Pouring miel de piloncillo (spiced raw brown sugar syrup) over the second layer of capirotada. The cazuela (clay dish) measures about 14" in diameter at the top.

Capirotada is the iconic Mexican dessert during Lent. It has its origins as long ago as the fourth century, in Rome. The history of the Roman dish is similar, but the dish itself is completely different from the capirotada we know in Mexico today. The list of Roman ingredients included bread soaked in vinegar and water, layers of chicken livers, capers, cucumber, and cheese. Only two of the ingredients that the Romans used 1600 years ago are the same as the ones we use today: slices of bread, and cheese–and even the cheese is optional today.

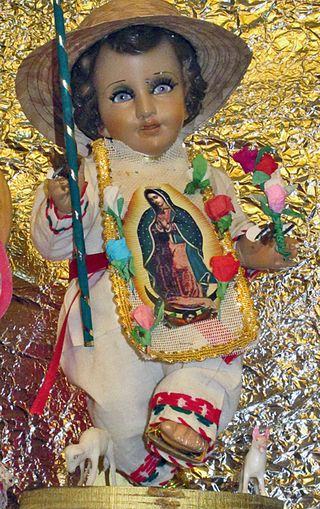

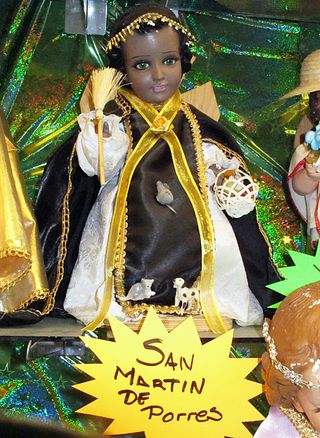

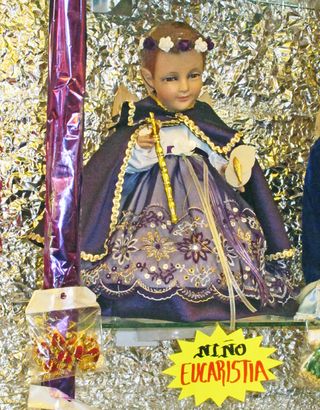

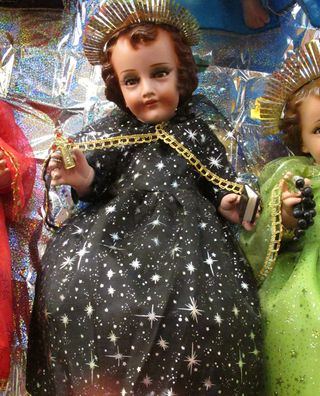

The cofradía Siervo de la Nación (association members of the Nation's Servant) makes the silent, many blocks long pilgrimage over Morelia's main street on Viernes Santo (Good Friday). The groups of the cofradías all walk in similar costume; each cloak may be a different color, but their sole purpose is to give anonymity to each individual in the group as they walk the length of this profoundly spiritual and humble procession.

Even the name capirotada has an unusual origin. It's derived from the word "capirote", the tall pointed hat that is part of the cloak used by the cofradías (religious individuals who form a church-associated group with pious ends) as they walk the Procesión del Silencio on Good Friday evening. The Procesión del Silencio takes place in cities and towns all over Mexico and in Spain.

The primary ingredients for capirotada. Clockwise from nine o'clock: toasted peanuts, 2 large cones of piloncillo, Mexican stick cinnamon, raisins, fresh orange peel, whole allspice, anise seeds, cloves–and in the center, finely diced acitrón.

Here's the queso fresco I bought for the capirotada. It's a milder flavor than the queso Cotija. This small cheese weighed about 120 grams and was just the right amount to crumble over the layers of bread.

The recipe came with the Spanish to Nueva España (what is today's Mexico) and has changed over the course of 500 years until it has become the dessert that we know today. Since long ago, the recipe contains:

–densely textured white bread, thoroughly dried and hard.

–optional stale tortillas to line the bottom of the cazuela or other dish you use

–freshly rendered pork lard

–vegetable oil

–cones of piloncillo (Mexican raw brown sugar)

–fresh orange peel

–fragrant cloves

–Mexican cinnamon stick

–allspice

–anise seeds

–shelled and skinned peanuts, toasted

–filleted almonds, toasted (optional)

—acitrón, a kind of crystallized cactus (optional)

–about a teaspoon of sea salt or table salt

–raisins

—queso Cotija or queso fresco (Cotija or fresh farmer's cheese (optional)

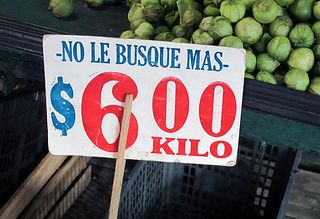

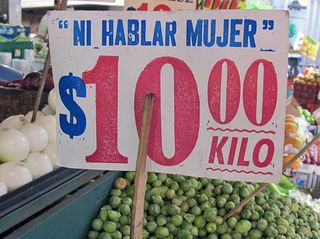

I purchased this already dried and buttered bread, ready for making capirotada, in a market in Michoacán, where I live. Numerous vendors offer the slices by the kilo (2.2 pounds) or by the bag. I bought a bag of about 10 very wide slices, which I sawed in half with a serrated knife so that I could fit them into a medium-size clay cazuela.

