If you have not yet read Part One of Mexico Cooks! visit to San Lorenzo Zinacantán, please see the article dated March 1, 2008.

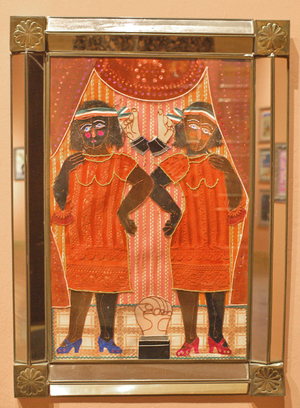

One of several Centros de Artesanía (craft stores) in the town of San Lorenzo Zinacantán, Chiapas.

As we drove into Zinacantán, we noticed many large invernaderos (greenhouses) here and there on the mountain slopes. In addition to the work of artesanía, there is a large

flower-growing industry in the town. Roses, daisies, chrysanthemums

and other flowers grow profusely in greenhouses that dot the hillsides

around this tiny town in a valley. The flowers are produced for use in the town as well as for export.

When Mexico Cooks! arrived in the town center, the parish church bells were ringing over and over again–Clang! Ca-CLANG! Clang! Clang! Ca-clang!–in a pattern that was neither the usual call to Mass nor the clamor (the mournful ring that indicates a parishioner has died). Although the Centros de Artesanía

(crafts centers) beckoned and we had really come to shop, we decided to

answer the call of the bells and visit the church first. Many

villagers crowded the entryway, watching one of the most beautiful

processions I’ve seen in Mexico. No photographs are permitted in

either the church atrium or the church itself, and I wished so deeply

that I had the talent to draw what we were watching.

Young men wearing white cotton shorts embroidered along the hems, thickly furry woven wool cotones, beribboned pañuelos

and straw hats processed from a shadowy side chapel carrying huge

wicker baskets filled to overflowing with every color rose petal. The

procession came slowly, these young zinacantecos scattering

thousands and thousands of petals throughout the candlelit main part of

the church. The wooden floor disappeared under a pink, yellow, red,

and white carpet. Other men wearing ritual black or white woolen cotones followed, stepping reverently on the rose petals, releasing their scent into the air along with the scent of copal burning in the clay incensarios (incense burners) they waved high above their heads.

Then followed twelve highly honored town elders dressed in even more

elaborate ritual clothing bearing three life-size statues on their

shoulders. The statues, each dressed in the finest ropa típica zinacanteca,

represented the Virgin Mary, Jesus, and San Lorenzo, the patron of

Zinacantán. The tremendous statues processed, crowned with gold and

surrounded by candles and artfully arranged flowers of every

description. The three saints gently tipped this way and that on the shoulders of their

bearers as they moved through the nave of the church.

The first young

men of the procession rained thousands more rose petals on the statues

as they wended their way slowly through the small church and back into

the half-light of the side chapel, where the saints were situated in

places of honor in front of the communion rail and altar.

This image, taken inside Templo Santo Domingo in San Cristóbal de

las Casas, Chiapas, shows candles similar to those lit before the

saints in Templo San Lorenzo, Zinacantán.

Beneath swooping banners, strings of brightly colored metal

ornaments, and tired-out balloons from prior fiestas, church elders lit

hundreds of candles to honor the three saints. Men clad in garments

resembling ribbon-festooned woolly black or white sheep hurried back

and forth placing candles in large stands, stopping to kneel and pray

aloud in Tzotzil. Meantime, women elders clad in brilliant blue and

teal embroidered chales (shawls) crouched on the church floor. Ritual white cotton rebozos covered

their heads and faces, leaving only their black eyes visible, watching

the men. The men lit candles and more candles. Young boys left

greenery around the statues. In the dimness, a solemn father pinched

his laughing son’s ear to remind him to respect the ceremony and the

saints.

When we could tell that the ceremony was drawing to a close, I asked

one of the elders to tell me its significance. "This is the first

Friday of Lent," he replied. "We’ll have this procession the first

Friday of every month from now until All Saints Day in November." He

smiled, bowed briefly, and moved away from me. My partner and I walked

slowly out of the church and back into the brilliant Zinacantán

afternoon light. We felt that we had been centuries and huge distances

away from this millennium. And of course, after that much mystical

time and space travel, we were starving. Lunch! Where would we have

lunch?

View of Zinacantán from the floor of the valley, 8500 feet above sea level.

Next week, read Part Three as Mexico Cooks! continues its visit to San Lorenzo Zinacantán, Chiapas.