Originally published on December 8, 2007, this story of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe (Our Lady of Guadalupe) has been one of the most-read articles published since the inception of Mexico Cooks!. Her feast day in 2022 is Monday, December 12.

The new Basílica de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe (Our Lady of Guadalupe), built between 1974 and 1976, is the second most visited religious sites in the world. The first is the Vatican. Photo courtesy El Viator.

My head was whirling with excitement at 7 AM last New Year's Day. I was in a taxi going to the Guadalajara airport, ready to catch a flight to Mexico City. Although I had lived in the Distrito Federal (Mexico's capital city) in the early 1980s, it had been too many years since I'd been back. Now I was going to spend five days with my friends Clara and Fabiola in their apartment in the southern section of the city. We had drafted a long agenda of things we wanted to do and places we wanted to visit together.

The old Basílica was finished in 1709. It's slowly sinking into the ground. You can easily see that it is not level.

First on our list, first on every list of everyone going to Mexico City, is the Basílica of Our Lady of Guadalupe, the heart of the heart of Mexico. When I chatted with my neighbors in Guadalajara about my upcoming trip, every single person's first question was, "Van a la Villa?" ("Are you going to the Basílica)"

To each inquirer I grinned and answered, "Of course! Vamos primero a echarle una visita a la virgencita." (The first thing we'll do is pay a visit to the little virgin!)

The interior of the new Basílica holds 50,000 people.

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe is Mexico's patron saint, and her image adorns churches and altars, house fronts and interiors, taxis and buses, bull rings and gambling dens, restaurants and houses of ill repute. The shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe, La Villa, is a place of extraordinary vitality and celebration. On major festival days such as the anniversary of the apparition on December 12th, 1531, the atmosphere of devotion created by the literally millions of pilgrims is truly electrifying.

Click here to see: List of Pilgrimages, December 2006. There are often 30 Masses offered during the course of a single day, each Mass for a different group of pilgrims as well as open to the general public.

The enormous Basílica of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe in Mexico City, located, on the hill of Tepeyac, was a place of great sanctity long before the arrival of Christianity in the New World. In pre-Hispanic times, Tepeyac had been crowned with a temple dedicated to an earth and fertility goddess called Tonantzin, the Mother of the Gods. Tonantzin was a virgin goddess associated with the moon, like Our Lady of Guadalupe who usurped her shrine.

The Tepeyac hill and shrine were important pilgrimage places for the nearby Mexica (later Aztec) capital city of Tenochtitlán. Following the conquest of Tenochtitlán by Hernan Cortez in 1521, the shrine was demolished, and the native people were forbidden to continue their pilgrimages to the sacred hill. In Christian Europe, 'pagan' practices had been considered to be devil worship for more than a thousand years.

Some of you may not know the story of Our Lady of Guadalupe. For all of us of whatever faith who love Mexico, it's important to understand the origins of the one who is the Queen, the Mother, the beloved guardian of the Republic and of all the Americas. She is the key to understanding the character of Mexico. Without knowing her story, it's simply not possible to know Mexico. Indulge me while I tell you.

On Saturday, December 9, 1531, a baptized Mexica indigenous man named Juan Diego set out for church in a nearby town. Passing the pagan sacred hill of Tepeyac, he heard a voice calling to him. Climbing the hill, he saw on the summit a young woman who seemed to be no more than fourteen years old, standing in a golden mist.

Revealing herself as the "ever-virgin Holy Mary, Mother of God" (so the Christian telling of the story goes), she told Juan Diego–in his indigenous language–not to be afraid. Her words? "Am I not here, I who am your mother?" She asked where he was going. He told her he was going to Tenochtitlán to buy medicine for his sick uncle. She instructed him to go instead to the local bishop and tell him that she wished a church for her son to be built on the hill. She herself promised to take care of his uncle. Juan did as he was instructed, but the bishop's staff did not believe him and told him to scram.

On his way home, Juan climbed the sacred hill and again saw the apparition, who told him to return to the bishop the next day. This time the bishop's staff listened more attentively to Juan's message from Mary. They were still skeptical, however, and so asked him to come back, bringing a sign from her.