The recipe is simplicity itself. If you are using fresh bread, you'll need to slice it into 1/2" slices and let it dry for up to four nights, turning it every little while, until it is very hard on both sides. Then you smear both sides of the dried slices with butter and fry the slices in a liberal amount of freshly rendered pork lard mixed with vegetable oil. In many cities and towns of Mexico, one can buy pre-sliced, pre-buttered, pre-fried bread to use for capirotada. I did, its photo is just above.

Canela (Mexican cinnamon) sticks can be as much as a yard long. They're much softer and flakier and flavorful than the sort of short, hard, unbreakable cinnamon sticks sold packaged in most of the United States. One can buy Mexican cinnamon sticks at a Latin grocery store; look for one near your home. In the photo, you see raisins to the right of the cinnamon.

Here's a steamy shot of the miel de piloncillo as it simmers in a stainless steel pot. You can see the orange peel, the raisins, and the cinnamon stick.

I used two of the large cones of piloncillo (on the left). With this amount of piloncillo, the sweetness of the syrup was perfect. Piloncillo is available in a Mexican market near your home–and you might even find it packaged in your favorite supermarket, in the Mexican canned and dried food aisle.

Once the bread is prepared, make the miel de piloncillo. I used two large cones of piloncillo and a liter of water to start the process. Put the piloncillo, the water, about 10-12 inches (broken into two pieces) of a Mexican cinnamon stick, 2 or 3 fragrant cloves, the fresh orange peel, about 1.5 teaspoons of anise seed, and 2 or 3 whole allspice into a medium-size pot. Bring the pot to a boil and then lower the heat until the water is just simmering. Allow it to simmer until the piloncillo is completely dissolved; this might take as much as 10 minutes. You can allow the syrup to reduce just a little bit; you'll need the full amount of thin syrup to pour onto the layers of the capirotada. Turn off the fire and set the pot aside.

Next, liberally grease your cazuela or baking dish with freshly rendered pork lard. You can see in the photo that 'liberal' is what you want: don't stint. Smear the lard, on the bottom of the dish and right up the sides! Pork lard adds flavor to the capirotada that you can't get with any other fat. TIP: the lard you want is available by weight at a Mexican market and maybe at your supermarket. But DO NOT buy that cold brick of white hydrolyzed lard that's sold in your supermarket's meat or dairy case. It has no flavor and excuse me, is basically disgusting.

Now you will put a single layer of bread into the cazuela and top it with the amount of peanuts, raisins, acitrón and crumbled cheese that you like. I used about 50-60 grams of each per layer–maybe a few more peanuts. Once the first layer was assembled, I poured about a cup of the miel de piloncillo over it, soaking it well. The quantity of bread I bought made three layers; three fit very nicely into my cazuela. On each layer of bread, I scattered approximately the same amount of the ingredients I'd put on the first layer, and poured about the same amount of miel de piloncillo over each successive layer. The kitchen smelled fantastic!

The finished product! Once the capirotada was completely assembled, I put it into a pre-heated 180ºC (350ºF) oven for about 10-15 minutes. The oven is optional; your capirotada will be just as delicious if you don't bake it at all.

Not only is capirotada a traditional Lenten dessert, it also has a strongly spiritual essence. The Spanish are said to have used it as a teaching tool to give the indigenous population of Nueva España an understanding of the death and resurrection of Christ.

–the bread alludes to the Body of Christ

–the miel de piloncillo represents His blood

–the cinnamon stick looks like the wood of the cross where He was crucified

–the clavos (cloves) have the same shape and the same Spanish-language name as the nails in His hands

–the white cheese reminds us of the sheet that remained in the tomb when He arose from the dead

Although capirotada is richly delicious, and its history is also rich, today's reality is that home-made capirotada is not prepared as often as it was in years gone by. Yes, you can buy it already prepared in many towns in Mexico, and it's important to support the women who prepare it. Nevertheless, little by little the tradition is being lost. It's important that each of us do her/his part to make and eat something this significant and delicious–and with a five hundred year history on our Lenten tables. When one prepares it, it brings back so many memories of our childhood, our families, and our friends. It preserves the long tradition. Truly, it's well worth the time to prepare this simple recipe. During this Lenten season, let's commit ourselves to making capirotada and sharing it with those dearest to us.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.