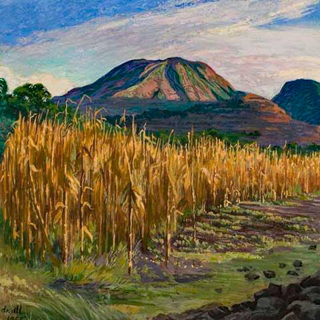

Did you know that vanilla–that leathery, wrinkled, don't-know-what-to-do-with-it, dark-brown bean in the back of your pantry, that bottle of extract in your cupboard, the ice cream that drips from your cone–is the pod of an orchid that originally grew only in Mexico? Since long prior to Spain's arrival in what we know today as Mexico, Vanilla planifolia (flat-leafed vanilla) grew in the cool forests of the low easternmost mountains near the Gulf of Mexico–specifically, in and around Papantla, Veracruz. Today, the area produces about 80% of the vanilla grown in Mexico. The orchids were not in bloom while we were there; hence this photo, courtesy Wikipedia.com.

In our search for Veracruz vanilla, we stopped here: Vainilla Gaya, one of the original Italian vanilla growers in Mexico. I had made an appointment for a tour, but we arrived late after erroneously going to another of Gaya's locations. Nevertheless, we were well-attended and able to see–albeit quickly–the areas of 'beneficio' (betterment), where green vanilla pods, newly harvested from vines in commercial production rooms, are cured and fermented both in ovens and in the open air.

One of the growing rooms at Vainilla Gaya. Vanilla is a vine that requires the support of jungle trees, of individual limbs, or, in this case, of metal and bamboo supports. Click on any photo to enlarge it.

Trays of vanilla pods curing at Gaya. Of the three vanilla businesses that we visited, Gaya appears to be the most like a modern laboratory. If you're looking for jungle-grown vanilla, it's not at Gaya.

You might well ask, "How did vanilla get its name?" It was originally called xánat, by the Totonacos; the name in Náhuatl is tlilxóchitl. The Spanish name is vainilla, the diminutive of vaina, a pod. So vainilla–vanilla, in English–is a little pod. Even though most of us call it a vanilla bean, it is in no way related to phaseolus vulgaris, the common bean–pinto, black, navy, kidney, or any other you can think of, none of them and none of their relatives are related to vanilla. If you're asking for a vanilla bean in Spanish, the commonly used phrase is "ejote de vainilla".

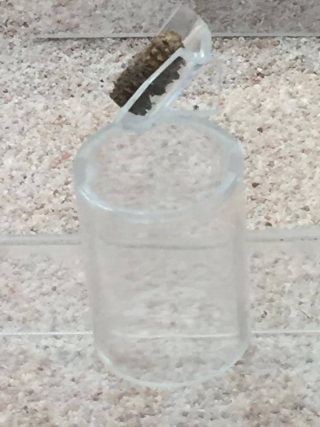

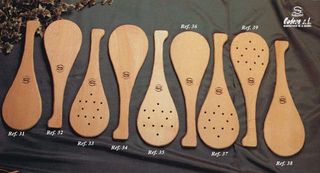

The store at Gaya. The company produces and sells the pods, natural vanilla extract, vanilla saborizante (flavoring), vanilla powder, sugar flavored with vanilla, coffee flavored with vanilla, vanilla liqueur, and some other products. We bought a few pods and some vanilla extract.

Our tour guide at Gaya gave us a good deal of information about what the vanilla vine requires to prosper, flower, and produce pods. Among the various details were:

–a warm, humid, tropical climate with temperatures ranging from 71 - 90 degrees Fahrenheit.

–more than 80% humidity.

–annual rainfall of 48 to 118 inches.

–location at zero to 600 meters above sea level.

–light at 80%.

–well-drained soil with pH between 6 and 7.

–plenty of organic material as its main nutrients.

March, April, and May are the time when new vanilla plants are cut and planted from older vines. From planting to first flowering, vanilla normally requires three years of growth. From pollination to harvest, each pod requires nine months to the day.

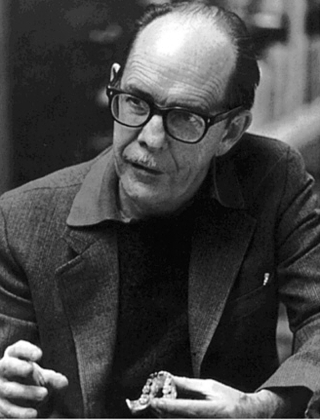

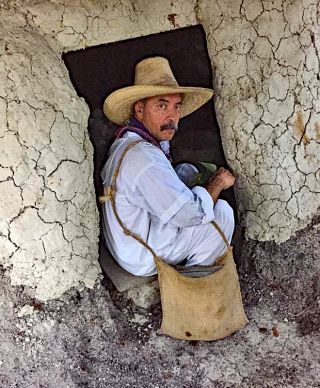

After visiting the installations at Gaya, we moved on to meet José Luis Hernández Decuir, of Eco-Park Xanath near Papantla. Sr. Hernández is a learned and really fascinating tour guide in all aspects of the traditional cultivation of vanilla. In the photo, he's sitting in the doorway to the temazcal (ancestral and spiritual sweat lodge) on his property.