On December 12, Juan went again to Tepeyac and, when he again met Mary, she told him to climb the hill and pick the roses that were growing there. Juan climbed the hill with misgivings. It was the dead of winter, and flowers could not possibly be growing on the cold and frosty mountain. At the summit, Juan found a profusion of roses, an armful of which he gathered and wrapped in his tilma (a garment similar to a long apron). Arranging the roses, Mary instructed Juan to take the tilma-encased bundle to the bishop, for this would be her sign.

When the bishop unrolled the tilma, he was astounded by the presence of the flowers. They were roses that grew only in Spain, roses he recognized immediately. But more truly miraculous was the image that had mysteriously appeared on Juan Diego's tilma. The image showed the young woman, her head lowered demurely. Wearing a crown and flowing gown, surrounded by a golden resplandor, she stood upon a half moon sustained by a cherub. The bishop was convinced that Mary had indeed appeared to Juan Diego and soon thereafter the bishop began construction of the original church devoted to her honor.

News of the miraculous apparition of the Virgin's image on a peasant's tilma spread rapidly throughout Mexico. Indigenous people by the thousands came from hundreds of miles away to see the image, now hanging above the altar in the new church. They learned that the mother of the Christian God had appeared to one of their own kind and spoken to him in his native language. The miraculous image was to have a powerful influence on the advancement of the Church's mission in Mexico. In only seven years, from 1532 to 1538, more than eight million indigenous people were converted to Christianity.

The shrine, rebuilt several times over the centuries, is today a great Basílica with a capacity for 50,000 pilgrims.

Juan Diego's tilma is preserved behind bulletproof glass and hangs twenty-five feet above the main altar in the basilica. For nearly 500 years, the colors of the image have remained as bright as if they were painted yesterday, despite being exposed for more than 100 years following the apparition to humidity, smoke from church candles, and airborne salts.

The coarsely-woven cactus cloth of the tilma, a cloth considered to have a life expectancy of about 40 years, still shows no evidence of decay. The 46 stars on her gown coincide with the position of the constellations in the heavens at the time of the winter solstice in 1531. Scientists have investigated the nature of the image and have been left with nothing more than evidence of the mystery of a miracle. The dyes forming her portrait have no base in the elements known to science.

The origin of the name Guadalupe has always been a matter of controversy. It is believed that the name came about because of the translation from Náhuatl to Spanish of the words used by the Virgin during the apparition. It is believed that she used the Náhuatl word coatlaxopeuh which is pronounced "koh-ah-tlah-SUH-peh" and sounds remarkably like the Spanish word Guadalupe. 'Coa' means serpent, 'tla' can be interpreted as "the", while 'xopeuh' means to crush or stamp out. This version of the origin would indicate that Mary must have called herself "she who crushes the serpent," a Christian New Testament reference as well as a a reference to the Mexica's mythical god, The Plumed Serpent.

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe statues of all sizes are for sale at the Basílica.

