Tamales Oaxaca style, wrapped in banana leaves. These tamales, prepared in the kitchen at Restaurante Las 15 Letras in Oaxaca, were filled with armadillo meat. They were absolutely delicious.

When I was a child, my mother would sometimes buy a glass jar (I have conveniently forgotten the brand name) packed with what we called "hot tamales". Wrapped individually in parchment paper, covered in a thin, brackish, tomato-y fluid, these slippery travesties were all I knew of tamales until I moved to Mexico.

The first Christmas season I that I lived in this country, over 40 years ago, my neighbor from across the street came to my door to deliver a dozen of her finest home-made tamales, fresh from the tamalera (tamales steamer). I knew enough of Mexico's politeness to understand that to refuse them would be an irreparable insult, but I also was guilty of what I now know as contempt prior to investigation. I did not want tamales. The memory of those childhood tamales was disgusting. I smiled and thanked her as graciously as I could.

"Pruébalos ya!" she prodded. "Taste them now!" With some hesitation I reached for a plate from the shelf, a fork from the drawer (delay, delay) and unwrapped the steaming corn husk wrapper from a plump tamal she said was filled with pork meat and red chile. One bite and I was an instant convert. My delighted grin told her everything she wanted to know. She went home satisfied, wiping her hands on her apron. I downed two more tamales as soon as she was out of sight. More than 40 years later, I haven't stopped loving them.

A three-compartment tamalera: bottom left, Oaxaca-style tamales wrapped in banana leaves. Right, central Mexico-style tamales, wrapped in corn husks.

[youtube=://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QUWjZTAWMQU&w=350&h=315]

The 'official' voice of the ubiquitous Mexico City tamales oaxaqueños vendors. One of these carts visits our street every night at about ten o'clock.

Christmas in Mexico is a time for special festive foods. More tamales than any other food come from our Christmas kitchen. Tamales of pork, beef or chicken with spicy red chile or semi-tart green chile, tamales of rajas con queso (strips of roasted poblano chiles with cheese), and sweet pineapple ones, each with a single raisin pressed into the masa (dough), pour in a steady, steaming torrent from kitchen after kitchen.

I asked my next door neighbor what she's making for Christmas Eve dinner. "Pues, tamales,que más," she answered. "Well, tamales, what else!"

I asked the woman who cleans my house. "Pues, tamales, que más!"

I asked the woman who cuts my hair. "Pues, tamales, que más!"

And my handyman. "What's your wife making to eat for Christmas Eve, Felipe?"

I bet by now you know what he replied. "Pues,tamales, que más?"

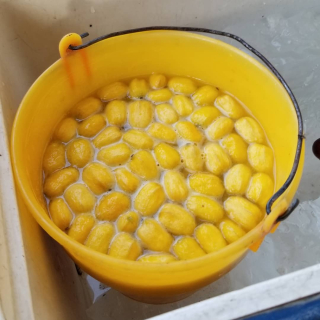

Obviously there are other things eaten on Christmas Eve in Mexico. Some folks feast on bacalao a la vizcaína (dried salt codfish stewed with tomatoes, capers, olives, and potatoes). Some women proudly carry huge cazuelas (rustic clay casserole dishes) of mole poblano con guajolote (turkey in a complex, rich sauce of chiles, multiple toasted spices, and a little chocolate de metate (stone ground chocolate), thickened with ground tortillas) to their festive table. Some brew enormous ollas (pots) of menudo (tripe and cow's foot soup) or pozole (a hearty soup of nixtamaliz-ed cacahuatzintle, a native white corn, chiles, pork meat, and condiments) for their special Christmas Eve meal, traditionally served late on Nochebuena (Christmas Eve), after the Misa de Gallo (Midnight Mass).

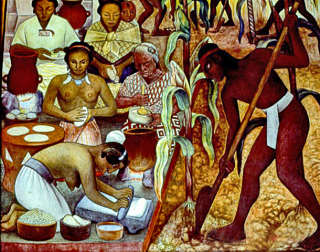

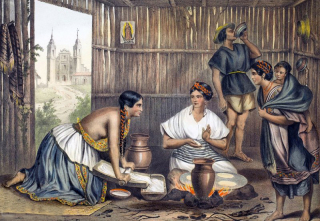

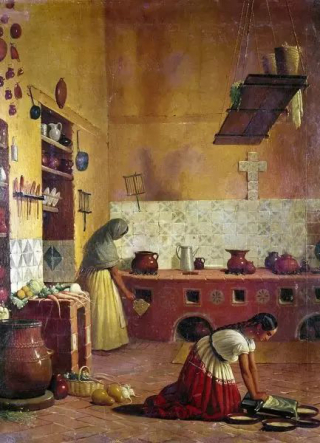

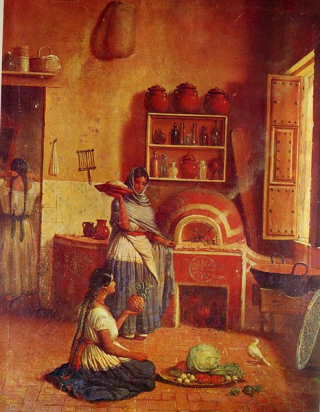

As an exceptional treat, we're sharing part of a photo essay by my good friend Rolly Brook, may he rest in peace. The photo essay is all about tamales, their ingredients and preparation. Rolly's friend doña Martha cooks a whole pig head for her tamales; many cooks prefer to use maciza—the solid meat from the leg. Either way, the end result is a marvelous Christmas treat.

Doña Martha Prepares Tamales for Christmas

Doña Martha, now with Rolly in heaven, begins to take the meat off the cooked pig head.

Doña Martha mixes the shredded meat from the pig head into the pot of chile colorado (red chile sauce that she prepared earlier in the day).

Doña Martha needs a strong arm to beat freshly rendered lard into the prepared corn for the masa. The lard and ground corn must be beaten together until the mixture is as fluffy as possible.

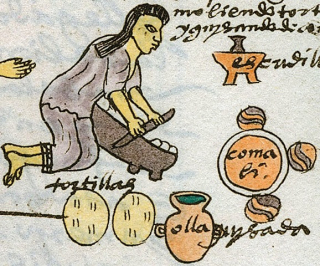

Doña Martha's daughter spreads masa (corn dough) on the prepared hojas de maíz (corn husks).

Corn husks spread with masa, ready to be filled.

Doña Martha fills each masa-spread corn husk with meat and chile colorado.

Folding the hojas de maíz is an assembly-line process involving the whole family.

Tamales in the tamalera, ready to be steamed. Steaming takes an hour or so.

One small plateful of the finished tamales!

The photos only show part of the process of making tamales. You can access Rolly's entire photo essay on his website. A few years prior to his death, Rolly graciously allowed Mexico Cooks! the use of his wonderful pictures. Although Rolly is now having his Christmas tamales in heaven, his website is permanently on line for the benefit of anyone who needs almost any information about life in Mexico.

Can we finish all these tamales at one sitting? My friends and neighbors prepare hundreds of them with leftovers in mind. Here's how to reheat tamales so they're even better than when they first came out of the steamer.

Recalentados (Reheated Tamales)

Over a medium flame, pre-heat an ungreased clay or cast iron comal (griddle) or in a preheated heavy skillet. Put the tamales to reheat in a single layer, still in their corn husk wrappers. Let them toast, turning them over and over until the corn husks are dark golden brown, nearly black. Just when you think they're going to burn, take them off the heat and peel the husks away. The tamales will be slightly golden, a little crunchy on the edges, and absolutely out of this world delicious.

Provecho! (Good eating!)

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here to see new information: Tours