When I was a little girl, a Popsicle was a big deal. Summertime meant that the ice cream truck, bell tinkling, would trundle through the neighborhood where I lived. After a frantic plea to Mom for money, she counted out coins and I raced to the corner where the rest of the kids were already gathered, waiting for the vendor to dig through his icy case for cherry, lime, or the reviled banana. The odor of amyl acetate (the chemical used for artificial banana flavoring) remains cloyingly in my memory. Photo courtesy ChezBeeper.

Remember? Hot summer days made those frozen snacks melt quickly, down childish fingers and the side of the hand, down the wrist and almost to the elbow in sticky trails of blood red and pale green. Nips of the cold treat slid in a chilly track from tongue to stomach, giving a few moments relief from childhood summers' heat and humidity. We didn't care that they were artificially flavored; Popsicles were a summer joy. Once I was an adult, I left them behind in favor of more sophisticated gelatos and sorbets.

Long before I dreamed of venturing to Mexico, Ignacio Alcázar of Tocumbo, Michoacán had a vision. Paletas—frozen treats similar to Popsicles—were on his mind. Tocumbo was a tiny village in the 1940s. Life there was harsh and subsistence was difficult. Eking a hardscrabble living from the sugar cane fields of the region around Tocumbo depended as much on Mother Nature's vagaries as on a farmer's backbreaking work. In those days, the pay for peeling 2,000 pounds of sugar cane was two pesos. Campesinos (field workers) could expect to earn a maximum of three pesos a week.

But making a living selling paletas depended solely on creating a desire for something delicious and refreshing to satisfy someone's antojo (whim). In the mid-1940s, Ignacio Alcázar, his brother Luis, and their friend Agustín Andrade left the misty mountains and pine forests of Michoacán and headed for Mexico City, the country's burgeoning hustle-bustle capital. The men had made paletas in Tocumbo for several years, but it was time to try their hand in the big city.

In 1946, the three men, illiterate native sons of Tocumbo, established an ice cream shop in downtown Mexico City. The new paletería (paleta shop) wasn't elegant, but it worked. People clamored for more and more paletas. The Alcázar brothers and Andrade expanded, and expanded again. They sold franchise after franchise of their paleta brainchild to their relatives, friends, and neighbors from Tocumbo. The single shop that the two men started became the most successful small-business idea in Mexico in the last half century, known across the country as La Michoacana. More than 15,000 La Michoacana outlets currently exist around Mexico, most of them owned by people from the town of Tocumbo.

Mexico City alone has more than 1,000 La Michoacana outlets. Usually the paleterías are called La Michoacana, La Flor de Michoacán or La Flor de Tocumbo. Every Mexican town with more than 1,000 residents is without one. Only Pemex, the nationalized petroleum company, has blanketed Mexico so completely.

When I moved to Mexico in 1981, a Mexican friend insisted that she was going to buy me a paleta. "A Popsicle?" I scoffed. She took me by the scruff of the neck and all but shoved me into the nearest La Michoacana. I peered into the freezer case and was amazed to see hundreds and hundreds of rectangular paletas, organized flavor by flavor, lined up in stacks in their protective plastic bags.

And what flavors! Mango (plain or with chile), blackberry, cantaloupe, coconut, guava, and guanábana (soursop) were arranged side by side with strawberry, vanilla, and—no, that brown one wasn't chocolate, it was tamarindo. Some were made with a water base and some with a milk base. Every single paleta was loaded top to bottom with fresh fruit. There was nothing artificial about these. I was hard pressed to decide on just one flavor, but I finally bit into a paleta de mango and was an instant addict.

The story of the paleteros (paleta makers) from Tocumbo piqued my curiosity. For many years I've been determined to visit this out-of-the-way town. I finally made the trip to the place where it all started. Getting to Tocumbo isn't simple, but driving the two-lane back roads winding along green mountains is lovely.