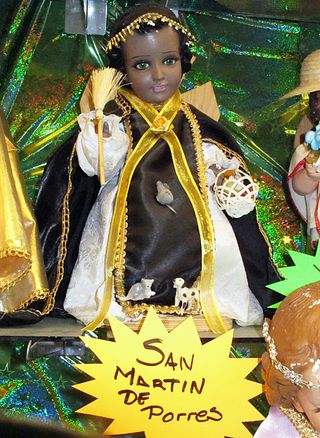

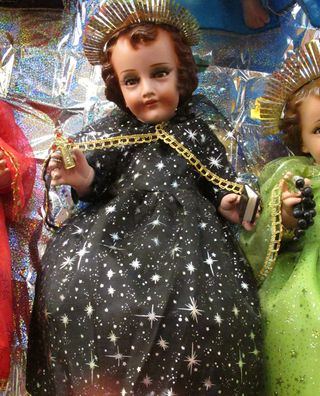

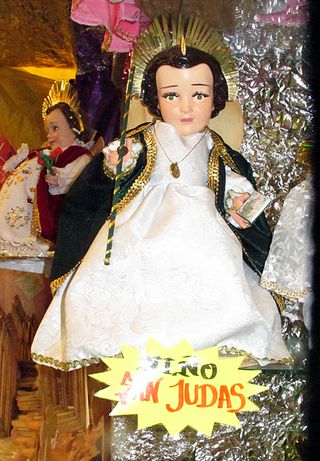

Clara, Fabiola, and I took the Metro and a microbus to La Villa, a journey of about an hour from their apartment in the south to the far northern part of the city. We left the bus at the two-block-long bridge that leads to the Basílica and decided to take a shopping tour before entering the shrine. The street and the bridge are filled chock-a-block with booths selling souvenirs of La Villa. Everything that you can think of (and plenty you would never think of) is available: piles of t-shirts with the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe and that of Juan Diego, CDs of songs devoted to her, bandanna-like scarves with her portrait, eerie green glow-in-the-dark figurines of her, key chains shaped like the Basílica, statues of her in every size and quality, holy water containers that look like her in pink, blue, silver, and pearly white plastic, religious-themed jewelry and rosaries that smell of rose petals, snow globes with tiny statues of La Guadalupana and the kneeling Juan Diego that are dusted with stars when the globes are shaken.

You can have your picture taken as a memento of your visit to the Virgin.

There are booths selling freshly arranged flowers for pilgrims to carry to the shrine. There are booths selling soft drinks, tacos, and candy. Ice cream vendors hawk paletas (popsicles). Hordes of children offer chicles (chewing gum) for sale. We were jostled and pushed as the crowd grew denser near the Basílica.

The virgin's image is everywhere.

Is it tacky? Yes, without a doubt. Is it wonderful? Yes, without a doubt. It's the very juxtaposition of the tourist tchotchkes with the sublime message of the heavens that explain so much about Mexico. I wanted to buy several recuerdos (mementos) for my neighbors in Ajijic and I was hard-pressed to decide what to choose. Some pilgrims buy before going into the Basílica so that their recuerdos can be blessed by a priest, but we decided to wait until after visiting the Virgin to do my shopping.

Pope John Paul II loved Mexico, loved Our Lady of Guadalupe, and visited the country five times during his tenure as pope. Here he celebrates Mass at the new Basílica.

The present church was constructed on the site of the 16th-century Old Basílica, the one that was finished in 1709. When the Old Basílica became dangerous due to the sinking of its foundations, a modern structure called the new Basílica was built nearby. The original image of the Virgin of Guadalupe is now housed above the altar in this new Basílica.

Built between 1974 and 1976, the new Basílica was designed by architect Pedro Ramírez Vásquez. Its seven front doors are an allusion to the seven gates of Celestial Jerusalem referred to by Christ. It has a circular floor plan so that the image of the Virgin can be seen from any point within the building. An empty crucifix symbolizes Christ's resurrection. The choir is located between the altar and the churchgoers to indicate that it, too, is part of the group of the faithful. To the sides are the chapels of the Santísimo Sacramento (the Blessed Sacrament) and of Saint Joseph.

One of the many processions that constantly arrive from cities and towns all over Mexico and the Americas.

We entered the tall iron gates to the Basílica atrium. It was still early enough in the day that the crowds weren't crushing, although people were streaming in. Clara turned to me, asking, "How do you feel, now that you're back here?"

I thought about it for a moment, reflecting on what I was experiencing. "The first time I came here, I didn't believe the story about the Virgin's appearance to Juan Diego. I thought, 'Yeah, right'. But the minute I saw the tilma that day, I knew—I mean I really knew—that it was all true, that she really had come here and that really is her portrait." We were walking closer and closer to the entrance we'd picked to go in and my heart was beating faster. "I feel the same excitement coming here today that I have felt every time since that first time I came, the same sense of awe and wonder." Clara nodded and then lifted her head slightly to indicate that I look at what she was seeing.

Faith.

