[youtube=://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3vlNbX2ZhbQ&w=420&h=236]

Whether you understand Spanish or not, the video will give you a marvelous feel for the extraordinary XI Encuentro de Cocineras Tradicionales de Michoacán, which took place in Morelia, Michoacán over the weekend of April 3, 4, and 5, 2014. The festival is known more commonly as the Encuentro de Cocina Tradicional de Michoacán.

Since 2007, Mexico Cooks! has been honored to be part of this conference, Mexico's most remarkable festival of traditional cooking. Affectionately known simply as "Las Cocineras" (the cooks), it's part love-fest, part food-fest, part culture-fest, and entirely about traditional indigenous cooking in the west-central Mexican state, Michoacán.

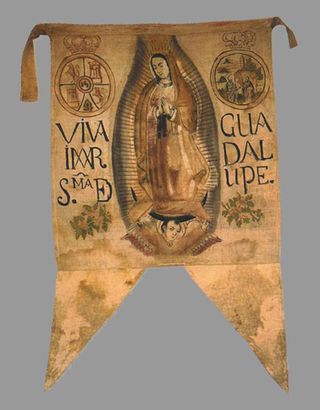

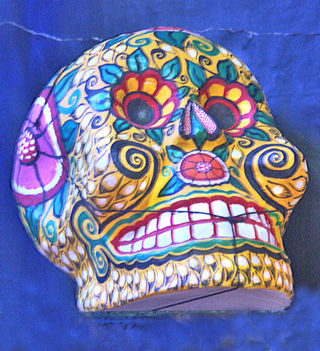

Because of its enormous popularity, the Las Cocineras will have two editions in 2014. The first, celebrated during 2014's Lenten season, took as its theme "Sabores de Cuaresma" (Lenten Flavors). A committee from the artisan town Tzintzuntzan decorated the stage as if it were a traditional Altar de Dolores, an altar dedicated to Our Lady of Sorrows. The second edition this year will take place on October 4, 5, and 6. Click on any image to enlarge it for a better view.

Left to right: Cynthia Martínez Becerril, president of the festival organizing committee; Ana Compeán Reyes Spíndola, representative of the national Secretary of Tourism offices (SECTUR) in Morelia; and Francisco José de la Vega Aragón, Director General de Innovación de Producto Turístico de la SECTUR Federal, immediately following the formal inauguration of the April festivities.

In November 2010, UNESCO awarded its Intangible cultural heritage designation to Mexico's cuisine: Traditional Mexican Cuisine – Ancestral, Ongoing Community Culture, The Michoacán Paradigm. The title is based in large part on this annual event and the manner in which it reflects Michoacán's culinary and cultural heritage. Due to the undisputed and unique importance of this festival to Mexico as a whole, representatives from Mexico's state and national tourism offices were present all weekend.

Now let's celebrate!

Maestra cocinera (master cook) Benedicta Alejo Vargas from San Lorenzo, Michoacán, indubitably the best-known Purépecha cook in the world, is giving a demonstration of the preparation of corundas de siete picos (seven-pointed corundas) while her granddaughter, nearly-four-year-old Imelda, watches.

To the far right of the photo you can see a bundle of oak twigs that are used at the base of the steamer to keep the corundas out of boiling water during the steaming process. In front of maestra Benedicta is a bowl of masa and another bowl of dough balls ready to be wrapped in leaves. To the far left in the photo, that tall object is dried corn leaves, wrapped with a cord for storage. Dried corn leaves are reconstituted for use during the season when fresh leaves are not available.

Corundas, a Purépecha-region specialty, are in this case corn tamales shaped like pyramids, wrapped in long corn leaves (center in the photograph above), and steamed. They can have three, five, or seven points–but popurlar opinion is that maestra Benedicta is the only person capable of consistently making them with seven points!

Maestra Benedicta's corundas con verduras (with vegetables), topped with col de árbol and tzirita. Corundas can be prepared as tontas (corn masa without filling), made with finely chopped vegetables incorporated into the masa (in this case, corn dough) as pictured above, or stuffed with chile strips and cheese.

When I met maestra Benedicta and most of the other traditional cooks, they did not speak Spanish, were shy and retiring, and were generally afraid to speak in public. Today, Benedicta and many of the others are internationally known, speak both Purépecha and near-fluent Spanish. The Encuentro's benefits to these women, most of whom live in distant rural outposts of Michoacán, include the self esteem that comes from being recognized and valued for their enormous contribution to their communities, their state, and their country.

Maestra Benedicta recently told a story of a woman who was standing in the long line at her Encuentro stand. She suggested that the woman buy food from the cocinera at the next stand, saying, "Her food is just like mine. We are making similar things." The woman shook her head. "The other cocinera doesn't speak Spanish." The maestra answered, "But the food speaks for itself."

This small representation of the Virgin Mary, ensconced in a flower-adorned niche at the top of Benedicta's stand, is dressed in typical Purépecha clothing, all made by Benedicta. Notice that her apron is hand-embroidered with typical clay jugs. In 2012, this Virgin traveled to the Vatican with a delegation of artisans and officials from the state of Michoacán, including Benedicta. She and a team of assistants prepared a typical Purépecha dinner for 900 people, including Pope Benedict XVI. Maestra Benedicta was thrilled to cook for her tocayo (namesake). Maestra Benedicta recently laughed as she told a group, "I never thought that I would leave my home in little San Lorenzo, but now–now I feel like a swallow, flying here and there."

Maestra cocinera Juanita Bravo Lázaro from Angahuan, Michoacán gave a fascinating talk about the nixtamal-ization of corn. Among her points were:

- the importance of choosing the very best mazorcas (ears of dried cacahuatzintle corn)

- taking the dried corn from the cob using a lava stone

- processing the corn in a new clay pot that has been freshly cured with cal (builder's lime)

She also elaborated on the use of ceniza (wood ash) and a bit of cal in the corn's cooking water and the carefully watched 20-30 minute time that the corn simmers over a slow wood fire. She emphasized the yellow color that the corn takes on during its cooking and the importance of washing, rinsing, and overnight soaking of the finished nixtamal to remove all traces of both cal and wood ash.

Maestra Juanita mentioned that five liters of prepared nixtamal renders approximately 100 small corundas. In advance of weddings and other important fiestas, townswomen gather and together prepare many hundreds of corundas.

As part of her talk, Maestra Juanita shared some of her experiences in Nairobi, Kenya, during November 2010, when Mexico was a contender for the UNESCO Intangible cultural heritage designation. She talked about how difficult it was for her to leave her home and family and travel halfway around the world to a place she had never seen and had barely heard about. She said, "I hated to leave my family behind. I knew that there would be very few of us Mexicans at the event in Africa, and I knew I would not be able to understand much of the language used there. I was nervous about flying all that distance. But I wanted to be there, in case my country received the prize. So I set aside my fears and took the chance.

"I was standing with a group of people, trying to figure out what the dignitaries were saying–but I couldn't hear much or understand what was going on. Suddenly I heard a huge shout, people were screaming and clapping. 'What? What happened?' I kept asking." Finally someone who spoke Spanish said, 'You won the award! Mexico WON!' And then I felt so proud, so happy to be part of it all. It was a joyous day and I was so happy to be there, representing my town, my state, and my country in Africa."

Next week, we'll continue our exploration and celebration at the XIº Encuentro de Cocineras Tradicionales de Michoacán. There are many stories left to tell and a lot more to enjoy.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.