Some of the many varieties of beans for sale at the daily indigenous market in San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas. The metal cup measures one kilo (2.2 pounds).

The Spanish word frijol is a bastardization of ancient Spanish frisol, which itself is a rendering of the Catalán word fesol–which comes from the Latin scientific name–are you still with me?–phaseolus vulgaris. Is that more than you wanted to know about bean nomenclature?

Here's yet another little bit of Mexican bean esoterica: in Mexico, when you go to the store or the tianguis (street market) to buy beans, you are buying frijol. When you prepare the frijol at home, the cooked beans become frijoles. That's right: raw dried beans in any quantity: frijol. Cooked beans, frijoles. If you ask a tianguis vendor for a kilo of frijoles, he could rightfully send you to a restaurant to make your purchase.

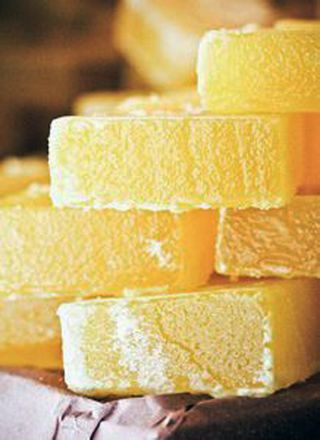

The simple utensils you need to cook dried beans: an olla de barro (clay pot) and a strainer. You can also use a heavy metal pot, or a pressure cooker, but the clay pot adds special flavor to the cooked beans. These pale yellow, long-oval beans are frijol peruano (Peruvian beans, or phaseolus vulgaris), the most commonly used bean in the Central Highlands of Mexico. A clay bean pot has been fired at a temperature substantially higher than the heat of your stove burner, so there's no need to worry about it breaking when you use it to cook.

Mexico Cooks! loves beans. In our kitchen, we prepare about a pound of dried beans at a time. After cooking, this is enough frijoles de la olla (cooked-in-the-pot beans) to serve, freshly cooked, for a meal or two, with plenty left over to freeze. We freeze the rest of the cooked beans in five or six two-portion size plastic sandwich bags. Cooked beans and their pot liquor freeze very well.

I found this little batch of rocks, discolored or very wrinkled beans, and other garbage in the half-kilo of frijol that I cooked yesterday.

Beans are very easy to cook. First, pick carefully through your beans. Even if you buy bulk beans or commercially packaged dry beans at a modern supermarket, be certain to pick through them and discard any beans that look badly broken, discolored, or wizened, as well as any small rocks. You may also find pieces of straw, pieces of paper, and other detritus in any purchase of beans. Put the cleaned beans in a strainer and wash well under running water.

To soak, or not to soak? Some folks recommend soaking beans for up to 24 hours to shorten their cooking time, but Mexico Cooks! has tried both soaking and not soaking and has noticed that the cooking time is about the same either way. We never soak. You try it both ways, too, and report back with your findings.

Epazote (wormweed) grown in a maceta (flower pot) on my terrace. Just before turning on the fire to cook the beans, Mexico Cooks! adds two sprigs of epazote, just about this size, to the pot of beans and water. The strong, resinous odor of the herb absorbs almost entirely into the beans, giving them a mild flavor punch and, some say, diminishing flatulence.

My olla de barrlo (clay bean pot) holds about a half kilo of frijol plus enough water to cook them. You can see the light glinting off the water line, just below the top part of the handle. If you don't have an olla de barro, a heavy metal soup pot will do almost as well. The clay does impart a subtle, earthy flavor to beans as they cook.

Over a high flame, bring the pot of beans to a full, rolling boil. Turn the flame to a medium simmer and cover the pot. Allow the beans to cook for about an hour. At the end of an hour, check the water level. If you need to add more water, be sure that it is boiling before you pour it into the bean pot; adding cold water lowers the cooking temperature and can cause the beans to toughen. Continue to cook the beans at a medium simmer until, when you bite into one, it is soft and creamy. The pot liquor will thicken slightly.

Now's the time to salt your beans–after cooking, not before and not during. We use Espuma del Mar (Mexican sea salt from the state of Colima) for its wonderful sweetly salty flavor, but any salt will do. Add a little less salt than you think is correct–you can always add more later, and you don't want to oversalt your beans.

If you live in the United States or Canada, you'll want to order the fabulous heritage dried beans sold by Rancho Gordo. Rancho Gordo's owner, my friend Steve Sando, has nearly single-handedly brought delicious old-style beans to new popularity in home and restaurant kitchens. If you've tasted ordinary beans and said, "So what?", try Rancho Gordo beans for a huge WOW! of an eye opener.

Mexico Cooks! likes frijoles de la olla (freshly cooked beans, straight from the pot) with a big spoonful of salsa fresca (chopped tomato, minced onion, minced chile serrano, salt, and roughly chopped cilantro). Sometimes we steam white rice, fill a bowl with it, add frijoles de la olla and salsa fresca, and call it comida (main meal of the day).

Chiles serranos and manteca (lard)for frijoles refritos estilo Mexico Cooks!.

For breakfast, Mexico Cooks! prepares frijoles refritos (refried beans). Served with scrambled eggs, some sliced avocado, and a stack of hot tortillas, they're a great way to start the morning. A dear friend from Michoacán taught me her way of preparing refried beans and I have never changed it; people who say they don't care for refried beans eat a bite, finish their portion, and ask for seconds. They're that good.

Here's some more bean trivia: frijoles refritos doesn't really mean 'refried' beans. Mexican Spanish often uses the prefix 're-' to describe something exceptional. 'Rebueno' means 'really, really good'. 'Refrito' means–you guessed it–well-fried.

Melt about a tablespoon of manteca (lard) in an 8" frying pan. Split the chiles from the tip almost to the stem end. Fry the chiles until they are blistered and dark brown, almost blackened. To prevent a million splatters, allow to cool a bit before you add the beans to the pan.

Frijoles Refritos Estilo Mexico Cooks! (Refried Beans, Mexico Cooks! Style)

Serves six as a side dish

3 cups recently-cooked frijoles peruanos

1 or 2 chiles serrano, depending on your heat tolerance

1 or 2 Tbsp lard or vegetable oil—preferably lard and definitely NOT olive oil

Bean cooking liquid

Sea salt to taste

Melt the lard in an 8-inch skillet. Split the chile(s) from the tip almost to the stem end and add to the melted lard. Sauté over a medium flame until the chile is dark brown, almost black.

Lower the flame and add the beans and a little bean liquid. When the beans begin to simmer, mash them and the chile with a potato or bean masher until they are smooth. Add more liquid if necessary to give the beans the consistency you prefer. Add sea salt to taste and stir well.

Leave the melted lard and the chiles in the frying pan and add the beans and some pot liquor. Bring to a simmer over low heat. When the beans are hot, start mashing them with a potato or bean masher. Mash the chiles, too.

These beans are about half mashed.

Mexico Cooks! prefers that frijoles refritos have a little texture. These are just right for us, but you might prefer yours perfectly smooth. If you like them smoother, keep mashing! Either way, the beans should be thickly liquid. If the consistency is too thick, add more pot liquor. If the beans are too thin, add a few more whole beans to mash.

For a wonderful breakfast or supper treat, try making molletes estilo Mexico Cooks!. This is real Mexican home cooking; Mexico Cooks! has never seen this style molletes served in a restaurant. A wonderful Michoacán cook taught me how to prepare this easy meal.

Start with fresh pan bolillo (individual-size loaf of dense white bread), split in half lengthwise. Butter the cut bolillo halves and grill them on a comal (griddle) or hot skillet till they're golden brown. If you aren't able to buy bolillos where you live, use a dense French-style bread instead.

Spread each half bolillo with a thick coat–two tablespoons or more–of frijoles refritos.

Top the beans with a freshly fried egg and your favorite bottled or home-made salsa.

Salsa cruda (also known as pico de gallo) is the home-made salsa that I prefer with molletes. Use finely diced perfectly ripe tomatoes, just a bit of minced white onion, as much minced chile serrano as you prefer, a lot of coarsely chopped cilantro, and salt to taste: voilà! Photo courtesy A Bit of Saffron.

Breakfast, estilo Mexico Cooks!, will keep you going strong till time for comida. You're going to love these beans!

¡Provecho!

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.