Most Mexicans eat traditional rosca de reyes (Three Kings' Bread) on January 6. Its usual accompaniment is chocolate caliente (hot chocolate), often made in the pre-Hispanic way–with boiling water, not milk. If you've ever wondered about the title of Laura Esquivel's book Like Water for Chocolate, this is the 'why' of the title.

The delightful Laura Esquivel with Mexico Cooks!, several years ago at a Mexico City museum opening.

The Día de los Reyes Magos (the celebratory Day of the Three Kings) falls on January 6 each year. You might know the Christian feast day as Epiphany or as Little Christmas. The festivities celebrate the arrival of the Three Kings at Bethlehem to visit the newborn Baby Jesus. In Mexico and some other cultures, children receive gifts not on Christmas, but on the Feast of the Three Kings: The Kings, not Santa Claus or even the Niño Dios (Baby Jesus) are the gift-givers, because legend tells us that they were the givers of the gold, frankincense, and myrrh that they carried to the Baby Jesus. Many, many children in Mexico still receive special gifts of toys from the Reyes (Kings) on January 6.

Typically, Mexican families celebrate the festival with a rosca de reyes (Three Kings' Bread). The size of the family's rosca varies according to the size of the family, but everybody gets a slice, from the littlest toddler to great-grandpa. Accompanied by a cup of chocolate caliente (hot chocolate), it's a great winter treat.

Here's a delicious-looking rosca on the table at home.

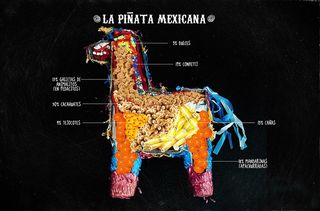

A few years ago, a chef friend explained a little about the significance of the rosca. He mused, "The rosca de reyes represents a crown; the colorful fruits simulate the jewels which covered the crowns of the Holy Kings. The Kings themselves signify peace, love, and happiness. The Niño Dios hidden in the rosca reminds us of the moment when Saint Joseph and the Virgin Mary hid the Baby Jesus in order to save him from King Herod, who wanted to kill him. The three gifts that the Kings gave to the Niño Dios represent the Kings (gold), God (frankincense), and man (myrrh).

"In Mexico, we consider that an oval or ring shape represents the movement of the sun and that the Niño Dios represents the Child Jesus in his apparition as the Sun God. Others mention that the circular or oval form of the Rosca de Reyes, which has no beginning and no end, is a representation of heaven–which of course is the home of the Niño Dios."

On January 4, 2019, the government of Soledad, San Luis Potosí, served an enormous rosca de reyes monumental, prepared jointly by bakeries from everywhere in the city.

In many places in Mexico, including Morelia, Michoacán, bakers prepare an annual monumental rosca for the whole city to share. The rosca prepared just a year ago in Morelia contained nearly 3000 pounds of flour, 1500 pounds of margarine, 10,500 eggs, 150 liters of milk, 35 pounds of yeast, 35 pounds of salt, 225 pounds of butter, 2000 pounds of dried fruits, and 90 pounds of candied orange peel. The completed cake, if stretched out straight, measured almost two kilometers in length! Baked in sections, the gigantic rosca was the collaborative effort of ten bakeries in the city. The city government as well as grocery wholesalers join together to see to it that the tradition of the rosca continues to be a vibrant custom.

The plastic Niño Dios (Baby Jesus) baked into our rosca a few years ago measured less than 2" tall. The figures used to be made of porcelain, but now they are generally made of plastic. See the dent from a bite on the Niño's head? Mexico Cooks! is the culprit. Every rosca de reyes baked in Mexico contains at least one Niño Dios; larger roscas can hold two, three, or more. Morelia's giant rosca normally contains 10,000 of these tiny figures.

