Tostada Nexpa, opening course at the gala comida (main meal of the day) for dignitaries at the VI Encuentro de Cocina Tradicional de Michoacán (Sixth Annual Festival of Traditional Michoacán Cuisine).

Atápakua de verduras (creamy vegetable soup) and a miniature corunda wrapped in a corn leaf, second course at the festive comida.

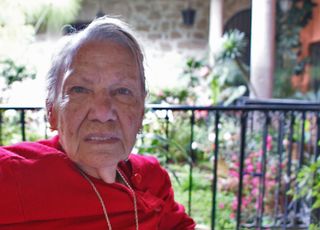

The VI Encuentro de Cocina Tradicional de Michoacán began on Friday, December 4, with a full day of academic conferences. During the course of the day, some of Mexico's top gastronomic experts spoke on topics ranging from the need to safeguard and promote Mexico's traditional cuisines to the importance of the teachings of Mexico's grandmothers. Among the speakers were Dra. Gloria López Morales (Mexico City), Lic. Olivia González (Querétaro), Inga. Magda Choque Vilca (Jujuy, Argentina), and Maestro Julián Estrada (Colombia).

The third course included (center) duck, locally hunted at Lake Pátzcuaro and prepared in salsa de chile guajillo; (left) Uruapan-farmed rainbow trout, covered in coconut and bathed in salsa de aguacate; and (right) turkey in salsa de manchamanteles (tablecloth-stainer), as served at traditional regional parties held on the day after a wedding.

Dra. Rubí Silva of Restaurante Los Mirasoles and Chef Lucero Soto Arriaga of Restaurante LU–two extraordinary Morelia restaurants serving regional Michoacán alta cocina mexicana (Mexican haute cuisine)–prepared an extraordinary menú de degustación (tasting menu) for participants' midday comida.

Uchepo de leche de elote tierno (sweet corn tamal with locally-grown and prepared mermelada de zarzamora (blackberry marmalade)–just one of the banquet's desserts.

Mexico Cooks!, once again in eager attendance at the annual

all-Michoacán traditional food festival, was honored and humbled to be

invited to participate as a judge for the 2009 culinary competitions. The competition cooking began early on Saturday morning, with judging for all categories starting at about noon. Assigned to judge traditional breads as well as candies and preserved fruits, Mexico Cooks! was glad to accompany a team of Mexico's finest chefs and food experts in making the rounds of the contestants in these categories.

Such a sacrifice in the name of research! This pyramid of preserved figs was one of the visual highlights of the sweets judging.

We judges were instructed to concentrate on the following categories for sweets:

- tradition

- use of basic ingredients from the region

- techniques of preparation

- techniques of preservation

- presentation

- flavors

- the cook's innovations or personal touches

Tejocotes en almibar (tiny crab apple-type fruit preserved in syrup) looked so beautiful in their cazuela de barro (clay cooking vessel). Tejocotes are in season in the winter. They're traditionally preserved in syrup or used as one of the many fruits in ponche navideño (Christmas punch).

Patricia de los Santos de la Cruz from Michoacán's westernmost coastal city, Lázaro Cárdenas, won the prize for the best sweet for her atole de plátano (thick drink made of ripe plantains). Made with coconut milk and very ripe plantains, this traditional atole, which contains no sugar or preservatives, could be either drunk from a cup or eaten with a spoon for dessert. We judges were delighted with its delicious flavor and smooth consistency.

For judging the bread category, we used the following criteria:

- tradition

- techniques of preparation

- texture

- flavor

- the cook's innovations or personal touches

A close contender for top honors in the bread category, these traditional quesadillas de miel de piloncillo (pastry with brown sugar syrup) are made by Sra. María Dolores Ocampo in Santa Ana Maya, Michoacán. She's the third generation of her family who bakes these crisp-crusted sweets, preparing them every other day. She told us that if we wanted to take some home, she would package them for us with the syrup in a separate bag so they wouldn't get soggy.

Beautiful folded pan dulce sprinkled with sugar made a marvelous visual impression but left something to be desired in its taste and texture.

Sr. Juvenal Acuña Baltierra brought a number of breads to the festival from his Chilchota bakery, Panadería La Favorita. We judges tasted a bit of each variety, but the minute we tried his pan de anís (anise bread, pictured at right in the photo) we knew what the bread category winner would be. Richly flavored with anise, sweet with piloncillo and with a texture both dense and chewy–but not heavy–this entry jumped out at all of us. It scored a big TEN (the best) in every judging class.

The other judging categories included moles, atápakuas, and corundas. We 26 judges managed to pick winners in every category, but it was a difficult job. The traditional cooks and bakers of Michoacán are marvelously talented and richly deserve the preservation efforts being extended to their art. One of the conference speakers, Maestra Jiapsy Arias, said it best: "La cocina se debe de preservar igual que cualquier pirámide." ('The kitchen must be preserved, just like any pyramid.')

We look forward to having you with us next December in Morelia for the seventh annual conference!

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.