The chefs and entire staff at Restaurante JASO combine close attention to every detail and every nuance of ambiance, service, wine, and innovative, creatively prepared food. Mexico Cooks! photo.

A little over a year ago, Mexico Cooks!' delightful friend Tony Chinn Anaya moved from Morelia to an apartment in Colonia Polanco, Mexico City. One day soon after the move, Tony emailed me to say, "You will not believe who our neighbors are: the chef/owners at JASO. The restaurant is fantastic! When can you come meet them?" It's taken me this long to get there. If I had understood way back then the fabulous experience that awaited me, I would have immediately asked Tony, "Is tomorrow too soon?"

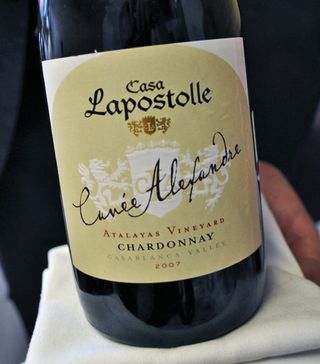

Our waiter began by presenting our wine (Casa Lapostolle Cuvée Alexandre Chilean Chardonnay, Atalayas Vineyard 2007), followed by a tray of six delicious and equally beautiful house-baked breads. The three breads pictured are (left) rye with nuts and raisins, (top) pumpkin, and (right) a heavenly herb-scented parmesan roll. The surprising detail: all of JASO's fresh butter (back right) is churned in the restaurant kitchens. The restaurant also pasteurizes its own milk and makes its own ice cream. Mexico Cooks! photo.

Chefs Jared Reardon and Sonia Arias met and fell in love while both were students at the Culinary Institute of America in Hyde Park, New York. The CIA at Hyde Park is the flagship of what is arguably the finest culinary school in the world, with three additional campuses in California, Texas, and Singapore. Chef Jared specializes in JASO's avant garde savories; Chef Sonia specializes in an extensive menu of glorious sweets. The twosome is unbeatable.

The light, citrus-y, cream-finished Chardonnay that we drank throughout our meal.

After stellar ten-year restaurant stints in the United States (Sonia: Daniel, Danube, and Bouley; Jared: New Orleans Marriott, Bouley, and others), the couple decided to live their restaurateurs' dream in Mexico City, Sonia's home. Sonia laughed, "He knew nothing about my culture except what he had seen when my family visited us in the States. Not just my mother and father, but the whole extended family came for holidays, graduations, and other special events. He thought we were all crazy, but this is how family lives in Mexico: loving, close, and unified. He loved it and wanted to see more of it, and even though I'd been in the United States for years, I was so happy to come home."

The entertaining and delicious appetizer: small house-baked cones filled with ceviche made from fresh raw tuna, seaweed, avocado, cucumbers, and fresh peaches, with a soy/lemon dressing. The black sesame seeds topping the ceviche imitate chocolate sprinkles. Photo courtesy Tony Anaya.

Chef Sonia selected a special multiple-course tasting menu for me and my dining companion, who else but Tony Anaya. Tony and I were doing just fine with the extensive small-portion meal until the desserts started appearing on the table. After the first two small dessert courses, we were groaning–but we couldn't stop without at least a taste of everything that the waiters brought us.

One of our several waiters pours puréed eggplant soup flavored with sun-dried tomato over grilled langostino. This is the only dish we tried that did not leave me craving another serving. Mexico Cooks! photo.

A single ravioli stuffed with rich foie gras, sauced with black truffles, adorned with thin ribbons of Venezuelan chocolate and shavings of parmesan cheese and accompanied by a fresh red raspberry. This, in my opinion, was the most memorable savory dish of the afternoon. Tony insisted that I not lick the dish, although I would have. That's why we had bread–to scoop up every bit of the sauce. Mexico Cooks! photo.

Chef Jared sources nearly all of the restaurant's ingredients in Mexico. The few exceptions include Kubata pork, which he purchases especially from an Iowa farm, and sweet corn, which is not grown commercially in Mexico. "The restaurant seats 120, and we serve between 70 and 100 clients per day. We recommend that our clients make reservations for cena (the evening meal), as the tables are usually filled at those hours."

Slices of rare duck breast crusted with Thai pepper, served over a seta mushroom and fresh seasonal vegetable risotto, sauced with cherry-laced port. Photo courtesy Tony Anaya.

Chef Sonia and I agreed that a true experience of fine dining at JASO's level is rare in Mexico. Wonderful food is definitely available everywhere here, from the most casual street stand to meals served in beautiful rooms, but Mexico has long been a culture of home-prepared meals and restaurants specializing in so-called 'Continental' cuisines. In recent years, Italian and Argentine restaurants have dominated the scene, with alta cocina mexicana just coming to the forefront. Four-year-old JASO brings a mix of ingredients to the arena, with high-end and obviously American influences predominating.

