Everywhere in Mexico, so many events and traditions have been cancelled, postponed, or otherwise affected by the on-going worldwide pandemia. This article, originally published in 2010, is a look back on a Morelia, Michoacán, favorite: the annual month-long festival Caña Fest (the sugar cane festival), that normally begins in mid-November and continues for a month, through December 12, the feast day of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe. Here's how Morelia's festival looked and sounded in 2018:

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=61lVnekLR1I&w=560&h=315]

Originally, the pandemia cancelled the fiesta for 2020. Recently, the government announced that due to public outcry, the festival would indeed take place, but not all in one spot as it is usually scheduled. Some stands will set up in one colonia (neighborhood), others will set up in another colonia, and still others will be relegated to other locations in the city. Will it be the same? No, of course not. Nevertheless, if only ONE case of COVID-19 is prevented, it's worth the change. Let's hope we can be back, business as usual, in 2021. Video courtesy Youtube.

Enjoy these photos and reflections on past Caña Fests!

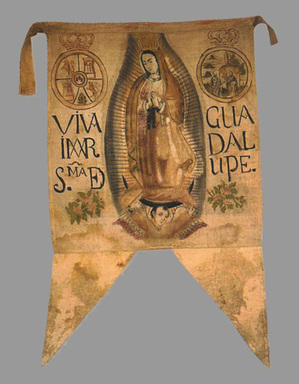

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe (Our Lady of Guadalupe, lovingly nicknamed La Morenita [the little brown woman]), caña (sugar cane), and fresh-roasted cacahuates (peanuts) are an annual combination in Morelia during the weeks from November 19 until the last minutes of the night of December 12, Our Lady of Guadalupe's feast day. The Fiesta de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe is one of the most important religious festivals in all of Mexico, celebrated in every home and every town, in every church and every heart.

Hundreds of tons of freshly in-season caña (sugar cane) are hand-peeled with flashing steel machetes for your eating pleasure. Every year, more than 400 vendors set up food stands, trinket stands, and booths filled with religious articles in Morelia's Jardín Morelos, on Avenida Tata Vasco, and along the Calzada Fray Antonio de San Miguel leading to the Santuario de Guadalupe. Brightly colored children's rides and games illuminate the evening hours in the park; the fragrance of grilling meat competes with the deep smell of roasting peanuts, and the whir of the cotton candy machine pairs up with the rhythmic whack-whack-whack of the caña-cutting knife.

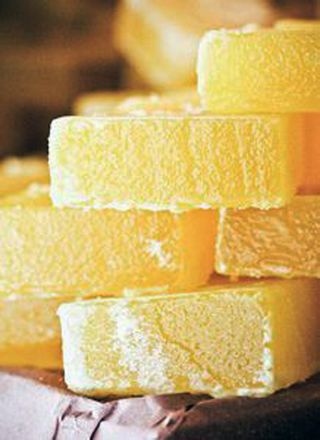

Long sugar canes are fibrous and tough, but hand-chopped with a huge knife into bite-size pieces, caña is easy to chew. Munch a piece until the sweet juice is gone, then discard the mouthful of straw-like fibers that are left. Munch another, it's addictive.

A bed of freshly sliced oranges and a pile of sliced caña con chamoy make a mouth-puckering, refreshing snack. Chamoy is a sour fruit brine that's popular for its flavor combination of vinegar, salt, and sweet fruit.

This roaster toasts about seven kilos (15 pounds) of raw cacahuates (peanuts) at a time. The family that operates this stand had the roaster made from an oil drum, along with a metal box on legs to hold the fuel. One of the family members turns the handle (to the left in the photo) to make sure the peanuts toast evenly, without burning.

The heat for the peanut roaster comes from carbón, Mexico's real-wood charcoal–they're not "briquets" from commercial bags!

Raw habas (fava beans) are toasted by the same method. Roasted habas and cacahuates are sold unsalted.

Here's a juice extractor to make you a glass of super-fresh and sweetly delicious jugo de caña (sugar cane juice). One operator inserts the long sugar canes through the back of the dark metal rollers while another turns the handle on the wheel at the left of the photo.

The juice pours onto the slanted tray, down the spout, and into your waiting plastic cup. A 12-ounce cup of hand-squeezed juice costs ten pesos–less than one United States dollar.

Do you need some real food? Try made-to-order tacos at one of the stands in Plaza Morelos. The bottom pair are bistec (chopped grilled beef), the top two are carne de cerdo al pastor (marinated pork cooked on a vertical spit). A squeeze of lime, a pinch of salt, and a sprinkle of minced cilantro and onion (and of course a spoonful of the hottest salsa you can tolerate) make these tacos delicious.

Maybe pambazos, enchiladas placeras, or taquitos are more to your taste. Everything at this stand is cooked to order on an anafre (brazier). Mexico Cooks! is partial to a good pambazo: it's a sandwich made from an individual-sized loaf of dense white bread, sliced open and dipped in enchilada sauce, filled with picadillo (meat/potato/carrot hash), fried till the bread is just slightly crisp on the outside, and topped with shredded lettuce, diced fresh tomatoes, minced onions, grated Mexican cheese, and a salsa muy picante (really spicy salsa).

The sign asks, "What blankety-blank crisis?" The bags of caña that this dealer offered continued at the 2009 price: 10 pesos. The world economic situation in 2008-2009 deeply affected Mexico, but up until 2020, nothing stopped this party!

Mexico has a real 'thing' for corn dogs. Here in Mexico, they're fair (as in county fair!) food, just like they are in the United States. They make quite a switch from a traditional pambazo, no?

For dessert, local strawberries flash frozen in Zamora, Michoacán, are partially thawed and served with cream. You can see that the cartons are labeled both 'fresas' and 'strawberries' (for the English-language market; strawberry export is an enormous business in Michoacán. Duero is the name of the strawberry packing company, as well as the name of the Michoacán river that runs through Zamora. They're named for the Río Duero roars through western Spain and Portugal.

Take home a bag of candies. Pick the candy you prefer–pea-size chocoretas (mint chocolate balls), crisp-coated lunetas of chocolate, sweet and tart buttons, gummy worms or bears or frogs, and a dozen more choices– and buy as little or as much as you like.

It's traditional for both adults and children to dress in 16th Century indigenous clothing during these December fiestas. This beautiful baby wears painted bigotes (moustache), a tiny poncho, a sombrero de paja (straw hat), and a bright paliacate (handkerchief/scarf), all in honor of San Juan Diego, who first saw and talked with Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe in chilly mid-December of 1531.

I don't know about you, but I'm going to pray for the end of the pandemia and the return of Mexico's traditional festivities.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.