In 2016, my dear friend and colleague Maestro Rafael Mier were invited to give conferences in the Mexican state of Puebla. After our conferences, we visited the Biosphere Tehuacán-Cuicatlán, important to the world for numerous reasons. Mexico Cooks! wrote then about the discovery of corn, the reason most important to Mstro. Rafael and to me–a reason important to you, as well.

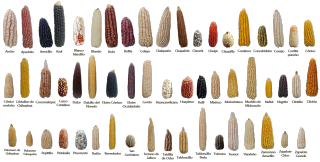

At first glance, these appear to be flowers–but look closely: they're actually cross-sections of different varieties, sizes and colors of maíces nativos (native corn), grown continuously in Mexico for many thousands of years, right up to the present time. They're so beautiful–and delicious! Photo courtesy Tortilla de Maíz Mexicana.

A few weeks ago, CONACULTA (Mexico's ministry of culture) invited Maestro Rafael Mier and Mexico Cooks! to speak about the preservation of traditional tortillas and about the milpa (millennia-old sustainable agricultural method still used in Mexico) at the Second Annual Festival Universo de la Milpa, held this year in Santa María Coapan, Puebla. Santa María Coapan, a part of the municipality of Tehuacán, is at the epicenter of the documented-to-date 11,000 year history of corn.

Left to right in the photo: Maestra Teresa de la Luz Hilario, Regidora de Educación y Cultura de Santa María Coapan; Maestro Rafael Mier of Tortilla de Maíz Mexicana; Mexico Cooks!; (speaking) the humanitarian and life-long human rights abogada del pueblo (advocate for the people) Concepción Hernández Méndez; and at far right, Lic. Roberto G. Quintero Nava, Director General de Culturas Populares of Puebla, CONACULTA. It was an honor to be part of this event and to meet its outstanding participants in this center of Mexican corn production. Photo courtesy Rafael Mier.

In tiny Coxcatlán, Puebla (just down the highway on the road south out of Tehuacán), a main attraction is the monument to corn. The legend at the base of the recently refurbished monument reads, "Coxcatlán, Cuna del Maíz (Cradle of Corn)". All photos copyright Mexico Cooks! unless otherwise noted.

From the small town of Coxcatlán, our driver took us about five kilometers further, south toward the Oaxaca border; there's a turnoff onto a dirt road at the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Biosphere Reserve. The September 24, 2016 Mexico Cooks! article offers some fascinating general information about the biosphere.

If you didn't know to turn onto that poorly marked, narrow, and winding dirt road, you'd just keep whizzing along the highway, saying, "Nothing to see here, just a lot of big cactus and scrub trees. The Oaxaca border is only 30 kilometers away, let's hurry so we get there before dark." But this humble dirt road twists through a portion of an internationally important site marking the origin and development of agriculture in Mesoamerica and the world. Archeological research here has provided key information regarding the domestication of various species such as corn (Zea mays sp.), chile (Capsicum annuum), amaranth (Amaranthus sp.), avocado (Persea americana), squash (Cucurbita sp.), bean (Phaseolus sp.), and numerous other plants that are with us still in the modern era. This biosphere is home to just under 3000 kinds of native flora plus the largest collection of columnar cacti in the world. In addition, the biosphere contains approximately 600 species of vertebrate animals. Let's not hurry–let's spend some time here.

Archeologist Richard S. MacNeish (April 29, 1918-January 16, 2001). In 1965, Dr. MacNeish and a group of his colleagues first uncovered the agricultural treasures in the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán biosphere. Their excavation resulted in some of the most significant agricultural finds in the world. A statue in his memory is prominent today in Tehuacán. Dr. MacNeish, one of the most outstanding archaeologists of the Americas, developed innovative field methods that allowed him and his teams of co-archaeologists, anthropologists, sociologists, agronomists, and others to use science rather than educated guesswork to locate potentially important sites for excavation. Other than his discoveries in this biosphere, which are crucial to our understanding of Mesoamerican agriculture and settlement, his greatest legacy is probably his influence on and encouragement of students, other archaeologists, and the multitude of scientific professionals with whom he worked. Photo of Dr. MacNeish courtesy LibraryThing.

My good friend and colleague Rafael Mier, founder of Tortilla de Maíz Mexicana (by all means join the Facebook group), had talked a good while with me about his desire to visit the site where, over 50 years ago, Dr. MacNeish documented the remains of ancient corn. The more we talked about going to the cave, the more my heart raced: We were going to visit one of the places in Mexico where corn was born. Where corn was born. I felt that the trip would be much more than a Sunday drive in the country: it felt like a pilgrimage, to the most basic food destination in Mexico. To the origin of everything.

The extremely ancient peoples of what is now Mexico domesticated a native wild-growing plant called teocintle, which over the course of many years became what we know today as corn. Teocintle–the photo above is a seed head of the plant, harvested in 2015 in the State of Mexico and framed in sterling silver–is a grass similar to rice in that the grains grow and mature as a cluster of individuals, on a stalk. A mazorca (seed head) of teocintle has no center structure; no cob, if you will. One of the primary features that distinguishes corn from teocintle is the cob. Scientists tracked the domestication of teocintle from the wild grain to its semi-domesticated state, and from semi-domestication to the incredible variety of native Mexican corns that we know today. The actual teocintle seed head in the photo measures approximately three inches long. What you see in my hand is the million-times-over great-grandfather, the ancient ancestor of corn.

The mouth of la Cuna del Maíz Mexicano (the cradle of Mexican corn). I grew up in the southern United States, where I knew a few caves. I had expected to see a cave along the lines of Wyandotte Caves in Indiana, or Mammoth Cave in Kentucky: huge, multi-room caverns in which a person can walk along seeing rivers, stalagmites, stalactites, and other underground cave formations. Not here; this cave is simply what you see in the photograph, a sheltering karst-formation in the limestone, a pre-historic bubble. Standing in this spot gave me chills, and simply thinking about it while looking at the photograph now makes a shiver run up my spine. Out here in the vastness of this ancient natural world, in some ways so similar to the primitive world into which corn was born, one forgets about the crowded city, one forgets about modern problems, and one returns both mentally and spiritually to another time and to a connection with those Stone Age people who gave us the gift of corn, the true staff of life in much of today's world.

This shelter, according to years-long archeological research by Dr. MacNeish and others, was used as a camp, as a shelter during the rainy season for as many as 25 to 30 people, and as a post-harvest storage place for corn and other native vegetables (corn, beans, chiles, etc). Families, bands of families, and tribes living in or traveling through the Coxcatlán area used this type shelter for 10,000 years or more, primarily during the time in Mesoamerica that is analogous to the Archaic archeological period: approximately 5000 to 3400 BCE. Dr. MacNeish's extensive research showed more than 42 separate occupations, 28 habitation zones, and seven cultural phases in this cave.

At the Museo del Maíz (Corn Museum) in Tehuacán, there is a small display of the original dehydrated corn cobs as well as some utensils found in the cave in the biosphere. This tiny cob measures less than one inch long.

![Cueva Museo Olotes Fo?siles Rafa Cueva Museo Olotes Fo?siles Rafa]()

These dehydrated cobs, also found in the cave, are quite a bit larger and probably somewhat younger than the tiny one in the photo above. They measure between 2 and 3 inches long. Some ancient fingers plucked this corn from its stalk, some long-ago woman–she must have been a woman–removed the kernels from the cobs and prepared food. How similar the growing methods, how similar what they ate, those people who created corn from a wild plant. Corn, beans, chiles, squash, amaranth, avocado: all served up in some way for millennia-past meals, and all available in Mexico's markets today. What foods do you eat that nourished your Stone Age forebears? How precious it is to know and taste the flavors of 7 to 10 thousand years worth of comidas (Mexico's main meal of the day)!

In addition to the important finding of dehydrated corn cob specimens (nearly 25,000 samples) and other kinds of vegetables in the substrata of the Tehuacán cave, Dr. MacNeish and subsequent archeologists found a large number of ancient tools such as chipped-flint darts used for hunting, grinding stones, and coas (pointed sticks used for planting). The investigators also found approximately 100 samples of human feces, which were examined to document the human diet of those long-ago days. Thanks to carbon dating, a method of determining the age of organic objects which was developed in the 1940s, scientists were and continue to be able to assign dates to ancient artifacts.

Part of a mural found in ruins dating to 650-900 AD in Cacaxtla, Tlaxcala. Click on the photograph to enlarge it; you'll see that what initially appear to be ears of corn are in fact a part of Mexico's creation myth: humankind is born of corn, and corn is born of humankind. Corn, which humankind created in the domestication process, cannot in fact exist without a human helping hand to husk it, take the dried kernels from the cob, and plant those kernels for subsequent harvest. Above even wheat and rice, corn is the single-most planted grain in the world; there are countries and regions where humans could not exist without corn.

This tiny mazorca (dried ear of corn) is maíz palomero: (popcorn, scientific name Zaya mays everta), native to Mexico, the only kind of corn in the world that pops. Maíz palomero is believed by many scientists to have been the first corn. Today, this original corn is tragically all but extinct in Mexico. My colleague Maestro Rafael Mier, who lives in Mexico City, wanted to plant it; he contacted a number of possible sources without locating any seed at all. He ultimately called a seed bank in a nearby Mexican state to see if they had some. They did, and they took seeds out of their freezer bank so that he could sow them on his property. His goal is to begin the reversal of the extinction of this original Mexican corn. This wee ear of popcorn, the standard size for this variety, is just about four inches long. Look how beautiful it is, with its crystalline white and golden triangular kernels.

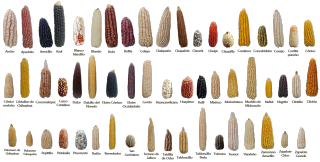

Mexico still grows and cooks with 59 different varieties of native corns, corns that are essential to the regions in which they grow. A type of native corn that grows well in the state of Tamaulipas, for example, will probably not produce as well in Oaxaca. Nor will a native corn that is easily produced in the west-central state of Guerrero grow well in the north-eastern Mexico state of Coahuila. Climates differ, altitudes differ, soils differ: all impact Mexico's native corns. If you click on the poster to enlarge it, you'll see how very, very different Mexico's 59 corn varieties are from one another. Click on any photo to enlarge it for a better view. Photo courtesy CIMMYT.

These multi-colored mazorcas are native to the Mexican state of Tlaxcala, the smallest state in the República.

These elotes (ears of freshly harvested young corn) are native to the state of Michoacán.

These large fresh ears are elotes of maíz cacahuatzintle, from the State of México, for sale earlier this summer at Mexico City's Mercado de Jamaica. This type corn is processed naturally so it can be used to make pozole, a pork (or chicken) soup with deliciously spicy broth.

A bowl of pozole on a chilly night at the Mercado Medellín, Mexico City, a few Decembers ago.

And finally, these mazorcas are native to the far-southern state of Chiapas.

Mexico knows itself as 'the people of the corn'. Mexico knows that sin maíz no hay país–without corn, there is no country. Right now, Mexico is at a crisis point, the point of preserving its heritage of corn–or allowing that heritage to be lost to the transnational producers of uniform, high-yielding, genetically modified corn that is not Mexico's corn. The Chinese characters in the photo mean crisis, defined as both danger and opportunity. Which word will Mexico choose to safeguard its heritage and frame its future? I take my stand on the side of the 11,000 year history that defines us.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.