Tradition demands that the person who finds the Niño in his or her slice of rosca is required to give a party on February 2, el Día de La Candelaria (Candlemas Day). The party for La Candelaria calls for tamales, more tamales, and their traditional companion, a rich atole flavored with vanilla, cinnamon, or chocolate. Several years ago, an old friend, in the throes of a family economic downturn, was a guest at his relatives' Three Kings party. He bit into the niño buried in his slice of rosca. Embarrassed that he couldn't shoulder the expense of the following month's Candelaria party, he gulped–literally–and swallowed the Niño.

El Día de La Candelaria celebrates the presentation of Jesus in the Jewish temple, forty days after his birth. The traditions of La Candelaria encompass religious rituals of ancient Jews, of pre-hispanic rites indigenous to Mexico, of the Christian evangelization brought to Mexico by the Spanish, and of modern-day Catholicism.

In Mexico, you'll find a Niño Dios of any size for your home nacimiento (nativity scene). Traditionally, the Niño Dios is passed down, along with his wardrobe of special clothing, from generation to generation in a single family.

The presentation of the child Jesus to the church is enormously important in Mexican Catholic life. February 2 marks the official end of the Christmas season, the day to put away the last of the holiday decorations. On February 2, the figure of Jesus is gently lifted from the home nacimiento (manger scene, or creche). His owners dress him in new clothing and gently carry him to the church, where he receives blessings and prayers. He is then carried home and rocked to sleep with tender lullabies, and is carefully seated in his very own throne or put away until the following year.

The Niño Dios Doctor from Puebla.

The Niño Dios dressed as a PEMEX employee–PEMEX is the monolithic petroleum company of Mexico. I took this picture while stopped for a fill-up during a trip to the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, in the southernmost part of Mexico.

Each family dresses its Niño Dios according to its personal beliefs and traditions. Some figures are dressed in clothing representing a Catholic saint particularly venerated in a family; others are dressed in the clothing typically worn by the patron saints of different Mexican states. Some favorites are the Santo Niño de Atocha, venerated especially in Zacatecas; the Niño de Salud (Michoacán), the Santo Niño Doctor (Puebla), and, in Xochimilco (suburban Mexico City), the Niñopan (alternately spelled Niñopa or Niño-Pa).

This Xochimilco arch and the highly decorated street welcome the much-loved Niñopa figure.

The veneration of Xochimilco's beloved Niñopan follows centuries-old traditions. The figure has a different mayordomo every year; the mayordomo is the person in whose house the baby sleeps every night. Although the Niñopan (his name is a contraction of the words Niño Padre or Niño Patrón) travels from house to house, visiting his chosen hosts, he always returns to the mayordomo's house to spend the night. One resident put it this way: "When the day is beautiful and it's really hot, we take him out on the canals. In his special chalupita (little boat), he floats around all the chinampas (floating islands), wearing his little straw hat so that the heat won't bother him. Then we take him back to his mayordomo, who dresses our Niñopan in his little pajamas, sings him a lullaby, and puts him to sleep, saying, 'Get in your little bed, it's sleepy time!" Even though the Niñopan is always put properly to bed, folks in Xochimilco believe that he sneaks out of bed to play with his toys in the wee hours of the night.

Trajineras (decorated boats) ready to receive tourists line the canals in Xochimilco. The best days of the week to go to Xochimilco are Saturdays and Sundays, when boating on the canals is a constant party.

Although he is venerated in many Xochimilco houses during the course of every year, the Niñopan's major feast day is January 6. The annual celebration takes place in Xochimilco's church of St. Bernard of Sienna. On the feast of the Candelaria, fireworks, music, and dancers accompany the Niñopan as he processes through the streets of Xochimilco on his way to his presentation in the church.

Gloria in Xochimilco with Niñopan, April 2008. Photo courtesy Colibrí.

Blue papel picado (cut paper decoration) floating in the deep-blue Xochimilco sky wishes the Niñopan welcome and wishes all of us Feliz Navidad.

El Día de La Candelaria means a joyful party with lots of tamales, coupled with devotion to the Niño Dios. For more about a tamalada (tamales-making party), be sure to read all about it in late January, right here on Mexico Cooks!.

From the rosca de reyes on January 6 to the tamales on February 2, the old traditions continue in Mexico's 21st Century.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.