The names of the towns I passed through (Tarácuato, Tlazazalca, Chucuandirán, Tinguindín) roll off the tongue in the ancient rhythmic language of the Purhépecha (Michoacán's indigenous people). Women, teenage girls, and children wear beautiful ropa típica (native dress) as they walk to market or gather wood in the hills. Fragrant wood smoke mixes in the air with the crisp scent of pine. Wildflowers dot the roadsides and mountains with purple, orange, yellow and blue.

The well-manicured entrance to the town of Tocumbo lets you know immediately that you have arrived. No statues of Miguel Hidalgo or Benito Juárez grace the junction, nor is there a proud plaque commemorating a favorite local hero. Instead, the townspeople have erected a two-story statue of (what else?) a paleta. I'd seen photos of the monument, but the actual sight of the huge frozen delight made me laugh out loud.

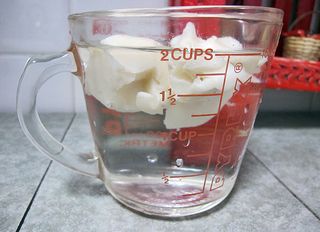

Strawberry cream paletas.

Carefully trimmed trees, flowers, and lawns edge both sides of the road into town. Large, well-appointed homes line the streets and the local trucks and cars are recent models and very well maintained. Tocumbo has one of the highest per capita incomes of any town in Mexico.

My first stop was at the Tocumbo parroquia (parish church). Named in honor of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, the church is modern and beautifully adorned with stained glass. The architect who designed the church is Pedro Ramírez Vázquez. Arquitecto Ramirez also designed some of Mexico's most famous buildings, including the Basílica of our Lady of Guadalupe, the 1968 Olympic Games installations, Aztec Stadium, the National Anthropology Museum and the National Medical School buildings, all in Mexico City. Arquitecto Ramírez, born on April 16, 1919, died on April 16, 2013. His passing is a huge loss to the world's architectural community.

Ramírez was one of the most outstanding building designers in Mexico, a man who enjoyed international fame for his creations. It's particularly telling of the economic power of the town that the people of Tocumbo contracted with him to design their parish church.

As I sat for a bit in the town plaza, two local women strolled across the square eating paletas. After we greeted one another, I asked who the best person in town would be to give me local history. They directed me to the mayor's office on the other side of the plaza.

I spent several hours at the Tocumbo mayor's office talking with town official German Espinoza Barragán, who told me long stories of life and times in Tocumbo, and the history of the paleta.

Sr. Espinoza mentioned that many people erroneously believe that all La Michoacana stores throughout Mexico are owned by one family. "You already know that the founders were Ignacio Alcázar, his brother Luis, and their friend Agustín Andrade, and that they sold the first La Michoacana franchises to their relatives and friends. After that, the relatives and friends sold franchises to their relatives and friends, and the business just continued to spread. With a simple formula of handmade products produced every day and sold inexpensively, the business has produced hundreds of jobs as well as a high standard of living that's different from any other town in the region."

Sr. Espinoza commented, "All of our streets are paved, and all have street lights. People live very well here, although it's difficult to say how many actually do live here year round."

I looked up from my notes. "Why is that?"

"A lot of tourists from all over Mexico and many other countries pass through this town," he began. "Many see that our life here is peaceful, our climate perfect, and our town beautiful, so they ask about renting or buying a house here. Once they see Tocumbo, everyone wants to stay."

I nodded in agreement. The thought had occurred to me.

Sr. Espinoza nodded too. "People say, 'Find me a house to rent.' I just tell them to forget it, it's hopeless. Then they tell me, 'But so many of the houses here in town are vacant! Surely the owners would like to rent their houses.' I shake my head, even though up to 75 per cent of the houses here in Tocumbo are vacant for eleven months of the year.

"The thing is, everyone comes home at Christmas. No matter whether so-and-so's family lives all year round in Chiapas or Tijuana working in their La Michoacana store, in December everyone is here. Where would they stay, if their houses were rented?

