Celebrating the first of June–with a taco made with a real tortilla: freshly nixtamalize-d native Mexican dried corn ground into damp masa (corn dough), patted or pressed out, and cooked on a comal (griddle) at Tortillería Ichuskata, in Morelia, Michoacán. I had been to a food event in the city and brought a half-kilo home with me–they're so delicious, it didn't even matter what was in the taco–the tortilla was just perfect! If you've never eaten a real tortilla–not from a plastic package, not even from the general run of tortillerías–you haven't enjoyed one of life's greatest pleasures. Anything else just isn't worth it.

In Mexico, our presidential election is held every six years on July 1. Just after casting the ballot, your thumb is stamped to show that you voted. Every election since 2006, I've voted for the candidate who won the presidency this year: Andrés Manuel López Obrador. I'm so thrilled and proud that he won! That's my thumb, hiding my grin!

Pesca del día–catch of the day on July 28–at Restaurante Pasillo de Humo, Mexico City. The robalo (Centropomus mexicanus), cooked perfectly and with a crisp, delicious skin, is served over a heap of freshly cooked vegetables. In this case, there were fresh fava beans, fresh peas, fresh corn, and the tiniest whole fresh carrots. Pasillo de Humo is consistently marvelous, and this fish preparation is no exception.

Mexico Cooks! spent the first two weeks of August leading two back-to-back tours in Oaxaca. One of the must-do markets in Oaxaca is in Tlacolula, south of Oaxaca City, where my early-August group exclaimed over everything they saw, including the gorgeous rambutan displays. The rambutan, an Asian fruit grown extensively in Mexico's southernmost state of Chiapas, is similar to the lychee, but as you can, see the red skin has long red feelers–well, maybe not quite feelers, but don't they look like feelers? Inside the flesh is white, like the lychee, with a similar texture, flavor and a similar stone.

You can find just about anything you need at Mexico's markets, including household goods, fruits and vegetables, and brassieres of uplifting colors.

In Tlacolula this past August, we also saw wheelbarrows full of beautifully ripe, Oaxaca-grown melón (cantaloupe). The deep orange flesh is perfect, slightly tender, running with sweet juices, and ready for your table at any meal of the day. Mexican home and restaurant cooks also make an agua fresca (fresh fruit water) with melón; it's one of my favorites.

___________________________________________

Photo courtesy Mi Mero Mole.

Agua Fresca de Melón

Fresh Cantaloupe Water

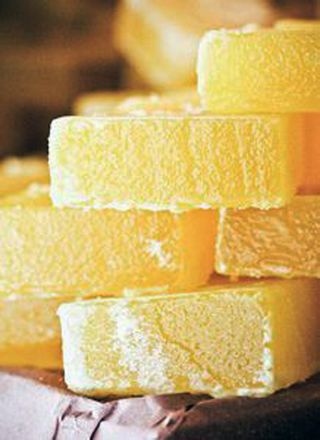

1/2 ripe cantaloupe, peeled and with seeds removed

1/2 cup sugar

6 cups water

Cut the peeled cantaloupe into chunks.

Put the chunks of fruit, the sugar, and 2 cups of water in a blender. Blend for 30 seconds. Add another cup of water and blend for an additional 30 seconds.

Pour the blended mixture into a pitcher and add the remaining 3 cups of water. Stir until completely mixed.

The cantaloupe water should be chilled before serving. Just prior to serving, stir the pitcherful again, with a large spoon.

**Note: if you prefer this agua fresca a bit sweeter, add more sugar to taste. You can also replace all of the sugar with an equal amount of Splenda granulated no-calorie sweetener.

Serves 6

_____________________________________________

My second August tour group was invited to a private traditional cooks' event, organized just for us by Srta. Petra Cruz González, the president of the Unión de Palmeadoras (Tortilla Makers' Union) in Tlaxiaco, Oaxaca. Tlaxiaco is located high in the Mixteca Alta about 2.5 hours north of the city of Oaxaca. Several of the union members demonstrated how Oaxaca-style tortillas are made, and then invited us to partake of a comida (main meal of the day) that the women had prepared for us. In the photograph, you see a freshly made blue corn tortilla filled with requesón (a spreadable white cheese similar to ricotta), delicious frijoles de la olla (whole beans just out of the cooking pot), a bit of chicharrón (fried pork skin, the light brown square at the top left), and spicy salsa, made in a molcajete (volcanic stone grinding bowl).

Was it good? Yes it was! The home made food, cooked over wood fires, was simple, heart-warming, and exactly what we needed. We ate and drank and chatted with the cocineras traditionales (traditional cooks), enjoying their company as much as we enjoyed their food.

After the tours in Oaxaca, I came home to Mexico City to this new member of the family. When I picked her up mid-August from her rescuer, Pili was a tiny eight weeks old. Today, she's six months old and is fully integrated into the group the boss of the bunch–and certainly MY boss. Neither the three other cats in my household nor I stand a chance against Her Highness.

