Ash

Wednesday, which marks the beginning of Lent, was on February 13, 2013.

The following article has been very popular as a reference since it was

first published on Mexico Cooks! in 2009. So many people want to know what we eat in Mexico when we're not eating meat! Enjoy…and buen provecho!

Tortitas de papa (potato croquettes, left) and frijoles negros (black beans, right) from the south of Mexico are ideal for a Lenten meal.

Catholic Mexicans observe la Cuaresma (Lent), the 40-day

(excluding Sundays) penitential season that precedes Easter, with

special prayers, vigils, and with extraordinary meatless meals cooked

only on Ash Wednesday and on the Fridays of Lent. Many Mexican

dishes–seafood, vegetable, and egg–are normally prepared without

meat, but some other meatless dishes are particular to Lent. Known as comida cuaresmeña, many of these delicious Lenten foods are little-known outside Mexico and some other parts of Latin America.

Many observant Catholics believe that the personal reflection and

meditation demanded by Lenten practices are more fruitful if the

individual refrains from heavy food indulgence and makes a promise to

abstain from other common habits such as eating candy, smoking

cigarettes, and drinking alcohol. On the other hand, my dear non-Catholic mother (may she rest in peace), once said–at a time of particular late-winter stress–that she was simply going to give up, for Lent.

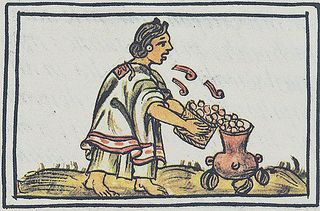

Atole de grano, a Michoacán specialty made of water, fresh, tender corn and licorice-scented anís, is a perfect cena (supper) for Lenten Fridays.

Ash Wednesday, February 13, marked the beginning of Lent in 2013.

Shortly before, certain food specialties began to appear in local

markets. Vendors are currently offering very large dried shrimp for caldos (broths) and tortitas (croquettes), perfect heads of cauliflower for tortitas de coliflor (cauliflower croquettes), seasonal romeritos, and thick, dried slices of bolillo (small loaves of white bread) for capirotada (a kind of bread pudding).

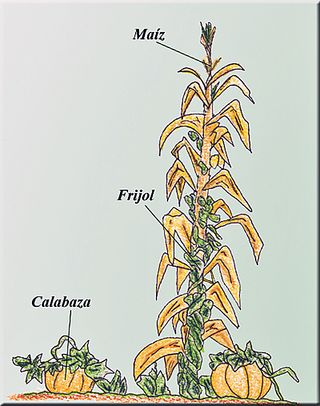

This common Lenten preparation is romeritos en mole. Romeritos,

an acidic green succulent vegetable, is in season at this time of year.

Although it looks a little like rosemary, its taste is relatively sour,

more like verdolagas (purslane).

You'll usually see tortitas de camarón (dried shrimp croquettes) paired for a Friday comida (midday meal) with romeritos en mole, although they are sometimes bathed in a caldillo de jitomate (tomato broth) and served with sliced nopalitos (cactus paddles).

During

Lent, the price of fish and seafood in Mexico goes sky-high

due to the huge seasonal demand for meatless meals. These beautiful huachinangos (red snappers) come from Mexico's Pacific coast.

Tortita de calabacita (little squash fritter) from the sorely missed Restaurante Los Comensales in Morelia, Michoacán. Mexico Cooks! featured the restaurant (the name means 'The Diners') in October 2009. Less than a year after our interview with her, Señora

Catalina Aguirre Camacho, the owner of Los Comensales since 1980,

became too elderly and incapacitated to continue to operate her

wonderful restaurant. This dish is wonderful for a Lenten supper.

Chef Martín Rafael Mendizabal of La Trucha Alegre in Zitacuaro, Michoacán, prepared trucha deshuesada con agridulce de guayaba (boned trout with guava sweet and sour sauce) for the V Encuentro de Cocina Tradicional de Michoacán held in Morelia in December 2008. The dish would be ideal for an elegant Lenten dinner.

Capirotada

(Lenten bread pudding) is almost unknown outside Mexico. Simple to

prepare and absolutely delicious, it's hard to eat it sparingly if

you're trying to keep a Lenten abstinence!

Every family makes a slightly different version of capirotada: a pinch more of this, leave out that, add such-and-such. Mexico Cooks!

prefers to leave out the apricots and add dried pineapple. Make it

once and then tweak the recipe to your preference–but please do stick

with traditional ingredients.

CAPIROTADA

Ingredients

*4 bollilos, in 1" slices (small loaves of dense white bread)

5 stale tortillas

150 grams pecans

50 grams prunes

100 grams raisins

200 grams peanuts

100 grams dried apricots

1 large apple, peeled and sliced thin

100 grams grated Cotija cheese

Peel of one orange, two uses

*3 cones piloncillo (Mexican brown sugar)

Four 3" pieces of Mexican stick cinnamon

2 cloves

Butter

Salt

*If you don't have bolillo, substitute slices of very dense French bread. If you don't have piloncillo, substitute 1/2 cup tightly packed brown sugar.

A large metal or clay baking dish.

Preparation

Preheat the oven to 300°F.

Toast the bread and spread with butter. Slightly overlap the

tortillas in the bottom and along the sides of the baking dish to make a

base for the capirotada. Prepare a thin syrup by boiling the piloncillo in 2 1/2 cups of water with a few shreds of cinnamon sticks, 2/3 of the orange peel, the cloves, and a pinch of salt.

Place the layers of bread rounds in the baking dish so as to allow for their expansion as the capirotada

cooks. Lay down a layer of bread, then a layer of nuts, prunes,

raisins, peanuts and apricots. Continue until all the bread is layered

with the rest. For the final layer, sprinkle the capirotada

with the grated Cotija cheese and the remaining third of the orange peel

(grated). Add the syrup, moistening all the layers little by

little. Reserve a portion of the syrup to add to the capirotada in case it becomes dry during baking.

Bake uncovered until the capirotada is golden brown and the

syrup is absorbed. The bread will expand as it absorbs the syrup.

Remember to add the rest of the syrup if the top of the capirotada looks dry.

Cool the capirotada at room temperature. Do not cover until it is cool; even then, leave the top ajar.

Try very hard not to eat the entire pan of capirotada at one sitting!

A positive thought for the remainder of Lent: give up discouragement, be an optimist.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.