"During the 1990 census, INEGI (the Mexican census bureau) tried to count the number of people in town. They counted about 2,400 people. But truly, triple that number call Tocumbo 'home'. No one misses the holiday season here. They come home to tell their stories, to find out the last word in the business, to look for a girlfriend, to get married, to have quinceañeras (a girl's15th birthday celebration), to baptize their babies. They put off all of these festivities for months, until the winter low season for selling paletas arrives and they can come home.

"This year, the Feria del Paletero (Fair of the Paleta Maker) starts on December 22 and ends on December 30. There will be sports events, free paletas, rides for kids and adults, and other things for everyone to do. You should come."

"The success of the Tocumbo paleta business must inspire people all over Mexico," I commented.

Once again Sr. Espinoza nodded. "It's a kind of work that offers even the person with the least schooling a way to make a good living, without going to work in the United States and without getting involved in selling illegal drugs."

He returned to the history of the business. "Of course, word of the success of the new paleta business in Mexico City reached Tocumbo really fast. All Tocumbo packed its suitcases and went to get in on the gold mine. Everybody was buying paleta stores. And the best is, all the contracts were made on the solid word of the parties, without any paperwork, and all the loans to start the businesses were made between the buyers and the sellers. No banks were involved.

"This first generation of paleteros (paleta makers) felt the obligation to let everyone have a part of the success. Remember that Tocumbo is a very small town. Almost everyone is related to everyone else. Everyone of that generation had grown up together, and everyone shared just a few last names. The belief was 'today it's your turn, tomorrow it's mine'. And everyone lived by that.

"Today, things are a little different, but only a little. There's still room for all the paleterías in Mexico, and the majority belong to Tocumbans. Even though other ice cream stores like Bing and Dolphy have opened and there are even new brands coming in from the United States, there's no other big success like we have had. To start with, the paleta is the people's business, not corporate business. Other businesses might spend huge amounts of money on advertising and special wrappings, but we Tocumbans don't run our businesses that way. We're flexible, we save our money, and we work very hard. The paleterías are open from early in the morning till late at night, every day of the year. Even when the owners are home for the holidays, their employees are working in the stores. We make only as many paletas as we can sell each day. We don't use chemicals in our paletas, and we adapt the flavors to the regions where our stores are."

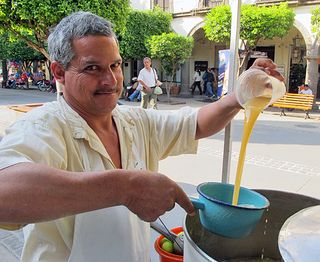

The orange paletas are mango. Click to enlarge the photo and you'll easily see the chunks of fresh-frozenfruit.

Sr. Espinoza went on to tell me that the most popular flavor paleta is mango, because it's the fruit that everyone in Mexico loves. He continued, "In the south of Mexico, we have to offer mamey, zapote, and plátano. Where people have more income, we can sell a paleta for seven pesos. Where income is lower, such as in the states of Chiapas and Oaxaca, we sell a paleta for five pesos. We keep our stores very simple, so everyone can feel comfortable to come inside. And we try to open our stores in places where lots of people congregate: near schools, near hospitals, and near sports facilities."

The story of this business amazed me. I shook my head and said, "What was the next step for the paleteros?"

"When we saw that so many Mexicans were living in the United States, the next logical move was to start stores there. We started moving there too, and opened the first shops in California, Texas, Arizona, and Florida. And now—now there are La Michoacana stores in Pennsylvania, in Chicago, and in New York. Next will be Central and South America, you'll see.

"Did you look at the monument at the entrance to town?" Sr. Espinoza asked me. "Of course! It's wonderful," I exclaimed.

"On the way out of town, look at it again," he said. "Look, a little drawing of it is on my business card." He handed me the card. "See the blue ball of ice cream in the paleta? And see the paletas all over the ball?" I did see them. "The blue ball represents the earth, and the bright colored paletas cover it." He smiled at me. "And someday, paletas from Tocumbo, Michoacán will truly cover the globe."

I have absolute faith that he's right.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.