Originally published in a different format in 2007, this article has recently received a good bit of attention on social networks. It bears re-publishing here.

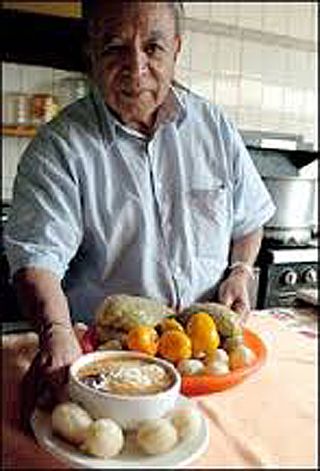

"Real" Mexican chile relleno (stuffed, battered, and fried chile poblano), caldillo de jitomate (tomato broth), and frijoles negros (black beans).

More and more people who want to experience "real" Mexican food are asking about the availability of authentic Mexican meals outside Mexico. Bloggers and posters on food-oriented websites have vociferously definite opinions on what constitutes authenticity. Writers' claims range from the uninformed (the fajitas at such-and-such a restaurant are totally authentic, just like in Mexico) to the ridiculous (Mexican cooks in Mexico can't get good ingredients, so Mexican meals prepared in the United States are superior to those in Mexico).

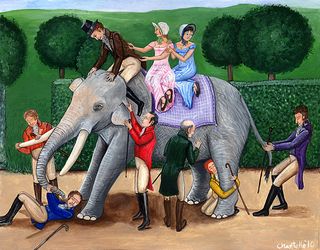

Much of what I read about authentic Mexican cooking reminds me of that old story of the blind men and the elephant. "Oh," says the first, running his hands up and down the elephant's leg, "an elephant is exactly like a tree." "Aha," says the second, stroking the elephant's trunk, "the elephant is precisely like a hose." And so forth. If you haven't experienced what most posters persist in calling "authentic Mexican", then there's no way to compare any restaurant in the United States with anything that is prepared or served in Mexico. You're simply spinning your wheels.

It's my considered opinion that there is no such thing as one definition of authentic Mexican. Wait, before you start hopping up and down to refute that, consider that "authentic" is generally what you were raised to appreciate. Your mother's pot roast is authentic, but so is my mother's. Your aunt's tuna salad is the real deal, but so is my aunt's, and they're not the least bit similar.

Carne de puerco en salsa verde (pork meat in green sauce), my traditional recipe.

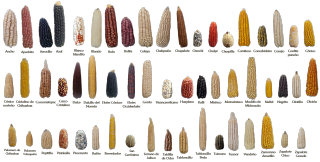

The descriptor I use for many dishes is 'traditional'. We can even argue about that adjective, but it serves to describe the traditional dish of–oh, say carne de puerco en chile verde–as served in the North of Mexico, in the Central Highlands, or in the Yucatán. There may be big variations among the preparations of this dish, but each preparation is traditional and each is authentic in its region.

I think that in order to understand the cuisines of Mexico, we have to give up arguing about authenticity and concentrate on the reality of certain dishes.

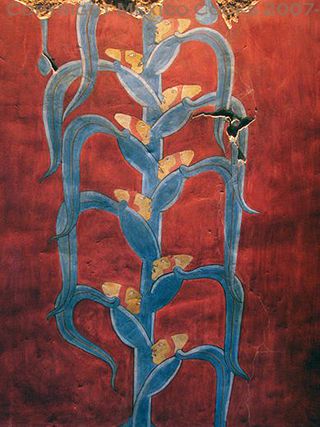

A 200-year-old tradition in Mexico at this time of year: chiles en nogada (stuffed chiles poblano in a creamy sauce made with fresh (i.e., recently harvested) walnuts. It's the Mexican flag on your plate: green chile, white sauce, and red pomegranates.

Traditional Mexican cooking is not a hit-or-miss let's-make-something-for-dinner proposition based on "let's see what we have in the despensa (pantry)." Traditional Mexican cooking is as complicated and precise as traditional French cooking, with just as many hide-bound conventions as French cuisine imposes. You can't just throw some chiles and a glob of chocolate into a sauce and call it mole. You can't simply decide to call something Mexican salsa when it's not. There are specific recipes to follow, specific flavors and textures to expect, and specific results to attain. Yes, some liberties are taken, particularly in Mexico's new alta cocina (haute cuisine) and fusion restaurants, but even those liberties are based, we hope, on specific traditional recipes.

