Remember me as you pass by,

As you are now, so once was I.

As I am now, so you will be,

Prepare for death and follow me.

…from a tombstone

What is death? We know its first symptoms: the heart stops pumping, breath and brain activity stop. We know death's look and feel: a still, cold body from which the spirit has fled. The orphan and widow know death's sorrow, the priest knows the liturgy of the departed and the prayers to assuage the pain of those left to mourn. But in most English-speaking countries, death and the living are not friends. We the living look away from our mortality, we talk of the terminally ill in terms of 'if anything happens', not 'when she dies'. We hang the crepe, we cover the mirrors, we say the beads, and some of us fling ourselves sobbing upon the carefully disguised casket as it is lowered into the Astroturf-lined grave.

Octavio Paz, Mexico City's Nobel Laureate poet and essayist who died in 1998, is famously quoted as saying, "In New York, Paris, and London, the word death is never mentioned, because it burns the lips."

Tzintzuntzan, Michoacán panteón (cemetery), Mexico Cooks! photo. These fellows sing to la Descarnada (the fleshless woman) on November 2, 2009.

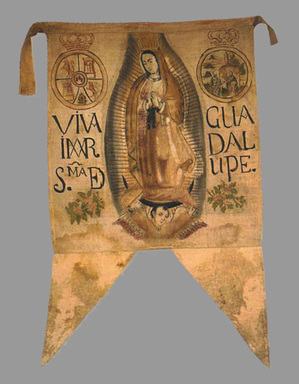

In Mexico, on the contrary, every day is a dance with death. Death is a woman who has a numerous affectionate and humorous nicknames: la Huesuda (the bony woman), la Seria (the serious woman), la Novia Fiel (the faithful bride), la Igualadora (the equalizer), la Dientona (the toothy woman), la Pelona (the bald woman), la Patrona (the boss lady), and a hundred more. She's always here, just around the next corner or maybe right over there, behind that pillar. She waits with patience, until later today or until twelve o'clock next Thursday, or until sometime next year–but when it's your time to go, she's right there, ready to dance away with you at her side.

November 2013 altar to La Santa Muerte (Holy Death), Sta. Ana Chapirito (near Pátzcuaro), Michoacán. Devotees of this deathly apparition say that her cult has existed since before the Spanish arrived in Mexico.

In Mexico, death is also in the midst of life. We see our dead, alive as you and me, each November, when we wait at our cemeteries for those who have gone before to come home, if only for a night. That, in a nutshell, is Noche de Muertos: the Night of the Dead.

In the lower center portion of this photograph, you can see the Quiroga, Michoacán, panteón municipal (town cemetery). Late in the afternoon of November 1, 2013, most townspeople had not yet gone to the cemetery with candles and flowers for their loved ones' graves. Click on any photograph for a larger view.

Over the course of the last 35-plus years, Mexico Cooks! has been to countless Noche de Muertos events, but none as mystical, as magical, or as profoundly spiritual as that of 2013. Invited to accompany a very small group on a private tour in Michoacán, I looked forward to spending three days enjoying the company of old and new friends. I did all that, plus I came away with an extraordinarily privileged view of life and death.

A magnificent Purépecha ofrenda (in this case, a home altar) in the village of Santa Fe de la Laguna, Michoacán. This detailed and lovely ofrenda was created to the memory of the family's maiden aunt, who died at 74. Because she had never married, even at her advanced age she was considered to be an angelito (little angel)–like an innocent child–and her spirit was called back home to the family on November 1, the day of the angelitos. Be sure to click on the photo to see the details of the altar. Fruits, breads, incense, salt, flowers, colors, and candles have particular symbolism and are necessary parts of the ofrenda.

Detail of the ofrenda casera (home altar) shown above. Several local people told Mexico Cooks! that the fruit piled on the altar tasted different from fruit from the same source that had not been used for the ofrenda. "Compramos por ejemplo plátanos y pusimos unos en el altar y otros en la cocina para comer. Ya para el día siguiente, los de la cocina tenían sabor normal, pero los del altar no tenían nada de sabor, no supieron a nada," they said. 'We bought bananas, for example, and we put some on the altar and the rest in the kitchen to eat. The next day, the ones in the kitchen were fine, but the ones from the altar had no taste at all.'

Preparing a family member's ofrenda (altar) in the camposanto in the village of Arócutin, Michoacán. The camposanto–literally, holy ground–is a cemetery contained within the walls of a churchyard. The beautiful beeswax candles used in this area of Michoacán are hand made in Ihuatzio and Santa Fé de la Laguna.

Come with me along the unlit road that skirts the Lago de Pátzcuaro: Lake Pátzcuaro. It's chilly and the roadside weeds are damp with rain that fell earlier in the evening, but for the moment the sky has cleared and is filled with stars. Up the hill on the right and down the slope leading left toward the lake are tiny villages, dark but for the glow of tall candles lit one by one in the cemeteries. Tonight is November 1, the night silent souls wend their way home from Mictlán, the land beyond life.

At the grave: candlelight to illuminate the soul's way, cempazúchitl (deeply orange marigolds) for their distinctive fragrance required to open the path back home, smoldering copal (frankincense) to cleanse the earth and air of any remnants of evil, covered baskets of the deceased's favorite foods. And a low painted chair, where the living can rest through the night.

Watching through the night. This tumba (grave) refused to be photographed head-on. From an oblique angle, the tumba allowed its likeness to be made.

"Oh grave, where is thy victory? Oh death, where is thy sting?"

Noche de Muertos is not a costume party, although you may see it portrayed as such in the press. It is not a drunken brawl, although certain towns appear to welcome that sort of blast-of-banda-music reventón (big blow-out). It is not a tourist event, though respectful strangers are certainly welcomed to these cemeteries. Noche de Muertos is a celebration of the spirit's life over the body's death, a festival of remembrance, a solemn passover. Years ago, in an interview published in the New York Times, Mexico Cooks! said, "Noche de Muertos is about mutual nostalgia. The living remember the dead, and the dead remember the taste of home."

One by one, grave by grave, golden cempazúchitles give shape to rock-bound tombs and long candles give light to what was a dark and lonely place, transforming the cemetery into a glowing garden. How could a soul resist this setting in its honor?

"Our hearts remember…" we promise the dead. Church bells toll slowly throughout the night, calling souls home with their distinctive clamor (death knell). Come…come home. Come…come home.

Waiting. Prayers. No se me olvido de tí, mi viejo amado. (I haven't forgotten you, my dear old man.)

Next year, come with me.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here to see new information: Tours