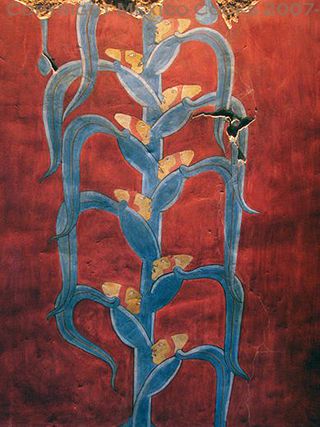

One of the most interesting facts about vanilla is its pollination. The early Spanish were fascinated with the plant, its flowers and pods, and its flavor. Of course they wanted to cultivate vanilla in Europe; Hernán Cortés introduced the plants there in the 1520s. The orchid plants grew and flowered, but produced no vanilla pods.

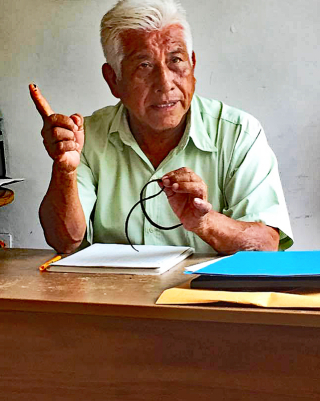

Sr. Hernández explains pollination of the vanilla orchid by the melipona bee. The clay pots in the photo are two tiers of bee hives balanced on bamboo shelves; the dark round spot on the top and bottom hives closest to Sr. Hernández are the tiny entryways to the hives.

Vanilla vines grow naturally in the jungles of Veracruz. Here, you can see two vanilla pods among the larger flat leaves of a tree-supported vine.

The Spaniards and other Europeans didn't know that in New Spain, the flower had a symbiotic relationship with the tiny, native melipona (stingless) bee. Only that bee is small enough to creep into the tiny hermaphroditic sex organs of the vanilla orchid and carry the pollen from the male to the female part of the flower; the melipona bee did not exist in Europe, although growers made efforts to import it. Outside Mexico, for three centuries no one could pollinate the orchid blooms and vanilla pods grew only in their country of origin.

The melipona stingless bee is tiny, measuring between approximately .07" and .5" in length. Photo courtesy Backyardnature.net.

In 1841, a simple and efficient artificial hand-pollination method was developed on Réunion Island in the French Indian Ocean, by a 13-year-old slave named Edmond Albius. His method is still used today. Using a beveled sliver of bamboo, an agricultural worker lifts the membrane separating the anther and the stigma inside the orchid flower; then, using his thumb, he transfers the pollen from the anther to the stigma. The flower will then produce a fruit. The vanilla flower lasts about one day, sometimes less, so growers have to inspect their plantations every day for open flowers, an extremely labor-intensive task. Today, vanilla is almost entirely pollinated by hand, still using this nearly 200-year-old method.

Our last specifically vanilla-related stop in Papantla was at the offices of the Consejo Estatal de Productores de Vainilla Veracruzana (the Veracruz State Council of Vanilla Producers), where Council President don Crispín Pérez García toured us through the state vanilla cooperative. Above, don Crispín talks with us about some of vanilla's characteristics. The various people who educated us about many of the historic data about vanilla agreed on those points, but on other points there was tremendous disagreement. Legend and myth mixed with statistics and theories to the point that it was difficult to sort out truth from fiction. Everyone agreed, though, that vanilla is a marvelous pod with many, many uses. Don Crispín answered one of my questions by saying, "Ay señora, la vainilla es…pues, es…supernatural!" ("Vanilla is…is…supernatural!")

Every year, more than 1,500 Veracruz vanilla producers from the municipalities of Misantla, San Rafael, Tecolutla, Gutiérrez Zamora, Coatzintla, Coyutla, Zozocolco de Hidalgo, Tihuatlan and Papantla bring 450 to 500 tons (that's between 90,000 and 100,000 pounds per year) of freshly harvested, green vanilla pods to the Council offices to be cured by traditional heat and sun methods. All of the vanilla that will be produced each year in Veracruz is sold prior to its harvest, as buyers are willing to pay almost any price to ensure that they get what they need. Don Crispín told us, "Now that we have the Denominación de Origen (similar to the Appellation d'Origine, the certification granted to certain French geographical indications for wines, cheeses, butters, and other agricultural products), it's very easy for us to export vanilla. Mexican vanilla is the best, and not just because I say so. Those who buy from us say that it is, and with the price we sell it for, no one is complaining." In years gone by, green vanilla sold for between 30 and 40 pesos the kilo (2.2 pounds). The wholesale price for 2017 started at 200 pesos per kilo and is currently at 350 pesos per kilo.

Vanilla curing in the light and air of the afternoon. Consejo Estatal de Productores de Vainilla, Papantla, Veracruz. Photo courtesy Pamela Gordon.

Another tiny section of the many, many racks of curing vanilla at the Vanilla Council offices. Vanilla isn't dried; it's cured until it is fragrant and leathery. If you find some pods to buy, make certain that they aren't brittle. They should be quite flexible. Don Crispín told us that a ready-for-use vanilla pod can be used over and over again; he suggested using a whole pod to stir our morning coffee–and then he said, "Wipe it off and put it away to use again. It won't go bad and it will last a long time." He also mentioned putting a vanilla pod into a canister of sugar; left in the sugar for just a short time, the vanilla will flavor the entire contents of the canister–and again, it's reusable.

A close-up of some of the vanilla pods at the Council offices. These are nearly finished with the curing process. You can see that the pods are shiny and wrinkled, exactly the state you want for your own home use. Click on any photo for a larger view.

Next week, we'll do what we've been wanting to do for the last month of articles: EAT! Come with Mexico Cooks! to try traditional, regional Totonaco dishes. We had our socks knocked off, and so will you.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here to see new information: Tours