To cleanse our palates before dessert, our waiter presented us with tiny glowing cubes of house-made fresh orange gelatin balancing a quail's egg size scoop of Chef Sonia's guanábana sorbet. Photo courtesy Tony Anaya.

Confit de manzana con crujiente de nuez y helado de canela (sugar-preserved apple with crunchy nuts and cinnamon ice cream). In reality, this marvelously clever dessert was a deconstructed apple strudel a la mode! Mexico Cooks! photo.

I asked Chef Sonia why she chose repostería (desserts) as her specialty. "Ever since I was a little girl, just five or six years old, I have loved to bake. Even when I was that young, I begged to take courses in cake and cookie making instead of going to the movies with my little friends. I went to classes with women I thought of as old ladies–they were probably about the age I am now, but they seemed really, really old to me. I baked and baked, and even my sweets-loving family couldn't eat it all. I took the leftovers to school for my friends.

The tray of house-made bonbones de chocolate blanco (white chocolate marshmallows). I wanted to put five or six of these sinful delicacies in my pockets, but reason prevailed. Photo courtesy Tony Anaya.

"When I was still just a kid, everyone knew that if an occasion demanded a cake, I was the one to make it. When I was still in secundaria (middle school), I took a diplomado (degree course) in baking and pastry. I went to school from early in the morning till 2:30 in the afternoon. Then I came home and had a fast comida (main meal of Mexico's day) and was at the baking course from 4:00PM until ten at night. After that I had to do my regular homework and find time to sleep! My parents said I could keep doing it as long as I kept my grades up, and I did.

"My teacher in that baking course had been to the CIA and pushed me to go there, too. I filled out the application for a continuing education course in their summer school, and they accepted me. I don't know how I convinced my parents to let me go to New York at that age, but they finally said yes. When I got to the CIA, they took one look at me and said, 'You can't stay here! You are far too young, you have to go home.' I told them, 'My age was on the application, and you accepted me–I have to stay.' And I did stay, the youngest person there. I took classes all morning, took a double class in the afternoon, and helped the chefs. Trust me, my parents were not happy at all that I wanted to be a chef, but they let me go ahead. I took both an Associate of Arts and a Bachelor of Arts degrees at the CIA. Now, of course, my parents are in love with my career choice. Best of all, every day I get to live my passion for fine desserts."

To finish, a cappuchino and, to jog our memories, light-as-air madeleines dusted with powdered sugar. Mexico Cooks! photo.

The only dessert that we unfortunately devoured before taking a photo (it's possible that at that point we were all but comatose from our meal) was a rich, melting Belgian chocolate tarte served with mocha semifreddo and garnished with granules of expresso coffee. The tarte, exquisitely delicious, put us right over the edge into please-don't-bring-us-more-food territory.

Mexico Cooks! tours JASO's kitchen with Chef Jared. All kitchen photos courtesy Tony Anaya.

Chef Jared shops extensively at Mexico City's Mercado de Abastos (wholesale market), bringing cases of the freshest possible fruits and vegetables to the restaurant. Whatever is best at the market is used on the menu at JASO. He's always particularly interested in produce that is not farmed commercially; many vendors at the Abastos bring unusual items from rural areas. Ingredients not often seen elsewhere are found here, prepared in innovative ways for the most exacting palates.

Guillermo Mejía demonstrates the composition of the ceviche appetizer. He also bakes the cones to order (the shiny waffle cone apparatus is at the bottom of the photo).

They let me cook–better said, they let me stir!

Jesús Sánchez of the pastry team decorates a cake with fresh apple slices.

JASO's enormously talented pastry chef Sonia Arias with Mexico Cooks!. Both Sonia and Jared work twelve to fourteen hour days, six days a week. Sonia gets up extra-early every day to exercise "so I can keep up with the pastry guys–their stamina is amazing" and Jared spends a few hours several times a week at Mexico City's enormous Mercado de Abastos (wholesale market). Photo courtesy Tony Anaya.

The day we were at JASO was the grand opening of the restaurant's retail bakery. The restaurant supplies its special house-made desserts and ice creams to a few other Mexico City restaurants. In addition, JASO caters special events and will prepare its decadent and beautiful cakes to your order.

Pastry chef Sonía Arias, bubbling over about her completely outrageous cakes. Photo courtesy JASO.

The bakery, situated at the front of the house, has several tables created especially for enjoying JASO's incredible desserts with a coffee, a glass of port, or another drink of your choice. Mexico Cooks! photo.

Chefs Jared and Sonia have no plans to open another restaurant. "It's so important that we are both here to assure that every detail is right and every client has a wonderful experience," said Sonia. "I can't imagine trying to be in two places at once. With the restaurant and the bakery, plus the catering and special-order cakes we sell–life is full. We're happy and our clients are happy. That's what matters to us."

Just one of a pyramid of decadently chocolate JASO Bakery cupcakes. A new batch will be fresh out of the oven when you need a sweet Mexico City treat.

Restaurante JASO

Newton #88

Colonia Polanco

México, DF, México

Tel: 55.5545.7476

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.