Emblematic of Oaxaca: chocolate caliente (hot and foamy hand-ground hot chocolate) prepared in water and served in a bowl. Zaachila market, Oaxaca.

There's much more to Oaxaca's magic than simply its capital city, which is of course fantastic in its own right. Driving in any direction from the city, twisting two-lane roads lead to small towns; each town has a weekly market, and each market has beauties of its own.

At the Zaachila Friday market, a vendor sold calabaza en tacha (squash cooked in brown sugar syrup) covered with a leaf to keep insects away and maintain the squash fresh and ready to eat.

Another vendor offered flor de frijolón (the red flowers of a large, black, local bean known elsewhere as ayocote negro).

Tejate, Oaxaca's emblematic cold, foamy, and refreshing chocolate beverage, scooped out of this clay bowl with a red-lacquered jícara into the size cup you prefer: small, medium, or large.

When Mexico Cooks! traveled recently to Oaxaca, joyous anticipation and a letter of introduction were stowed among my baggage. For years I had read about and admired (albeit from afar) Abigail Mendoza Ruiz and her sisters, but we had never met. This trip would fix that: two days after my scheduled arrival, we had an appointment for comida (Mexico's main meal of the day) at the Mendoza sisters' Restaurante Tlamanalli in Teotitlán del Valle. The restaurant's name, a Náhuatl word, means several things: it's the name of the Zapotec kitchen god, it means abundance, and it means offering. For me, newly arrived in Teotitlán del Valle, the word Tlamanalli meant, 'you are about to have the experience of a lifetime'.

Teotitlán del Valle is best known as the principal Oaxaca rug-weavers' town. Among its five to six thousand inhabitants, the majority weaves wool to make lovely rugs and also combines the weaver's tasks with agricultural work, growing both marketable and personal-use corn and other vegetables plus raising poultry for personal use.

Detail of the rustic wooden rueca (spinning wheel) used by the Teotitlán del Valle rugmakers for spinning fine wool yarns.

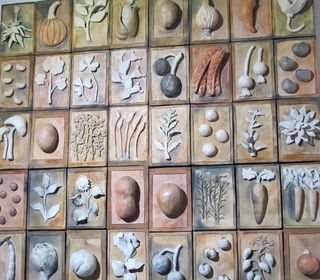

Shown in this group of Oaxaca-made baskets: a flat double comb for carding wool, a pointed spindle, and various natural coloring agents, along with hanks of wool which demonstrate just a few of the colors used in Oaxacan wool rugs.

Not only are the Mendoza Ruiz sisters extraordinary regional cooks, they and their siblings are also well-known rug weavers. Their parents, Sra. Clara Ruiz and don Emilio Mendoza (QEPD), gave this world a group of supremely gifted artisans, all of whom learned the weavers' traditions at their parents' knees.

Abigail Mendoza started learning kitchen traditions as a five-year-old, as the first daughter of the family, watching her mother grind nixtamal (dried native corn soaked and prepared for masa (dough). In the postcard above, the little girl (who is not Abigail) watches seriously as the woman we imagine to be her mother pats a tortilla into its round shape.

By the time she was six years old, Abigail was in charge of sweeping the kitchen's dirt floor, gathering firewood, and making the kitchen fire. At age seven, she told her mother, "I'm ready to grind corn on the metate," (volcanic rock grinding stone, seen in the center of the photograph above), but she wasn't yet strong enough to use her mother's large stone. She was barely able to lift its metapil (stone rolling pin). She eagerly awaited the purchase of a metate small enough for her use. Doña Clara taught her to grind the home-prepared nixtamal, pat-pat-pat the tortilla dough into perfect thin rounds, and bake them on the comal (wood-fired griddle made of clay).

Abigaíl Mendoza Ruiz, the internationally known and much-traveled Zapoteca cook, best loves preparing meals in her home kitchen and her restaurant kitchen in Teotitlán del Valle, Oaxaca. Here, she's pictured in the beautiful open kitchen of Tlamanalli, the restaurant where she and her sisters Rufina and Marcelina (pictured above) create their culinary alchemy.

Abigail Mendoza is at once filled with light and filled with mystery. Luminous as her joy-filled personality, her smile lights up any room she enters. She is a woman of deep faith, a subscriber to the mysteries of dreams, a believer in spirit worlds both before and after life, a strong believer both in human relationships along life's horizontal and the vertical relationship of God with humanity. Formally educated only through primary school, she holds intense wisdom borne of deep meditation on the nature of life, both spiritual and physical.

In her extraordinary book Dishdaa'w, Abigail reveals her life story, her philosophies, and a good part of her soul. The Zapotec title of her biography (transcribed and organized by Concepción Silvia Núñez Miranda) means "the word woven into the infinite meal". And what does that mean? Food itself has a soul, the soul is transmitted in food's preparation and its ingestion. We are all part of the whole, and the whole is part of each of us.

In her restaurant's large kitchen, Abigail is the sun itself. Hair braided with traditional Zapotec ribbons into a royal crown, she's holding a fistful of freshly picked flor de calabaza (squash flowers).

What did we do, Señorita Abigail and I? We talked, we laughed, we discovered who our many friends in common are, we swapped kitchen lore and recipes, we gossiped (just a little, and in the best possible way), and we each felt like we had met yet another sister, a sister of the kitchen.

And then she asked what we would like to eat. After stumbling around in a maze of I-don't-know-what-to-request, I suggested that she simply bring us her personal choices from the day's menu.

Menu for the day, Restaurante Tlamanalli. The dishes are not inexpensive, but ye gods: save up, if you must, and go. You will never regret it.

First came made-on-the-spot creamy guacamole, in tiny turkey-shaped clay dishes and accompanied by a small bottle of local mezcal amd a wee dish of roasted, seasoned pepitas (squash seeds).

Mole zapoteco con pollo (Zapotec-style mole with chicken). Each of our dishes was accompanied by freshly made tortillas, hot from the comal (griddle).

Pre-hispanic segueza de pollo (breast of chicken in tomato and chile sauce with dried corn and hoja santa). If I should ever be in Oaxaca and in a position to choose one last meal, this would be it.

The herb hoja santa is added to the sauce just before serving and gives a delicate anise flavor to the segueza de pollo.

Oaxaca's heirloom jitomate riñón (kidney-shaped tomatoes) is used for creating the intense and deeply tomato-flavored sauce for the segueza.

When we finished our meal, the Mendoza sisters and doña Clara invited Mexico Cooks! to visit their private kitchen altar, devoted to the Preciosa Sangre de Cristo (Precious Blood of Christ), whose feast day is a major holiday in Teotitlán del Valle and for whom the parish church is named. The home altar has offerings of seasonal fruits as well as perpetually-burning candles.

Mexico Cooks! will go back to Oaxaca, back to Teotitlán del Valle, and back to Restaurante Tlamanalli. After all, I want to visit my new sister–she's a constant inspiration and the best Oaxacan cook I know.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.