In recent readings of food-oriented websites, I've noticed questions about what ingredients are available in Mexico. The posts have gone on to ask whether or not those ingredients are up to snuff when compared with what's available in what the writer surmises to be more sophisticated food sources such as the United States.

Deep red, vine-ripened tomatoes, available all year long in central Mexico. The sign reads, "Don't think about it much–take a little kilo!" At twelve pesos the kilo, these tomatos cost approximately $1.00 USD for 2.2 pounds.

Surprise, surprise: most readily available fresh foods in Mexico's markets are even better than similar ingredients you find outside Mexico. Foreign chefs who tour with me to visit Mexico's stunning produce markets are inevitably astonished to see that what is grown for the ordinary home-cook user is fresher, more flavorful, more attractive, and much less costly than similar ingredients available in the United States.

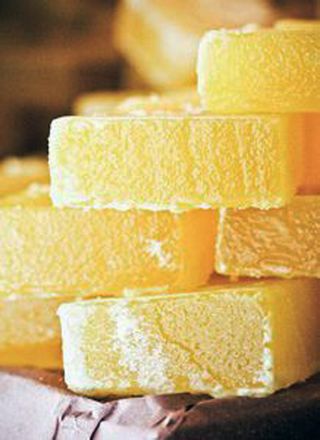

Chicken, ready for the pot. Our Mexican chickens are generally fed ground marigold petals mixed into their feed–that's why the flesh is so pink, the skin so yellow, and the egg yolks are like big orange suns.

It's the same with most meats: pork and chicken are head and shoulders above what you find in North of the Border meat markets. Fish and seafood are from-the-sea fresh and distributed within just a few hours of any of Mexico's coasts.

Nevertheless, Mexican restaurants in the United States make do with the less-than-superior ingredients found outside Mexico. In fact, some downright delicious traditional Mexican meals can be had in some North of the Border Mexican restaurants. Those restaurants are hard to find, though, because in the States, most of what has come to be known as Mexican cooking is actually Tex-Mex cooking. There's nothing wrong with Tex-Mex cooking, nothing at all. It's just not traditional Mexican cooking. Tex-Mex is great food from a particular region of the United States. Some of it is adapted from Mexican cooking and some is the invention of early Texas settlers. Some innovations are adapted from both of those points of origin. Fajitas, ubiquitous on Mexican restaurant menus all over the United States, are a typical Tex-Mex invention. Now available in Mexico's restaurants, fajitas are offered to the tourist trade as prototypically authentic.

You need to know that the best of Mexico's cuisines is not found in restaurants. It comes straight from somebody's mama's kitchen. Clearly not all Mexicans are good cooks, just as not all Chinese are good cooks, not all Italians are good cooks, etc. But the most traditional, the most (if you will) authentic Mexican meals are home prepared.

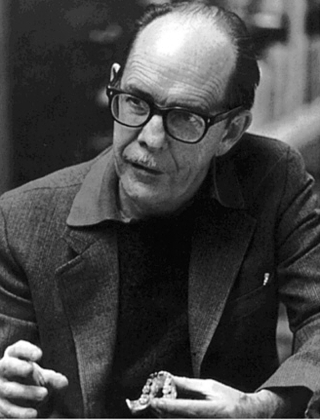

Diana Kennedy, UNAM 2011. Mrs. Kennedy was at the Mexican Autonomous University to present her book, Oaxaca Al Gusto.

That reality is what made Diana Kennedy who she is today: she took the time to travel Mexico, searching for the best of the best of the traditional preparations. For the most part, she didn't find them in fancy restaurants, homey comedores (small commercial dining rooms) or fondas (tiny working-class restaurants). She found them as she stood next to the stove in a home kitchen, watching Doña Fulana prepare comida (the midday main meal of the day) for her family. She took the time to educate her palate, understand the ingredients, taste what was offered to her, and learn, learn, learn from home cooks before she started putting traditional recipes, techniques, and stories on paper. If we take the time to prepare recipes from any of Ms. Kennedy's many cookbooks, we too can experience her wealth of experience and can come to understand what traditional Mexican cooking can be. Her books will bring Mexico's kitchens to you when you are not able to go to Mexico.

Fresh Michoacán-grown strawberries, available all year in central Mexico.

In order to understand the cuisines of Mexico, we need to experience their riches. Until that time, we can argue till the cows come home and you'll still be just another blind guy patting the beast's side and exclaiming how the elephant is mighty like a wall.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours