.