Above, a quesadilla sin queso (quesadilla without cheese). "With or without cheese" is a perpetual discussion among people who live in Mexico City. One faction says, "A quesadilla doesn't need cheese." The other side says, "It has to have cheese, why else is it called quesadilla?" The one in the photograph, prepared with chicharrón prensado (the pressed-together ends and various leavings in a pot used to fry pig skins) at a Sunday flea market just north of Mexico City's Centro Histórico, has no cheese. Regardless of which side of the cheese/no cheese argument you're on, you'd love to have this for breakfast.

In central highlands of Mexico, September is the middle of the rainy season, when nearly daily rains wet our mountainous oak and pine forests. Beneath the trees, many varieties of wild mushrooms spring up each night, to be harvested in the morning and brought to market. The bounty of the nightly harvests grace both home and restaurant tables; Mexico Cooks! buys setas and oyster mushrooms like those in the photograph, as well as many other wild varieties. Photo courtesy Rafael Mier.

Meet Sra. Georgina Gómez Mejía, who sells wild mushrooms during their season at the Mercado de Jamaica in Mexico City. Depending on what she finds in the forests near her home in the neighboring State of Mexico, she brings lobster mushrooms, oyster mushrooms, hens and chickens mushrooms, chanterelles, and morels, the king of wild mushrooms. In mid-September, I bought two kilos (about 4.5 pounds) of enormous wild mushrooms from her and made enough mushroom soup to eat, to freeze, and to give to friends.

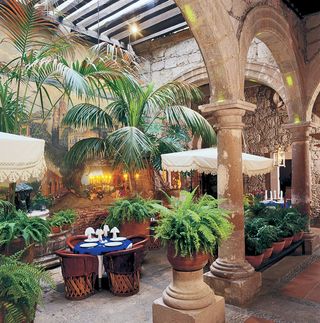

Here, the October setting for a private dinner for 100 people in Morelia, to which I was invited by city government. The dinner, prepared and mounted by Restaurante La Conspiración de 1809, took place in the Palacio Municipal de Morelia in the Centro Histórico of that city. The building dates to the late 18th century and was the perfect location for the event, which included not only a multi-course meal, wines and other drinks, but also a play, presented on the stairway in the photo and throughout the entire room. It was an evening of tremendous excitement and delight, in every respect.

Mid-Fall, we begin to see romeritos (in English, the awful name seepweed) in our Mexico City markets. Romeritos are a leafy herb that looks somewhat like a softer, non-woody version of rosemary. The long, skinny leaves look similar to the thin needles of the rosemary plant, growing like feathers along a central stem. Unlike the stiff stems and needles of rosemary, romeritos are soft and floppy, more like a succulent, with a slightly acidic taste. Generally eaten at Christmastime, they are cooked in mole and accompanied by patties of dried shrimp.

In November I was surprised to see these enormous yaca (jackfruit) in a Mexico City supermarket. The biggest ones in the photo are about 24" long! Usually the fruit is opened and sold in segments, by weight. Inside, the orange-colored flesh is encapsulated into small pieces. It grows on Mexico's coasts. To the right of the yacas is a bin of tunas–in English, they're known as prickly pear cactus fruit.

Making longaniza, a spicy sausage very similar to chorizo, at the Mercado de Jamaica. November 2018.

The first week of December, a young friend in Baltimore and I had a ball with a long-distance bakeoff, each of us preparing the same recipe for blueberry coffee cake, at the same time, but she in Baltimore and I in Mexico City. It was enormously fun to do this! If you have teenage grandchildren in a city far from where you live, I think this would be wonderful to give you something to do together–choose a simple recipe that you would both enjoy, send one another photos of the process as you're doing it, and take the first bite at the same time. I know my friend Bea and I felt that we were doing something together despite the physical distance between us.

Later in December, a visiting friend from Oaxaca and I enjoyed wandering around Mexico City to see some sights:

Sunshine and shadows at the Casa Museo Friday Kahlo, in beautiful Coyoacán.

Stairway at the Palacio de Correos de México (Mexico's main post office), Centro Histórico. The first stone was laid in 1902, the building was finished in 1907, and was almost destroyed in Mexico City's September 1985 earthquake. The building was restored in the 1990s.

Pozole at the Mercado Navideño (Christmas market) at the Mercado Medellín, Colonia Roma.

Finally, an arbolito de navidad (Christmas tree) at the Mercado de Jamaica. Decorated with tiny lights and ornaments, the owner of this market booth also hung the tree with the product he makes and sells: crisp corn t

ostadas! Adorable!

Mexico Cooks! hopes that 2019 brings all of you the best of everything throughout the year. Come along with us as we see more of Mexico, her cultures and her cuisines–see you next Saturday!

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.