I watched briefly while a family moved painfully toward its goal. The father, on his knees and carrying the baby, was accompanied by his wife and young son, who walked next to him with his hand on his shoulder. Their older son moved ahead of them on his knees toward an entrance of the Basílica. Their faith was evident in their faces. The purpose of their pilgrimage was not. Had the wife's pregnancy been difficult and was their journey one of gratitude for a safe birth? Had the baby been born ill? Was the father recently given a job to support the family, or did he desperately need one? Whatever the reason for their pilgrimage, the united family was going to see their Mother, either to ask for or to give thanks for her help.

Clara, Fabiola, and I entered the Basílica as one Mass was ending and another was beginning. Pilgrims were pouring in to place baskets of flowers on the rail around the altar. The pews were filled and people were standing 10-deep at the back of the church. There were lines of people waiting to be heard in the many confessionals.

We stood for a bit and listened to what the priest was saying. "La misa de once ya se terminó. Decidimos celebrar otra misa ahora a las doce por tanta gente que ha llegado, por tanta fe que se demuestra" ("The Mass at eleven o'clock is over. We decided to celebrate another Mass now at 12 o'clock because so many people have arrived, because of so much faith being demonstrated.")

Indeed, this day was no special feast day on the Catholic calendar. There was no celebration of a special saint's day. However, many people in Mexico have time off from their work during the Christmas and New Year holidays and make a pilgrimage to visit la Virgencita.

The framed tilma hangs above the main altar in the new Basílica.

Making our way through the crowd, we walked down a ramp into the area below and behind the altar. Three moving sidewalks bore crowds of pilgrims past the gold-framed tilma. Tears flowed down the cheeks of some; others made the sign of the cross as they passed, and one woman held her year-old baby up high toward the Virgin. Most, including the three of us, moved from one of the moving sidewalks to another in order to be able to have a longer visit with the Mother of Mexico.

When I visited several years ago, there were only two moving sidewalks. Behind them was space for the faithful to stand and reflect or pray for a few minutes. Today's crush of visitors has required that the space be devoted to movement rather than reflection and rest.

We walked to the back of the Basílica to look at a large bronze crucifix exhibited in a glass case. The crucifix, approximately 3 feet high, is bent backward in a deep arch and lies across a large cushion. According to the placard and the photos from the era, in 1921 a bouquet of flowers was placed directly on the altar of the Old Basílica beneath the framed tilma. It was later discovered that the floral arrangement was left at the altar by an anarchist who had placed a powerful dynamite bomb among the flowers. When the bomb detonated, the altar crucifix was bent nearly double and large portions of the marble altar were destroyed. Nevertheless, no harm came to the tilma and legend has it that the crucified Son protected his Mother.

After a while, we reluctantly left the Basílica. With a long backward glance at the tilma, Clara, Fabiola, and I stepped out into the brilliantly sunny Mexico City afternoon. The throngs in the Basílica atrium still pressed forward to visit the shrine.

Jackson and Perkins created the Our Lady of Guadalupe hybrid floribunda rose.

We stopped in some of the enclosed shops at sidewalk level and then continued over the bridge through the booths of mementos. After I bought the gifts and the priest near the booths blessed them with holy water, we moved away to hail a taxi. My mind was still in the Basílica, with our Mother.

On Monday, December 12, the tiny and gloriously beautiful Santuario de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe in Morelia, Michoacán, will be in full fiesta. Her feast day falls on December 12 each year. Think about her just for a moment as you go about your day. After all, she's the Queen of Mexico and the Empress of the Americas.

How to get there once you're in Mexico City:

- From the Centro Histórico (Historic Downtown) take Metro Line 3 at Hidalgo and transfer to Line 6 at Deportivo 18 de Marzo. Go to the next station, La Villa Basílica. Then walk north two busy blocks until reaching the square.

- From the Hidalgo Metro station take a microbus to La Villa.

- From Zona Rosa take a pesero (microbus) along Reforma Avenue, north to the stop nearest the Basílica.

- Or take a taxi from your hotel, wherever it is in the city. Tell the driver, "A La Villa, por favor. Vamos a echarle una visita a la Virgencita." ("To the Basílica, please. We're going to make a visit to the little Virgin.")

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.