Tamales in the tamalera (the steamer) at Tamalería (tamales shop) Méndez, on the street at the corner of Av. Baja California and Av. Insurgentes, Colonia Condesa, Distrito Federal. You can see that the tamalera is divided into three sections. Each section can hold a different kind of tamal (that's the word for ONE of a group of tamales). In this case, the tamales at the bottom left of the photo are Oaxaqueños (Oaxaca-style). On the right of the divider are tamales rojos (with a red chile sauce) and tamales de mole (both with pork meat). The third section of the tamalera holds just-out-of-sight tamales verdes (with chicken, in green chile sauce) and tamales con rajas y queso (with cheese and strips of chile poblano).

Older than

an Aztec pyramid and fresh as this morning’s breakfast, a pot of newly-steamed

tamales whets Mexico City’s appetite like nothing else in town. Dating to pre-Hispanic times—most historians

say tamales date to the time before the Christian era—the tamales of New Spain (now

Mexico) were first documented in the Florentine Codex, a mid-16th century

research project crafted by Spanish Franciscan monk Fray Bernadino Sahagún.

Traditionally, tamales are made by hand, not by machine. At first, they seem to be exhaustingly labor-intensive and difficult. Just as with most wonderful food, once you learn the techniques and tricks of making the various styles, they're not so hard to prepare–and they are so worth the time and effort! Here, Carmen Titita Ramírez Degollado, owner of Mexico City's Restaurante El Bajío, preparaes masa cocida (cooked corn dough) for her special tamales pulacles from Papantla, Veracruz.

The

ancients of the New World believed that humankind was created from corn. Just as in pre-history, much of Mexico’s traditional and

still current cuisine is based on corn, and corn-based recipes are still

creating humankind. A daily ration of corn

tortillas, tacos, and tamales keeps us going strong in the Distrito Federal,

Mexico’s capital city of more than twenty million corn-craving stomachs. Tamales are created from dried corn

reconstituted with builder’s lime and water.

The corn is then ground and beaten with lard or other fat into a thick,

smooth masa (dough). Filled with sauce and a bit of meat or

vegetable, most tamales are wrapped in dried corn husks or banana leaves and steamed, to fill Mexico

City’s corn hunger and keep her hustling.

Tamal-to-be: cut the banana leaf to the size and shape of the tamal you're making, then lightly toast each leaf. On the banana leaf, place a layer of masa, a strip of hoja santa (acuyo) leaf, and a big spoonful or two of cooked, shredded chicken in a sauce of chile guajillo, onion, and garlic.

Mexico’s capital city makes it easy to buy tamales any time the craving

hits you. Every day of the week, nearly

five million riders pack the Metro (the city’s subway system) and are disgorged

into approximately 200 Metro stations.

At any given Metro stop, a passenger is likely to find a tamales vendor. Her huge stainless steel tamalera (tamales steamer) hisses heartily over a low flame until

the tamales are sold out. Each steamer

can hold as many as two hundred tamales, and the vendor may preside over two or

three or more of these vats.

Titita folds the tamal so that the banana leaf completely wraps the masa and filling.

Hungry

students on the way to and from classes, office workers with no time to eat

breakfast at home, construction workers looking for a mid-morning pick-me-up:

all line up at their favorite vendor’s spot on the sidewalk closest to a

Metro exit. Near the vibrant

Chilpancingo Metro station at the corner of Av. Insurgentes and Av. Baja California, Sra. María de los Ángeles Chávez Hernández sells tamales out of two huge pots. “Qué le doy?”

(‘What’ll you have?’) she raps out

without ceremony to every hungry comer.

The choices: rojo (with pork and spicy red chile); verde (with chicken and even spicier

green chile); rajas con queso (strips

of chile poblano with melting white

cheese); mole (a thick spicy sauce

with a hint of chocolate); some Oaxaca-style tamales wrapped in banana leaves; and

dulce (sweet, usually either

pineapple or strawberry). The stand

sells about 200 tamales a day. Sra.

Chávez’s father, Ángel Méndez Rocha, has been selling tamales on this corner for

more than 60 years. Even at age 80, he alternates

weeks at the stand with his brother, selling tamales by the hundreds.

The masa and filling are centered in the banana leaf. Titita is simultaneously pressing the masa toward the middle of the leaf and folding each end of the banana leaf toward the middle.

The pair of tamales in the center of the photo are filled with chicken and chile guajillo sauce. The tamal closest to the bottom is made with black beans crushed with dried avocado leaves. Avocado leaves give a delicious anise flavor and fragrance to the beans. These tamales are ready to be steamed in the tamalera.

The tamal de chile guajillo, fresh out of the tamalera and unwrapped on my plate.

A specialty breakfast, unique to Mexico City, is the guajolota: a steaming hot tamal, divested

of its corn husks and plopped into a split bolillo,

a dense bread roll. Folks from outside

Mexico City think this combo is crazy, but one of these hefty and delicious

carbohydrate bombs will easily keep your stomach filled until mid-afternoon,

when Mexico eats its main meal of the day. When I asked Sra. Chávez Hernández about the name of the sandwich, she laughed. “Nobody knows why this

sandwich is called guajolota—the word

means female turkey. But everybody wants

one!”

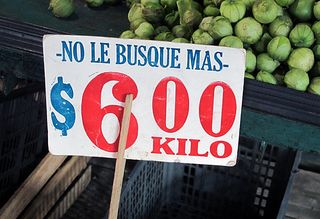

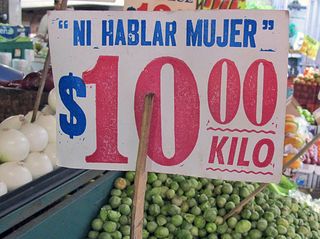

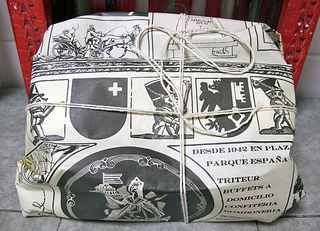

If you'd rather take your tamales home to eat them, Sra. Chávez of Tamalería Méndez or her employee, Sra. Lucina Montel, will gladly wrap them in paper and send them along in a bag.

For steaming tamales, the bottom portion of a tamalera is filled with water. Add a coin to the water and put the tamales vertically into the steamer, atop the perforated base that rests just above the water. When the water boils, the coin will rattle. When the rattle slows or stops, add more water.

Tamales can be a massive guajolota to eat on the street or the most delicate, upscale meal in a restaurant. These, prepared by chef Gerardo Vázquez Lugo of Restaurante Nicos, are a degustación (tasting) at the Escuela de Oficios Gastronómicos operated by online magazine Culinaria Mexicana, where chef Vázquez recently offered a workshop teaching the history, ingredients, and preparation of tamales. From left to right, the four tamales are: carnitas de pato en salsa de cítricos y chile chipotle (shredded duck confit in a citrus and chile chipotle sauce), tamal de tzotolbichay (with the herb chaya), tamal de mole negro (black mole),and tamal de frijol (beans).

Chef Gerardo Vázquez Lugo of Mexico City's Restaurante Nicos.

In

addition to being daily sustenance, tamales are a fiesta, a party.

In Mexico City and every other part of Mexico, Christmas isn’t Christmas

without tamales for the late-night family feasting on Christmas Eve. Gather the women of the family together, grab

the neighbors, and the preparation of tamales becomes a party called a tamalada. Mexico City chef Margarita Carrillo tells us,

“Mexican grandmothers from time immemorial say that the first ingredient for

great tamales is a good sense of humor.

Tamales like it when you sing while you prepare them, they love to hear a

little friendly gossip while you work, and if you make tamales in the good

company of your family and friends, they’re sure to turn out just the way you

want them: with fluffy, richly flavored corn dough on the outside and a delicious filling

on the inside.”

A small and elegant tamal de chocolate for dessert, prepared by Restaurante Nicos for the tamales workshop.

Señora Elia Rodríguez Bravo, specialty cook at the original Restaurante

El Bajío, strains masa cocida for tamales. She

gently shook a wooden spoon at me as she proclaimed, “You can’t make tamales

without putting your hands in the masa (corn

dough). Your hand knows what it

feels. Your hand will tell you when the masa is beaten smooth, when the tamales

are well-formed in their leaves, and when they have steamed long enough to be

ready to eat. Your hand knows!”

Señora María de los Ángeles Chávez Hernández (left) and her longtime employee Señora Lucina Montel (right) sell tamales at the street booth Tamalería Méndez seven days a week. They and Sra. Chávez's staff prepare hundreds of tamales every night, for sale the next day.

Let's go on a Mexico City tamales tour! Let Mexico Cooks! know when you're ready, and we'll be on our way.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.