I first ate a meal in the beautiful central patio at Fonda Marceva in 2008–12 years ago, shortly after the restaurant opened. There has never been a time when I have not eaten there, dreamed of eating there, or wished I were eating one of their delicious house-prepared dishes from the Tierra Caliente, the southern hotlands of Michoacán. A fonda is normally a small, family-run restaurant featuring home-style food. Fonda Marceva fits that description–except it's quite large and decorated to a fare-thee-well with the owners' collection of Mexican artisan work.

Over the years, the owners have become very good friends: the founder, don Margarito and his wonderful wife; their incredible daughter Leonorilda Cega and her brother Héctor Celis, who manage each of Marceva's two locations, as well as other family members. It's always a privilege and a delight to share a table with friends at Fonda Marceva, and there is very little on the menu that doesn't call my name. My personal favorites are the aporreado, the chambarete, and the caldo de habas–oh, and the frito the uchepos, the toqueras, the frijoles–well, you can find your own favorites.

Right now, most restaurants in the world are under tremendous financial pressure to survive, due to Covid-19. Fonda Marceva is no different from the rest–except for its quality of food, its old-fashioned attentive service, and its moderate prices. If you live in Morelia, or if you visit here regularly, be assured that the restaurant maintains all recommended health guidelines for protecting its customers: masks and/or face shields for the wait staff, extreme attention to cleanliness of all furniture, dishes, and anything else a customer might touch, and available antibacterial gel for hands of staff and customers alike.

This past week, I was fortunate to have breakfast with a group of friends at Fonda Marceva. Do plan a visit yourselves. It's crucially important to support our local businesses, keep our Michoacán traditions alive, and spend some time–at a healthy distance–with our friends.

Just two or three blocks south of the Cathedral in Morelia, at Calle Abasolo 455, this inconspicuous doorway is the gateway to the best regional food in town. Stepping into the restaurant is like stepping back in time, to a gentler era, to a delightful waitstaff, and to home-style food created to please your palate.

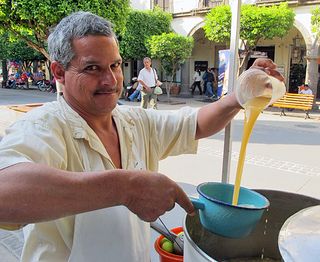

Entradas (appetizers) include frijolitos (beans), queso fresco del rancho (freshly-made farm cheese), Mexican table cream brought from the ranch, salsa, and hot tortillas. The red drink is a conga, a mix of freshly-squeezed fruit juices and grenadine.

Salsa, frijoles, and a fresh, hot, hand-made tortilla…heaven on your plate.

Conjunto "Vargas" plays and sings terrific música abajeña (music from the lowlands) as they stroll around the restaurant.

Even the photo of this carne asada (grilled steak) plate still makes my mouth water. Two huge pieces of grilled steak, grilled onions, rice, sliced ripe tomatoes, avocados, and crunchy cucumbers are accompanied by fresh limones (Key limes) to squeeze over everything.

A common home-style dish, aporreado, is hard to find on a restaurant menu. The dish combines cecina (dried beef) and scrambled egg with a spicy caldillo de jitomate (thin broth). It's so good; during the eight years that I lived in Mexico City, I had to go to Fonda Marceva to eat it every time I came to Morelia. Once I even took a liter of aporreado home with me, on the bus!

The Sunday buffet is a super way to enjoy a leisurely and extensive breakfast with family or friends. You'll find everything on the buffet from fresh juice and seasonal fruits with (or without) yoghurt to house-made toqueras, six or eight delicious main dishes, and everything else you could possibly want to eat. I can't go this Sunday, but who wants to go in July? Name the date and time and I'll meet you there. Photo courtesy Fonda Marceva.

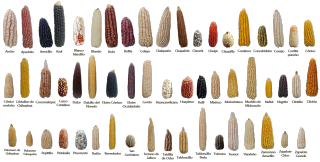

Toqueras! Mexico Cooks! has eaten in hundreds of Mexico's homes and restaurants and has never before seen these on a menu. Similar to corn gorditas (thick tortillas), they are unbelievably delicious. You can try making them at home if you have access to fresh field corn.

TOQUERAS

Ingredients

5 ears fresh white field or dent corn (don't try to use sweet corn, the recipe won't work)

1 egg yolk

1/2 small white onion, sliced thin

1 tsp baking soda

1/2 tsp salt

pinch of white sugar

1/3 cup melted butter

lard

Equipment

Blender

Sharp knife

Bowl

Spoon

Griddle

Procedure

Cut the corn kernels off the cob and grind in a blender together with the egg yolk, sliced onion, baking soda, sugar, salt, and butter.

Heat the griddle and grease lightly with lard. Pat the corn dough into rounds approximately 4" in diameter and 1/4" thick. Grill until golden brown on one side; flip and grill until golden brown on the other side. Be sure to keep the grill well-greased with lard or the dough will stick.

Serve with pure Mexican crema (or substitute creme fraiche) and a salsa de mesa muy picante (a really hot table sauce).

Provecho!

Fonda Marceva

Calle Abasolo 455

Centro Histórico

Morelia, Michoacán

Reservations: 443-312-1666

Hours:

9:00 AM until 6:00 PM Monday through Sunday

Breakfast buffet on Sunday until 3:00PM

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours